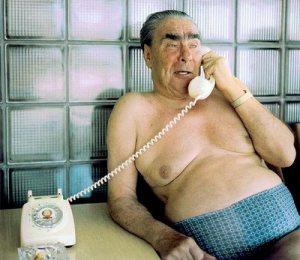

In an occasional series Daniel Kalder examines the literary endeavours of the world’s dictators. This week we remember the lavishly browed and latterly decrepit Leonid Brezhnev, the author of the Soviet Private Ryan.

Master of the USSR in his lifetime, Leonid Brezhnev (1906-1982) is best remembered today for his exceedingly hairy eyebrows and descent into senility while still at the helm of a nuclear superpower. Few indeed are the historians willing to dedicate years of their lives to the biography of a man who didn’t kill nearly enough people to score them a place on the bestseller lists; meanwhile his own memoirs languish entirely unread. But then these three slim, ghostwritten volumes are hardly worth opening – as I discovered when I subjected myself to the first instalment, Malaya Zemlya (Little Land).

Malaya Zemlya tells the story of a hitherto obscure second world war battle in which Brezhnev participated. Brezhnev himself admits that “you will not find Malaya Zemlya – Little Land – in geography books”. Nevertheless, the fighting which took place in this lost corner of Soviet Ukraine was highly significant to the overall war effort, culminating in the “liberation” of Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary and Romania. Or that’s what Brezhnev wants us to believe, anyway.

The book begins much like Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan, minus the exploding skull death porn. As Brezhnev is disembarking from his boat, a bomb sends the future Gensek of the CPSU flying through the air. Fortunately our hero survives, and promptly embarks on the vital wartime work of, well, talking a lot.

Allow me to explain. As a political officer, Brezhnev’s role was not to risk his life in battle but rather to produce and disseminate propaganda, enforce political correctness and keep a close eye on dubious types, although that last aspect of his work is never mentioned in Malaya Zemlya. Instead we get lots of admiring accounts of the “mass heroism” of the Soviet people, designed to both commemorate the fallen and glorify the regime he embodied. Thus we learn of Maria Pedenko who “spared neither her youth nor her own life”, and also of the unnamed soldier who refused to accept his leave, insisting instead that he rejoin his beloved unit at the front.

Alas, in Brezhnev’s hands these potentially gripping stories are reduced to bathetic agitprop. An intriguing subtext of anxiety does emerge from beneath the layers of propaganda, however. Clearly feeling the need to justify his non-combatant role, Brezhnev repeatedly alerts us to important speeches he made, quotes his own pamphlets approvingly, and stresses how eager the generals were to hear and act upon his advice. Indeed, without Brezhnev the war might well have been lost, for ultimately “the political workers became the heart and soul of the armed forces”.

And yet there are still a few small details which leap out at the reader, odd sentences or anecdotes which don’t quite fit or have acquired an unintentional humour with the passage of time. It’s hard not to enjoy an ironic chuckle when Brezhnev delivers his take on the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. Apparently it wasn’t a cynical ploy by Stalin to split Europe with Hitler, but rather a move which gave the Soviets “time to strengthen the country’s defence capacity”. Although Brezhnev does admit that “not everybody appreciated this”.

Perhaps it is what’s missing from the narrative which leaves the biggest impression. Aside from a brief mention early on, Stalin is entirely absent, although I understand he was an important figure in the USSR at the time. Nor is there any mention of the terror tactics the Red Army used against its own troops, or the campaign of rape which was unleashed upon Europe’s women as the eastern half of the continent was “liberated”. (For an honest and yet respectful take on the Red Army under Stalin, read Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate).

The most striking absence, though, is the narrator’s own body. As Brezhnev did not participate in the fighting, he is almost always an observer, a phantasmagorical voyeur untouched by the war, commenting on the deeds of others. In fact, after that opening scene in which he is sent flying, the Brezhnev ectoplasm only becomes corporeal twice: while fleeing from a falling explosive (he was the one to detect its approach, of course) and when confronted by an advancing horde of Germans. At last Brezhnev locates his hands and seizes a machine gun, opening fire. However, this moment of action comes to a swift conclusion when real soldiers arrive in the trench. “One of them touched my arm,” says Brezhnev. “Let a machine-gunner take over, comrade colonel,” he is told.

I found this scene curiously affecting. I could see the battle-hardened Soviet soldier watching the pompous propagandist playing at being the warrior, and then gently intervening as if to say “there there, give it to me, hairy eyebrows. I’ll kill the fascists for you.”

The young Brezhnev had wanted to be an actor. Decades later he liked to surprise his Politburo colleagues by spontaneously quoting Yesenin and Merezhkovsky, poets banned by Stalin. Thus when Malaya Zemlya and its sequels Rebirth and Virgin Lands were published to unanimous acclaim in 1978, the Gensek’s frustrated creative desires were at last satisfied, even though he wasn’t the real author. Millions of copies were printed, there was a movie adaptation, an epic painting was hung in the Tretyakov, and Brezhnev was not only granted membership of the Soviet writers’ union (card number one, no less) but awarded the Lenin prize. Azeri pop singer Muslim Magomayev even recorded this awesome track.

Cynics might say this was merely the usual flattery accorded to a Soviet leader by the fawning sycophants in his court – and those cynics can rest easy, because 30 years later nobody cares. In fact, preparing to write this blog, I contacted a friend in Russia, a member of the last generation to be educated in the Soviet school system, for his thoughts on Brezhnev’s masterpiece. This is what he told me: “I don’t even know what you’re talking about.”

curiously riveting, and actually sounds less bonkers than the previous 2 reviews – as I was only 4 when he died, all I know about Brezhnev is that he had funny eyebrows and was subject of a film with Margi Clarke that involved a lot of smoking, swearing and having sex with sailors.

You could have spared us the photo. How did you find it? Googling “Brezhnev Nude”? Not a common search term, methinks.

I did a Soviet Politics course at university – I think they’re called modules now – whilst Comrade Leonid was still GSCPU and even then there wasn’t enough of interest in or about him to furnish more than ten minutes of a tutorial.

To complement Brezhnev’s general lack of historical visibility, there aren’t many decent shots of him online – apart from this one, of course.

My guess is that like many politicians he was seeking to convey an impression of dynamism and modernity. Those trunks were surely constructed using the very latest super-sleek nylon.

interesting to note that according to wikipedia: “In an opinion poll by VTsIOM in 2007 the majority of Russians wanted to live during the Brezhnev’s era rather than any other period of Soviet-Russian history during the 20th century”

Watching the dear leader propped up between two Kremlin heavies, like a suited Schroedinger’s moggie, he may have been deceased there again not, reminded me of Murphy’s corpse in Spike Milligan’s Puckoon, taken to the photographers for a passport photo, so he could be buried in the churchyard, separated from the church during partitioning. “He doesn’t look well” said the snapper.

Wasn’t Brezhnev a bit of a petrol head with a collection of motors rivalling Jay Leno? It must be said however, the angel Gabriel compared with old Soso Djugashvili, Trainee priest, choirboy, poet, one time Rothschild employee, hammer of the Okhrana and all round bloodthirsty murdering psychopath.

Brezhnev’s era was a bit of a golden age for many folk in the USSR, stagnation or not. As Malty points out, he wasn’t much of a butcher, and he provided shitty consumer goods, cheesy films, crappy apartments to the masses… all of which were better than almost everything they had seen before. Even the Yurts in the Turkmen desert got electricity.