Jonathon Green salutes that great Australian stereotype and master of slang, the ‘larrikin’…

Let us first describe the captain, bottle-shouldered, pale and thin,

For he was the beau-ideal of a Sydney larrikin;

E’en his hat was most suggestive of the city where we live,

With a gallows-tilt that no one, save a larrikin, can give;

And the coat, a little shorter than the writer would desire,

Showed a more or less uncertain portion of his strange attire.H. Lawson ‘The Captain of the Push’ Bulletin 26 March 1892

The larrikin: think Ned Kelly, Shane Warne, or Barry McKenzie. Australian stereotypes. Australian heroes. Variously a hooligan, a rascal, a villain, a Bohemian, and above all one who scorns convention. Most likely comes from the Warwickshire / Worcestershire / Cornish dialect larrikin, a mischievous or frolicsome youth, itself rooted in larking, as in playing around. It turns up in Australia in the 1860s. Drunken, tobacco-spitting, noisy, fighting among themselves, jostling and heckling middle-class passers-by: larrikins represented a threatening invasion of public spaces. Morally panicked, respectable Australia saw these native-born, youthful hooligans as the product of parental laxity, not to mention a throwback to their convict origins. En masse he ran with the push, first recorded in England in 1672 as a press of people or a crowd; its Australian use, as a criminal gang, appears in the 1880s, as does a parallel meaning: a non-criminal crowd or clique.

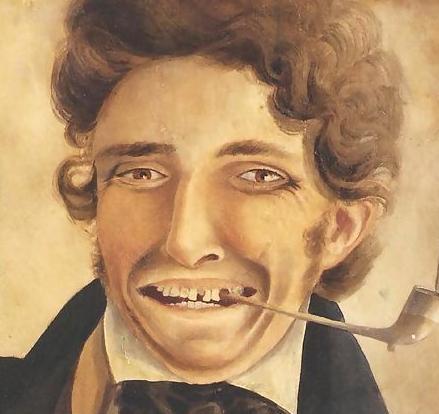

As a youth gang must, they sported a uniform. ‘He wore distinctive high-heeled boots [known as ‘Romeos’] and bell-bottomed trousers. The boots, finely cut and pointed, were handy, so to speak, for putting the boot in; it was also said that there was sometimes a mirror embedded in the toecap, so that, “observation of the mysteries hidden under girls’ skirts might be contrived”. The trousers, flared over the boots, were tight around thighs and bum. The shirt was usually white and collarless, worn sometimes with a vivid neckerchief; the jacket short and loose. The hat was black, round and firm […] And in an age when beards or whiskers were the norm, the larrikin was defiantly clean-shaven. With this appearance went a certain manner, the swaggering walk, the `leery’ look.’* He was accompanied by his girl, the larrikiness, known as his donah or clinah (both borrowed from London costermonger use, as perhaps was the predilection for flared trousers, gaudy neckerchiefs and boots).

They coined some slang, borrowed a lot more; either way they used a good deal. Thus an extract from W.T. Goodge’s ‘Great Australian Slanguage’ (1898):

And his naming of the coinage

Is a mystery to some,

With his ‘quid’ and ‘half-a-caser’

And his ‘deener’ and his ‘scrum’.

And a ‘tin-back’ is a party

Who’s remarkable for luck,

And his food is called his ‘tucker’

Or his ‘panem’ or his ‘chuck’.A policeman is a ‘johnny’

Or a ‘copman’ or a ‘trap’,

And a thing obtained on credit

Is invariably ‘strap’.

A conviction’s known as ‘trouble’,

And a gaol is called a ‘jug’,

And a sharper is a ‘spieler’

And a simpleton’s a ‘tug’.If he hits a man in fighting

That is what he calls a ‘plug’,

If he borrows money from you

He will say he ‘bit your lug.’

And to ‘shake it’ is to steal it,

And to ‘strike it’ is to beg;

And a jest is ‘poking borac’,

And a jester ‘pulls your leg’.

Goodge also hymned ‘The Great Australian Adjective’ (1898), which was bloody and the larrikins definitely used that.

