Jon Hotten pays tribute to the writing of controversial cricketer-turned-journalist Peter Roebuck, who died after jumping from a hotel window on Saturday…

In front of me is It Never Rains, Peter Roebuck’s diary of his 1983 season with Somerset. It’s waterstained and foxed, the page edges an uneasy shade of yellow on account of it spending a couple of years in the bottom of my cricket bag. It was there because he wrote it around the time I was playing semi-seriously. A while later, another of Roebuck’s books, Tangled Up In White, was in there too, and I used to take plenty of stick for reading them in the dressing room.

Tangled Up In White contained an epic piece about Dean Jones’ 210 in Madras, an innings that Roebuck sketched, unforgettably, through the conditions (a nuclear sun, its microwave heat), fragments of dialogue (Border: ‘quit if you want, we’ll get a Queenslander out here’) and harrowing notes on Jones’ physical and mental deterioration (dry heaves, urinating at the crease, hallucinating in the shower, on a drip at the hospital). It was impossible to read without being stirred for your inconsequential club game, your appointment with the local quicks…

It Never Rains played a wholly different role. It was the first book I’d read that was equivocal about the game, that made it okay to feel ambiguous about something that dominated your life. It was self-aware, knowing, courageous in its way. Roebuck found cricket and his efforts at playing it funny, ridiculous, poignant, hubristic, bathetic in the sense that it switched from the everyday to the unrepeatable, and slightly, darkly heroic, too.

The start of the season is beset by rain, endless and total, that sends him indoors for hours and hours on the bowling machine. Roebuck’s confidence grows and grows until he strides out for his first innings of the year and lasts one ball. As the summer reaches its height, he’s in the grip of a six-week depression that concludes on the first day of August with the simple words, ‘no entry’. It’s a book full of such cadences, the rhythms of real life. There are the identikit ring-roads and fuming pub grub of the touring pro, the grinding tyranny of the fixture list, the recognition of unfathomable talent far out of reach (Botham, Richards and Garner are perched in their corners of the Somerset dressing room), and the comforting quirkiness of any team, anywhere (Colin Dredge, the Demon of Frome; Dasher Denning, the manic opener). Any cricketer will read it and just know.

What I remember most though is the passage where Roebuck hears that he might be considered for England, and realises, down in his heart, that he doesn’t really want to be, or at least that he is profoundly uncertain about it. That admission, and his honesty in revealing it, rounded the game out for me, completed it in my head. This was why it was great – because it was not easy. Somehow, the joy of it was increased by this. Whether you played cricket, wrote about it, thought about it, lived it or watched the odd highlights programme when there was nothing else on, you could never exhaust it. It was, and always would be, too rich, too human and complex, for that.

Roebuck knew it, too. As obituaries often do, his have turned up some tremendous stories. When he went for his interview for Millfield school his parents went as well, and were both offered jobs. According to Wisden, he was just four feet two inches tall when he debuted for Somerset seconds as a thirteen year old. He once wrote a newspaper piece about the decline of Richard Hadlee and then had to bat against him at Trent Bridge – he made a double hundred, that was, the Notts spinner Andy Afford tweeted, ‘scored entirely off his gloves’. Mark Nicholas once sidled up to Roebuck and said that the pair of them were the two best cricket writers around. ‘Who told you that,’ snorted Roebuck, ‘your mother?’

He was an anachronistic man, which probably cost him. He should have lived in the 1950s, not now. Off the field, he had a rock-solid intellectual confidence that enabled him to lead the sacking of Richards and Garner in favour of Martin Crowe – Botham pasted the famous ‘Judas’ sign over his dressing room peg. On it, the same intellect smothered his instinct. Someone described his stooped stance as being ‘like a question mark’. How perfectly appropriate that was.

