In an occasional series Daniel Kalder examines the literary endeavours of the world’s dictators. This week we hear about a dictator who was not only the world’s most feared literary critic but also an unlikely poet of women’s moles and 24-hour taverns.

Perhaps the most famous literary critic of the 20th century, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini (1902-1989) was renowned for his vehement loathing of the work of Salman Rushdie. Indeed, the Ayatollah (or Imam, as he liked to be known) loathed the Satanic Verses so much that he called for Rushdie’s execution. Now Rushdie may seem a bit smug, but I think we can all agree that that was going a bit far. And as a British subject and lapsed Sunni Muslim, Rushdie was not under the Iranian Shia supreme leader’s jurisdiction by any stretch of the imagination. Nor had the Ayatollah actually read the Satanic Verses. No surprise there, of course – ignorance of the offending material is a sine qua non for those who would burn books and kill their authors.

But I digress. Today I am focusing not on the Ayatollah’s critical output, but rather his work as a creative author, which is woefully unknown in the western world, even though he was stupendously prolific (200 of his works are available online). The topics he covered include commentaries on the Qur’an and the Hadith, works on Islamic law, plus multiple tomes on philosophy, gnosticism, poetry, literature and politics. And on top of all that he masterminded one of the epochal events of the 20th century. Not bad – from a Protestant work ethic standpoint, at least.

Prolific output is no sign of quality however, as anyone who has read Khomeini’s fellow dictator Enver Hoxha will attest. But it is difficult for those of us not fluent in Persian to arrive at a judgment on Khomeini’s work as so little of it is available in translation. Indeed, it’s almost as if the authorities in the Islamic Republic don’t want us to read his books, as if they don’t care whether we are converted or not. This is an unusual, even refreshing display of contempt for the lingua franca of the modern world, as almost every other tyrant from Muammar Gaddafi to Islam Karimov of Uzbekistan has revealed his cultural insecurity by having his words rendered into the language of the Great (and little) Satan.

Back to the Ayatollah however, and what is available in English.

• In 1980, Bantam Books published an unauthorised paperback entitled The Little Green Book: Sayings of the Ayatollah Khomeini, hastily compiled in the aftermath of the revolution. This slim volume lifted freely from three separate works by Khomeini: Kingdom of the Learned, Key to Mysteries and The Explanation of Problems. Problems with the text are manifold. The English version was translated from Iranian into French into English, and greatly truncated in the process: 125 pages instead of over 1,000, with a suspicious emphasis on aphorisms about semen, sweat and the anus. To compound matters, it does not attribute specific quotes. And yet in spite of these serious flaws the immensely vengeful, tedious, depressing, obsessive, paranoid, superstitious, reactionary, authoritarian, misogynistic and antisemitic flavour of the Ayatollah’s thought shines through. No wonder many in Iran, forced to submit to one man’s withering interpretation of their cultural and religious inheritance (and that is to say nothing of non-Muslims and unbelievers) are rioting in the streets.

• On the other hand, Islam and Revolution (Mazar, 1981) was compiled by an editor favourably inclined to Khomeini (Hamid Algar, author of the classic Occidentosis: The Plague from the West). I stumbled upon it in the Austin public library and was just about to read the thing when alas, somebody put in a call for it and I had to return it. Optimistically listed as Volume 1, Volume 2 – as far as I can tell – was never published.

• Finally, my desperate quest for more Khomeini led me to this singular, solitary poem, originally published in the New Republic in 1989, just as the Ayatollah was demanding death for Rushdie and poised to take the great leap into eternity himself. This was what I was really interested in – something that would reveal a side of Khomeini unknown to those of us in the west; a more tender aspect of the bearded, reactionary theocrat.

And what a poem! If the first two lines are startling:

I have become imprisoned, O beloved, by the mole on your lip!

I saw your ailing eyes and became ill through love.

Then what follows a few lines down is absolutely amazing:

Open the door of the tavern and let us go there day and night,

For I am sick and tired of the mosque and seminary.

The whole thing ends with a repudiation of Islam in favour of the “tavern’s idol”.

Even allowing for the fact that the Ayatollah is utilising a poetic persona, the poem is remarkable: free thinking, even heretical. And yet … according to Khomeini’s Arabic translator, professor Muhammad Ala al-Din Mansur, of Cairo University, the apparently secular tone is misleading:

Imam Khomeini’s poetry was exclusively a means for the manifestation of his mystical and numinous thoughts while praying to God and reflecting on the mysteries of the creation.

