Continuing our tribute to Clive James , whose new collection A Point of View is The Dabbler Book Club’s current monthly choice (sign up here if you’re not yet a member), renowned internet hoaxer and comedy writer David Waywell explains why Clive, unlike Johann Hari – whose scathing interview with James forms a crucial chapter in the book – is the very best sort of fraudster…

I want to begin by confessing to a shabby trick I once played on Clive James.

It’s a long story, not particularly worth telling, but the essence is that I left an appreciative comment on his website about his book Cultural Amnesia (2007). Only, as was my habit at that time, I linked my comment back to a blog I’d been writing in the guise of a minor TV celebrity. I gave it no thought until some months passed and I received an email from Mr James apparently typed whilst he was riding a greased rodeo pig over a cobbled bridge:

You have to believe tht I never saw your wonderful letter unti now. there was a monumental e-mail fuck-up at this end and everything in the VITAL folder shifted tino orbit around Al;pha Centauri, and has only just returned. It pleases me mightily that you liked my book book. And yes, you shall have your wish. A second volume is already taking shape. In something less that five years it will be here. Meanwhile, thanks again, and I’ll push ahead with the merchandising.

The urge is to fix the typos but they are part of the reply’s charm. That is how it email arrived: rushed, bumbling, wonderful, and not a little shocking. But I was appalled to think that I’d duped him. Even in the deepest depths of my foolishness, I always tried to make it obvious that I was a hoaxer out to provoke laughs and the occasional hard thought. (‘Like any right-minded man of superior intellect and prolific disposable income,’ I had written, ‘I have the complete Sir Clive James oeuvre in hardback, paperback, and, somewhat decadently, I know, covered with the leather ripped from the back of the rare Patagonian snow gibbon.’) How could he mistake this voice for the real thing? Even more worrying was the thought that a second volume might appear in five years with an appreciative note to the minor TV celebrity, who might then feel obliged to dedicate his own book to Clive. Who knew where it all might end?

In reply I compounded my error by demanding proof that Clive was really Clive and not some internet hoaxer pretending to be Clive. Clive, sensibly, didn’t reply. Clive had taught me a valuable lesson: you only get to fool Clive once.

That shame revisited me this week when reading his newest collection of essays, A Point of View, originally written for the radio series of the same name. For those of you with poor reception on the FM, the series provides invited cultural commentators with ten minute slots in which to opine to the educated Radio 4 listenership, or, in my case, a still half-asleep office menial crammed in the belly of a commuter cattle truck rattling into Manchester before dawn on a cold winter’s morning. That’s how I’d first listened to the series after downloading them from the web. I thought I’d heard them all until this book showed me otherwise, for it is in one of the earliest episodes that Clive expresses his deep loathing of all form of hoax, practical joke, and fraud:

In Australia during World War II, a couple of established poets invented the supposedly nonsensical works of fictitious poet called Ern Malley and used them to discredit the modernist pretensions of the young editor who printed them. It never occurred to them that as writers of talent they were not in a position to suppose that they could deliberately write something perfectly meaningless. It probably did occur to them that the success of their venture would entail the ruination of the young editor’s career. They were talented men, but they were also sadistic, a characteristic inseparable from the hoaxer’s personality. (‘Congratulations!’, p. 58).

So there I had it: condemned by the man I’d looked up to ever since I first watched ITV after the watershed and started to wear fawn polyester suits in hot climates. I have the personality of a sadist and, since it hurts me terribly to admit that, probably a masochist too.

But there is a sense that I shouldn’t really care. As Chaplin once said: ‘Cruelty is a basic element in comedy. What appears to be sane is really insane.’ This is certainly something that James has lived by for decades, writing for newspapers, TV, and now the internet. It’s hard to take accusations of sadism seriously from the man who shoved the sharp-clawed Japanese game show Endurance down the front of Britain’s collective underpants in the 1980s.