Roebuck’s ‘conversion’ to being Australian was always amusing; he was the least Australian man on earth, and yet he found acceptance there after his conviction for assault. The great conflicts in his personality, expressed so well in It Never Rains, leaves an ambiguity over his death too. There is a (mostly) unwritten fear over what its circumstances will expose. Yet his books remain fundamentally true – and they remain in my bag, too.

thanks for the interesting write up Jon, your post has galvanised me into finding out more about the man and the Independent tells of a sad and spooky prelude to all this is that 20 years ago Roebuck wrote a foreword to a book on cricketing suicides. He said:

“Cricketers are supposed to be simple, even gung-ho, in sexual matters as in everything else. And yet cricket – and most cricketers – has its dark secrets, its skeletons.” Most poignant of all now is to reflect on Roebuck’s almost triumphant claim in that foreword: “Some people have predicted a gloomy end for this writer,” he wrote of himself. “It will not be so.”

article here

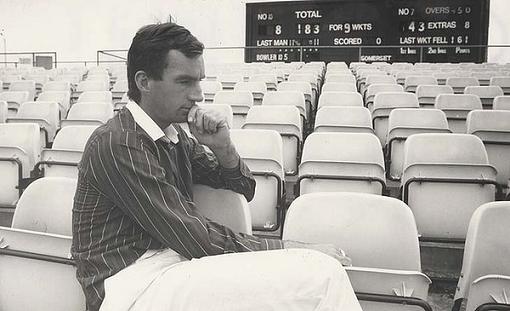

I wonder if the photo of Peter Roebuck was taken with a long lens; the subject unknowingly caught in contemplative mood, or was it a posed shot for inclusion in a book? It seems so apt as a preface to an illuminating piece by one gifted writer on another.

‘What I remember most though is the passage where Roebuck hears that he might be considered for England, and realises, down in his heart, that he doesn’t really want to be, or at least that he is profoundly uncertain about it.’

On the face of it, that is an astonishing admission. Surely, we all, without exception, desperately want to play for England until we realise that the cricketing gods have given us too wide a berth. Was Roebuck’s profound uncertainty borne out of a fear of failure if tested at the highest level? Was the overpowering presence of Botham a factor (having to put up with him at Somerset was probably burden enough)? Did he possess a self-awareness so acute he just knew he wasn’t good enough?

What a corrosive and utterly dispiriting place the Somerset dressing room must have been in the mid 1980s. The atmosphere generated by the egos and negativism of the ‘Mighty Three’ would, no doubt, have flattened a less bloody-minded, determined, intelligent and far-seeing man than Roebuck. It must have taken considerable courage to stand up against the hitherto untouchable arrogance of those truly great players. The story about Hadlee seems to capture the man: ‘state what you believe and then deal with the consequences.’

After reading this post, I went looking for It Never Rains; one Google stopping-off point was a piece written by Roebuck about Botham’s knighthood. It almost took my breath away in its savagery. I wonder if Sir Ian has made any public statements about Roebuck’s tragic demise?

Thanks John and Worm. The book for which Roebuck wrote the forward is David Frith’s Silence Of The Heart – well worth reading.

John do you have a link to the Botham piece – would like to see that myself!

Jon, I seem to be having trouble finding the precise page, but here it is taken from a cricket forum. I trust and hope it is not a hoax:

Roebuck on Botham

A skunk with a moniker is still a skunk.

Elevating Ian Botham to the ranks of the knights of the realm, a promotion he has long sought and for which his lapdogs have long campaigned, merely draws renewed attention to the numerous calumnies attached to his name.

In the light of the the euphoric reaction, it is clear that the time has come to take a closer look at Botham in the round, as man of deeds and misdeeds and not merely a creature of derring-do. It is a thankless task. Decades ago Bill O’Reilly explained his reluctance to tip the bucket on Don Bradman by saying “ the world does not smile on those who spit on statues.”

It is even harder with the Englishman. Botham is relentlessly manipulative and, like most bullies, hunts with a pack.

From the cricketing perspective, Botham’s highest claim to fame is that he inspired his country to many fabulous victories. Closer inspection reveals that with every team he represented, he started brilliantly but eventually became a liability. Along the way he wore the colours of three counties, one State and his supposedly beloved country (an affinity that did not stop him threatening to emigrate to Australia in 1986 or signing a letter of intent to join a rebel tour to South Africa in the apartheid years).