And sure enough, I soon found an essay online in which the critic revealed that everything in the poem is something else, and nothing is what it appears to be. Bummer. But is Khomeini’s stuff any good? According to a pro-regime site:

Imam Khomeini was an outstanding poet and literary figure of Persian language. His prose was elegant and his poetry delicate. He was popular in this respect from the very beginning of his student days in Qum and was known for the soundness of his speech and writings.

But they would say that, wouldn’t they? As for those of us who don’t speak Persian, how are we to judge? Which leads me to a final thought: considering so little of Khomeini’s thought is available in English (even though he established the ideology of a major hegemon in today’s Middle East) – what exactly are all our analysts, specialists and decision-makers consulting when they make pronouncements about the place? I don’t believe for one second that the hacks writing op-eds and the politicians appearing on talk shows speak Persian.

My guess is that they are very often reading interpretations of interpretations, pieces a little like this, albeit longer and written with a note of certainty. And that – frankly – should have us all concerned.

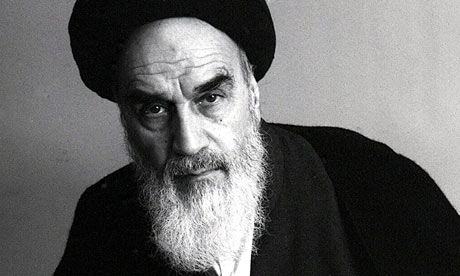

Sorry, another photo enquiry – who captured that amazing portrait above, the face of contempt and egotism?

Yes, he was good at poetry but was he any good at limericks?

there was an Imam from Iran

who opened a bar in Tehran

and after for a bet

installed a minaret

and called time in the style of adhan.

Ian, I wonder if the photographer said something along the lines of: “I want to capture a slightly understated sense of ultimate power; an unspoken statement of intellectual and ideological superiority, combined with a sense of world-weariness and disillusion. So, I want you to picture two things simultaneously: 1) a peanut farmer from Georgia, and 2) the pubs running out of brown ale just as you’re knocking off for the day……”

You know, John, I think it may have been Bailey.

”…loverly, gorgeous, that’s it, one more, adulterous wives? super, just another, homosexuality, fabulous, and another, Wall’s pork sausages, ab-sol-utely fabulous. I think we’ll call it a day.”

Great stuff, Ian. I love the idea of Bailey throwing himself around uttering those words…

Authorative answer from Authorative Answerserver™: Photograph: Denis Cameron/Rex Features – acc. to http://www.tineye.com/search/ef002f52c49278bc0e1ef288ad9a6ffe91af5ae8/ [results expire in 72 hours], and subsequent search in Google Images for Guardian-only instances:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/booksblog/2010/jan/29/dictator-lit-ayatollah-khomeini

So the Ayayollah’s mysterious and numinous thoughts in the 80’s were about the 2005 changes to UK licensing laws? Quite ahead of his time, that Khomeini…

“[I] was just about to read the thing when alas, somebody put in a call for it and I had to return it.”

I used to use that one at school.

Extraordinary. That poem looks like the work of someone cruisin’ for a beheadin’…

(As does Ian’s, in fact…)

Puzzling, the Persians, or Arabs as the yanks once called them and ain’t that food for thought. The Eye-O-Tolley as the Perishers once called him merely carrying on that fine tradition started by the Frogs, toss out the current lot and carry on with the murderous repression yourself raking in the goodies at the same time, not rocket science but hey, works nearly every time.

The great bearded one really hacked off an old acquaintance who had just set up, in Iran, a very tidy facility, making large fibreglass boats and money.

Unfortunately for the Shah.

> sure enough, I soon found an essay online

> in which the critic revealed that everything

> in the poem is something else, and nothing

> is what it appears to be

So Khomeini was something of a Persian Aesop?

Stands to reason, as nothing ever said can be

taken at face value but is subject to constant

(and custom) reinterpretation. What is really

puzzling is that Persians, who collectively can

not be accused of being culturally-backward or

lacking in retrospection, having unseated one

despot for an even worse one, do not apply that

Aesopian principle to supposedly-authoritative

and just religious teachings of the now-deceased

tyrant.

Still, I wish Daniel Kalder would have gone harder

after these “critical” revelations to detect the degree,

if any, of their sycophancy.

This was originally published at the Guardian which has a fairly strict word count & thus limits freedom to head off down alternative routes. However you may assume that when I talk about ‘critical’ revelations I am being quite ironic- they are all extremely sycophantic, except perhaps for some of the stuff by Kho’s Arabic translator which was written from a semi scholarly standpoint about Persian poetic traditions.