At the same time, it also highlights the perpetual problem (or is it a virtue?) with Clive James. His is a rambling intellect, treading heavily here, lightly elsewhere. His interests are vast and deep and sometimes shallow. He draws his inspiration from high and low culture. You needn’t look for consistency in James’ writing. You needn’t always think he’s right. What you do embrace is the rolling advance of this ebullient living mind. For proof, you need look no further than his ‘Talking in the Library’ series available on his website – the interview with Martin Amis is worth the price of your birth certificate and has saved my sanity on many a dark day.

As a humourist, James has always been at his best when tackling serious subjects in a light way. As a serious poet, he’s best when stretching for the comic, such as when the anti-Modernist James makes a gesture towards Joyce.

The gesture towards Finnegans Wake was deliberate

And so was my gesture with two fingers.

In America it would have been one finger only

But in Italy I might have employed both arms,

The left hand crossing to the tense right bicep

As my clenched fist jerked swiftly upwards–

The most deliberate of all gestures because most futile,

Defiantly conceding the lost battle.

(A Gesture towards James Joyce)

Clive James was the TV intellectual I listened to (back when puberty kicked in and I first developed an Australian accent). He appeared on our screens as the outsider who had cracked the London establishment. Sure, he’d gone to Cambridge, done the Footlights, but he’d also retained his voice. Occasionally, Anthony Burgess would land on these shores and do every talk show going but, as much as I enjoyed his performances, Burgess never sounded quite right. He’d lost his northern accent – in fact, he seemed desperate to articulate those tobacco-juiced lips of his in an artificially clipped English manner. If Burgess’ pretence was that of depth, James’ was of lightness.

It seems I’m not the only person who felt this way. In the essay that forms the first episode of the second series, James recounts an interview he’d done with a young journalist:

No doubt dragging his school satchel, he turned up at my place expecting to meet the sun-soaked spirit behind the merry columns, programmes and articles that he claimed to have been enjoying ever since he was a child…

But when the article is eventually published, James is shocked at the version of himself he discovers on the page:

…I read on past the second paragraph of this interview and I was suddenly appalled. The encounter had taken place about five years ago and obviously it had depressed him deeply, perhaps permanently. The picture he painted of me was a desperately unhappy and self-questioning paranoid sad-sack. After that it got less funny. (p. 64)

Brutally titled ‘Tea And Tears With An Unfunny Man’, the piece was originally printed in Varsity but republished on the New Statesman’s website here and talks of James’ ‘mumbling pessimism’ and jokes that ‘drip acid’. Its byline belongs to one who would grow up to wear the same long trousers as Johann Hari, the precociously-gifted writer who won the Orwell Prize in 2008 when barely in his thirties. The same committee awarded Clive James a special prize for writing and broadcasting that same year. Only one man still has his Orwell award, since Hari is also the precociously gifted shyster who was forced to return the prize before it was withdrawn, due to such unethical journalistic practices as copious plagiarism and doctoring the Wikipedia entries of those with whom he disagreed, including Cristina Odone, Francis Wheen, Andrew Roberts and Niall Ferguson [see Noseybonk’s take on the Hari scandal here – Ed].

James makes no reference to the subsequent Hari controversy – a shame, especially in light of the most ironic passage of the interview which begins with James talking about journalism:

If I had time, I’d write a little guidebook about what not to do, when handling the press. The press can’t be managed. The only way you can manage the press is to not turn up. You don’t have to answer their questions. This is my first interview in years, and I know you’ll treat me well. But with most people, you should just not answer the question. ‘Are you married, do you have children?’ No, no comment. ‘What do you think of Diana?’ No comment. It’s all you can do. But, even then, your silences will be taken as answers. There’s no way out of it.

Hari concludes:

I must admit that, as a journalist, I felt pretty crap by this point. James had spent ten minutes eloquently explaining why the profession was full of bastards.

One might score a point here by noting that the profession has one less bastard now. But that would be cheap, and it’s perhaps also with a degree of hindsight that I suggest that Hari cuts the man to the material, not the material to the man; making not telling the story, and that in more deft hands the interview could have provided an insightful look at one of our best but most reticent humourists. Few writers of copious volumes of autobiography are quite as reclusive as Clive James. His life is an open book, except that a few of the more interesting pages are glued together. Whatever the truth is about James, one doesn’t approach his memoirs expecting to find it there. Not that I wish to make an argument for more confession or wishing to know details – God knows, there’s already too much being blabbed by celebrity types – but Clive James the entertainer and Clive James the man are two different beasts and, I suspect, the former is less interesting than the latter. And it’s the latter I think we glimpse in Hari’s interview and I see only vaguely in this book.