Like the caricatured Cockney costermongers of the London music-hall, ‘larrikin acts’ developed in the 1890s. There were songs such as ‘I’ve Chucked Up the Push for My Donah’ (1893), and ‘The Woolloomooloo Lair’, now categorized as an Australian folksong, and which ran in part:

Oh my name it is McCarty & I’m a rorty party

I’m rough & tough as an old man kangaroo

Some people say I’m crazy, I don’t work because I’m lazy

And I tag along in the boozing throng, the Push from Woolloomooloo.

And when I was just a lad I went straight’way to the bad

A larrikin so hard, you’d strike me blue.

But the government was kind and they didn’t seem to mind

And in Darlinghurst I spent a night or two.

Now the judge gave me a stare and he said, “You’re a lair”

They heaved me into Darlinghurst gaol – you understand.

This was performed by a Londoner, E.J. Lonnen, in 1892; Lonnen dressed the part, and like a number of stage larrikins of the day performed in blackface. Larrikins saw the point: their self-image was as Australia’s blacks: socially marginalised, stereotyped as pursuing ‘black’ i.e. criminal activities, and simultaneously feared and despised.

His fictional evocation emphasised the gentler side: ‘larking’ rather than ‘larceny’. The work of Edward Dyson (Fact’ry ‘Ands, 1906; Benno and Some of the Push, 1911; Spats’ Fact’ry, 1922 ), Louis Stone (Jonah, 1911) and C.J. Dennis (Songs of a Sentimental Bloke, 1915; The Moods of Ginger Mick, 1916) does not completely romanticise him – there can be violence, especially on behalf of a ‘mate’ or of a wronged female – but it ultimately emphasises the positive. Even Dyson’s ‘Chiller Green’, who arrives as a ‘sinister youth’ dressed in the larrkin garb of ‘soft black felt hat […] trousers very skimped in the waist, and high-heeled boots’ and who has ‘eyes full of truculence’ is found a page later to be ‘really a jaunty, companionable youth’. Even if, in a recent set-to he knocked a rival ‘fair off his trolley’ with ‘er half Brunswick’ and ‘got four moon’. And he ends up, in the story ‘The Wooing of Minnie’ thoroughly domesticated and pushing ‘er peramberlater’.

Domesticity seems the fate of every fictional larrikin. Stone’s duo Jonah and Chook transcend the push: one to become rich, the other to marry his larrikiness Pinkey. As for Dennis’s ‘Bloke’, his titulary adjective gives him away. He may have done a stretch inside for ‘stoushin’’ but what really matters is his donah Doreen. And in due course their child. The rabbit-oh Ginger Mick is similarly besotted, beating up ‘a shickered toff’ who ‘slings Rosie goo-goo eyes’; but if he greets the war by questioning Britain’s need for imperial troops, then at the end of the poem cycle he dies ‘a gallant gentleman’, killed in action at Gallipoli and a symbol of many thousands of other working-class Anzacs.

*J. Rickard ‘Lovable Larrikins and Awful Ockers’ in Jrnl. Aus. Studies (1998)

“the product of parental laxity” – from larrikins to hoodies, there’s nothing new under the sun…

Was just going to say a la Brit, that you’d only need to change a few words here and there and this reads almost exactly like a bang up to date description of the whole gangsta rap lifestyle

This made me laugh and triggered off a memory of a bloke I used to work with who’d been in a heavy metal band called Larrikin – their logo was a drawing of a vandalised phone box…

Another fascinating tour, JG.

Intriguing that the ‘stage larrikin performed in blackface’. I wonder how that reflected their attitudes to aborigines? Or was it an African blackface they were adopting? It also makes me wonder how novel it was for later generations of British larrikins to identify – more respectfully, of course – with the blues, soul, hip-hop, etc.

I don’t think they gave a XXXX (first used for beer in Oz in 1878) for the abo. One must recall that blackface minstrelsy had been the most successful form of popular 19th century stage entertainment in the anglophone world since its introduction in the US in the 1820s/30s. I’ve tipped my hat to academic theorising and the larrikins undoubtedly played up their ‘victim of society’ role, but Lonnen may well have been doing no more than what he was used to back in the Old Start.

Thanks. Given the reputation of settler communities I’d guess stage tropes brought from back home would be the overwhelming influence!