By the end, none of these teams was sorry to see him go. Not that anyone, apart from those who had crossed him, disliked him. Just that he fell into the habit of causing disarray, and dragged teams and emerging players down with him. In his later years Botham worked better as an idea than as a team-mate.

Take England’s record in the 1980s. An impression has been formed that it was a radiant and mostly successful decade for English cricket, and that Botham was largely responsible for this happy state of affairs. In fact, it was an almost unmitigated disaster.

As Scyld Berry demonstrated in a compelling argument presented in a cricket magazine not so long ago, England fared worse in the 1980s than in the 1970s and no better than in the subsequent decade. In short the glory years are a myth. Unchallenged tales told in newspapers about marijuana smoked in dressing-rooms did not help. Nor did the breakaway tours to South Africa that tore the team apart.

Botham began against a distracted Australian team in 1977, made his name against weakened sides in the Packer years, was appointed captain, failed dismally, enjoyed a dramatic and inspiring resurgence after being sacked as captain in 1981 and thereafter waxed and waned.

Nor did the collapse in English cricket that occurred in the 1980s stop with the national team. Drugs and dissolution affected Somerset in the middle years of the decade. Every county indulged in lob bowling, arranged declarations and so forth. Nor were fixed matches unknown.

Of course, Botham was not solely to blame for this deterioration. Too many of us treated the game badly. Nor was he a knight in shining armour. Let us not pretend these things did not happen. It was a dark, unprincipled period and it took England an age to recover.

Despite these reservations, Botham’s record as a cricketer survives all except the most critical scrutiny (he was hurt by relative failures against the mighty West Indians and also by Sir Garfield Sobers’ mixed blessing). He was a wonderful, durable, inexhaustible and entertaining competitor. No match was ever lost till he had been removed.

Alas the all-rounder’s enduring inability to tell fact from fiction is not so easily defended. No reader of his books can rely on them as accurate records of past events. At best they reveal a faulty memory. But, then, truth does not interest him. Image is paramount.

To take one instance of his disregard for demonstrable fact, his loud proclamation that he could not countenance touring South Africa till racial equality had been established does not survive examination. Typically, too, he turned his ultimate withdrawal from the rebel visit into a gesture calculated to advance his popularity and reinforce the notion that Viv Richards was a bosom pal to whom he was unshakably loyal. He said that he could not accept because afterwards he “could not have looked Viv in the eye”.

As might have been expected, Richards himself and David Gower were altogether more impressive. Infuriated by the all-rounder’s hypocrisy, Ali Bacher promptly flourished the letters of intent Botham had signed not long before. Graham Gooch likewise put the record straight in his autobiography. It emerged that Botham had withdrawn from the tour on the advice of his agent.

Nor did supposed nationalism stop Botham making himself unavailable to play in the 1987 World Cup in India. Instead he spent the winter with Queensland, a sojourn that ended in tears after a drunken rampage on a flight to Perth where the final was to be played. Patriotism should be made of sterner stuff.

Not that Botham lacks insularity. He has not hidden his contempt for Australia and Pakistan, and rejected Africa when choosing his charity on the grounds that “people are always starving in Africa”.

He has always lacked judgment. His closest friend in Taunton in the 1980s is languishing in prison after trying to expropriate money from her own father in a property scam. Her husband, another member of Botham’s inner circle, is a despicable little man.

Curiously, Botham told the truth in his solitary appearance as an aggressor in court. Hitherto the law had been used largely as a means of suppressing damaging stories. Then Imran Khan accused him of ignorance and cheating. Unable to imagine any English jury favouring a wealthy Pakistani over a proud and heroic nationalist, and presumably eager to save his tattered reputation, Botham sued. It was a mistake. Opposing counsel pointed out that much worse had been written about without offence being taken, and sought an explanation. None was forthcoming.

It was a relief not to be called as a witness. I have never suspected Botham of cheating, ignorance or even bad sportsmanship. He had too much respect for the game. Alas, he does not maintain the same standards elsewhere.