For James himself, the interview colours the essays that form 2007’s second series. After witnessing the effect of his melancholy on the young interviewer, he insists that he will be more positive. It affords the book the few moments of real self-analysis. In the essay, ‘Clams Are Happy’, James makes a case for choosing happiness over melancholy. Like the other essays in this collection, it is followed by a brief postscript. These are in many ways the most compelling parts of the book. In one essay, James boasts about abandoning smoking, only to confess in the postscript that he started again shortly afterwards. In another, he admits to having been too peevish about bad language in everyday life (cf. the email above). Most of the time, the postscript allows him space to reflect on his argument and judge things anew. The effect soon becomes a familiar pleasure. Polemics can move quite easily into iconoclasm or the overly bombastic rant and though James’ rarely strays that way, these postscripts provide the antidote to any that made too strong a case. Specifically, in the case of ‘Clams Are Happy’, James uses it to obliquely refute Hari’s interview piece:

But quite often melancholy is a medical condition that can be treated with drugs. […] To treat it with admiration is almost always a mistake. An extreme case of that mistake is provided by the case of Sylvia Plath. […] Such misplaced enthusiasm is really a form of triviality, another way of not caring very much about the stricken. (p. 112)

The sentiment is very clear and right: melancholy is not a virtue. However, I’m not sure that the same can be said of that type of negativity and distrust which is elevated just above cynicism and which James has made almost his own. Clive James’ very gift to television was that he was no gift to television: his TV career seemed to end when it started to value polish over the gnarly and objectionable. Professionalism is now so absolute that editors dislike difficult arguments that disrupt their schedule. Experts are silenced when they try to explain a concept which doesn’t fit into the thirty second slot allotted to them. News is no news unless it involves a celebrity name. In such a world, the sins of Johan Hari will become all too frequent. Journalism becomes a business about gloss, superficiality, moral absolutes, brevity, and the snappy headline (e.g. ‘Tea and Tears With an Unhappy Man’)

As he now retrains himself to become a journalist, Hari should look again at James. The reason that James is still cherished by those of us that cherish such things is that he admits doubts, has doubts about his doubts, and even doubts about his certainties. Perhaps there is an element of performance (can anybody be really so shambolic) but if so it’s one of the best out there. On TV, James talked into the camera looking as though his neck couldn’t fit inside his shirt. Sometimes his neck looked like it couldn’t fit inside his neck. Only in words does he move effortlessly.

James himself puts it best, as he often does, when writing in verse. Here he might well be talking about himself:

The falcon wears its erudition lightly

As it angles down towards its master’s glove.

Student of thermals written by the desert,

It scarcely moves a muscle as it rides

A silent avalanche back to the wrist

Where it will stand in wait like a hooded hostage.

(The Falcon Growing Old)

Perhaps Hari’s ear was still too young to be attuned to this ‘student of thermals written by the desert’.

This new collection contains erudition, thought, doubt, contradiction, cynicism, and even melancholy, but these have always been in his work. The angry James is here. So too is that James who can’t work his iPhone, doesn’t understand his computer, stands at odds with so much of the modern world. It’s the same man who replied to a hoaxer pretending to be a minor TV celebrity in a stumbling email typed with his elbows. He also seems almost obsessively preoccupied with wheelie bins and it’s a rare essay that passes without his recourse to mentioning them. His is a precise form of insanity that works through wit, learning, but, most of all, the sheer force of his personality.And in this respect, after sixty essays with postscripts and some three hundred and fifty pages, I began to realise that James personifies the very spirit of the hoaxer. This is not to say that he is anything like Hari but when James was scathing of celebrity culture in that interview, he phrased it in an interesting way:

Celebrity gossip is so out of hand that, if I could possibly do it all again, I’d do it under an assumed name or wearing a mask. The costs are too high.