Enough. Botham’s knighthood is a fait accompli. It was also an inevitability. With its declining culture and absurd aristocracy, England is welcome to him, deserves him. Worse men have been given gongs, including several loathsome editors who danced to Lady Thatcher’s tune. And he has done some fine work for charity raising lots of money, £12 million by his own reckoning.

Swept along by the bonhomie, his chums salute him. Recognising his malice, wary of his populism, his opponents avoid him.

International cricket writer PETER ROEBUCK, who lives in the KZN midlands, was Ian Botham’s county captain at Somerset in the mid-1980s.

Blimey, he really didn’t like Botham.

Brilliant stuff, Jon. There’s a lot more to come out of this, it seems.

(And definite CTOM contender there, John).

Brillaint! Thanks John. I do vaguely remember this now. Def. not a fake. When was Beefy knighted – two years ago? Glad to see Roeby wasn’t nursing any sort of grudge for several decades.

There’s certainly room for a revisionist view of Botham, as there will be many of Roebuck too. There’s some fairly unpleasant stuff on some sites already. But I think this traduces Beefy far too much as a player, and loses real credibility as a result, compulsively readable though it is.

The best para of the above is the one about his ‘close friend’ in Taunton, who’s in prison. What a story must lie behind that… Roebuck obviously didn’t feel confident enough to go full-out for it.

Botham was knighted four years ago (October, 2007)

I agree about the best para, Jon. But I think it was that statement that put a doubt in my mind about the article’s authenticity; Roebuck, uncharacteristically, stopped in his tracks. Perhaps he concluded that he’d already made his position re the knighthood perfectly clear without need to enter a potential minefield; simply opening the gate was enough.

Your comments regarding revision of reputations took me back to an Old Batsman post from February this year when you highlighted the, perhaps, little known tenderness in the relationship between Botham and John Arlott. It came as a welcome surprise to this reader:

http://theoldbatsman.blogspot.com/2011/02/burn-little-brighter-now.html

Blimey was it four years ago? I wonder now whether that piece was ever published over here. Lots of people have mentioned Roebuck’s piece about Ponting in 2008 being his most forceful, but it had nothing on this.

Strange to think of it now, but there was a time when I knew Ian Botham – and rather wished I didn’t. Let me take you back to the early 70s, Yeovil in Somerset. Botham was then 15 or 16, my group of friends about 10 or 11. As his uncle lived just around the corner from us, young Ian was an occasional unwelcome visitor to our road, the future sporting demigod being at that time a mere lout and a bully, albeit one with a loud circle of friends and admirers. Generally, a Botham sighting was enough to send the bravest of us running indoors or jumping headlong into the nearest shrub. Of course, we’d hear people saying that he was good at games – something of a star when it came to the football – but his most visible talent seemed to be for parting younger and smaller boys from their dinner money. Certainly, if anyone had suggested that this guy would end up a Knight of the Realm, honoured by HMQ for services to charity …

As for Botham senior, the uncle, I should perhaps tell you that he was notorious for having a plaque on his gate engraved with the single word ‘BOTHAM’. For some reason this was considered pretentious – it

was the 1970s – and doubly funny because some sort of staining or weathering had blurred the letters so we could almost tell ourselves that it read ‘BOTTOM’. So, walking past his gate, the game was always to shout or say or murmur (depending on level of courage) the word ‘BOTTOM!’ – and hope to hell that Ian was nowhere around.

Of course, it would be quite wrong and foolish to judge anyone at all by their 16-year-old self. But Roebuck’s piece suggests some continuity:

Swept along by the bonhomie, his chums salute him. Recognizing his malice, wary of his populism, his opponents avoid him.

Well, we certainly did. Through all the years of Botham’s fame there was a part of me that always felt, ridiculously, that my IB was the real chap and this other one — the famous, loved, and respected one — some sort of funny impostor. Mentally, I was always shouting BOTTOM. Roebuck’s piece tells me there were others, who knew the man a whole lot better, doing much the same.

I wish you’d warn me if you’re going to write comments that good, JL. They should be posts.

Great story Jonathan – he can’t have been that far off playing for Somerset at that point – at least for the seconds. Think he was only 18 on debut. He probably spent all that dinner money in the bar…