In the end, the degree to which we know or identify with a writer, celebrity, or artist is governed by how skilfully that person works their art, how casually they wear their mask. Lewis Hyde in his book, Trickster Makes This World, talks about a certain class of being.

Trickster belongs to polytheism or, lacking that, he needs at least a relationship to other powers, to people and institutions and traditions that can manage the odd double attitude of both insisting that their boundaries be respected and recognising that, in the long run, their liveliness depends on having those boundaries regularly disturbed. (P. 13)

Clive James is wrong about hoaxers, though he’s right about fraud. Hari is paying for his actions. James himself, though, remains before us, tricking us, misleading us, and playing us. His mask has become very familiar but, thankfully, he is no longer a celebrity and that mask does slip occasionally. And because it does, Clive James is now a much more interesting creature whilst remaining the best kind of hoaxer there is: one who makes us laugh before fooling us into thinking seriously.

Great stuff. Thanks for such an enjoyably Jamesian essay, David!

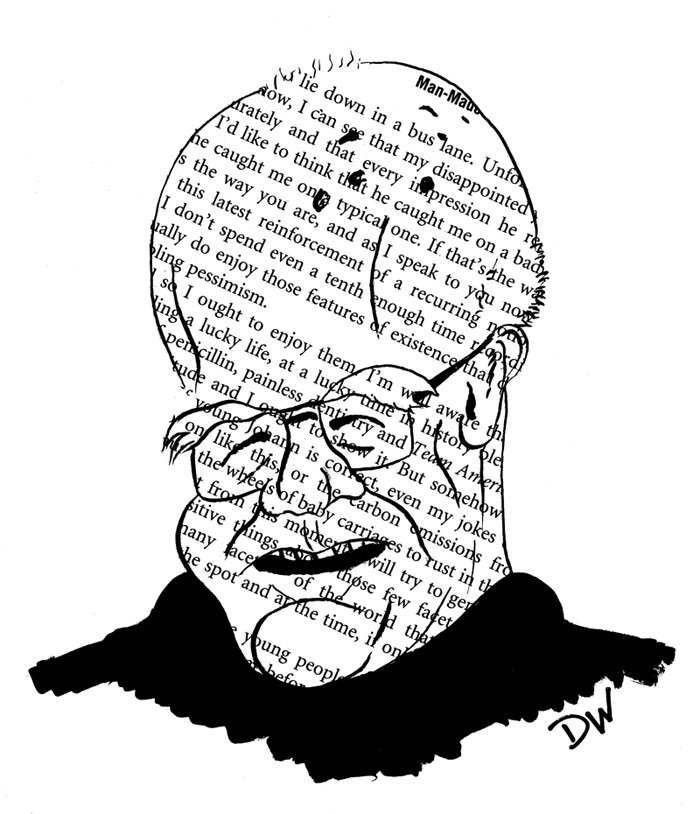

yes I think Jamesian is the word, there’s more than one sentence in there that I imagined being intoned in clive’s nasal singsong. A very nice read to start the day, even the illustration is perfect!

And like David, I do like that Clive James is rather enigmatic, and that there’s the intimation of darker things beneath the avuncular facade

Yes. Several great lines that James would be proud of. I particularly like: “Few writers of copious volumes of autobiography are quite as reclusive as Clive James. His life is an open book, except that a few of the more interesting pages are glued together.”

And the “one less bastard” line on Hari may be ‘cheap’ but it still made me LOL.

Now that is pure James.

I’m a big fan of James. If you’re looking for personal revelations I think you’ll find it in his poetry eg the collection The Opal Sunset, which is very touching about his wife.

I rail against the celebrity culture – what colour knickers Pippa Middleton wears – but then if I am interested in someone (Clive James, Phillip Larkin or whoever) I then find I quite want to hear about what they like for breakfast. (though I don’t want to hear about Larkin’s knickers – grey and baggy, I imagine.)

Yes, I picked that one out. It made me laugh on the bus.

Thank you all for the kind feedback. Reviewing this was fun, though I hadn’t realised I’d written so many Cliveisms. Next time I’ll do the whole thing dressed in a safari suit and hanging off the arm of Elle Macpherson.