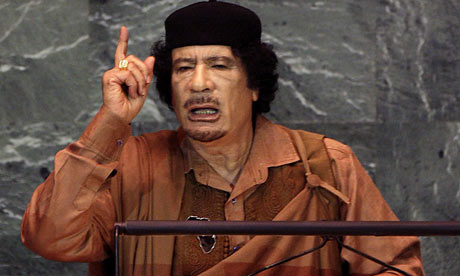

In an occasional series Daniel Kalder examines the literary endeavours of the world’s dictators. First, a topical look at the oeuvre of Muammar Gadaffi of Libya.

A mumbling, murderous, Ukrainian nurse-fondling tyrant he may be, but – even as American bombs rain down from on high – you’ve got to hand it to Muammar Gaddafi: the man has staying power. Born in 1942, he led the coup against the Libyan monarchy in 1969 – the same year Sesame Street debuted on US television. He’s as old as ineffably boring Sir Paul McCartney, his regime as venerable as Big Bird. And, like many dictators, he fancies himself as a writer.

Gaddafi’s most famous literary work is The Green Book, published in 1975. This treatise on “Islamic socialism” defined the concept of Jamahiriya, a state without parties that would be governed directly by its people. Which, in practice, translates as a military dictatorship, headed by – you guessed it – Gaddafi! His subsequent volume, Escape to Hell, is less well known. Marketed in the UK as a single collection of short stories and essays, it is in fact an amalgamation of two books: Escape to Hell (1993) and Illegal Publications (1995). Of course, while it’s safe to say that all works of dictator literature are to some extent fictional, few tyrants have tackled the art of Chekhov and Maupassant. I was quite excited to see how the colonel fared.

One of the first things I learned is that Gaddafi has little grasp of literary classifications. The texts in Escape to Hell are, alas, not short stories but rambling prose feuilletons. There are no characters, no twists, no subtle illuminations; indeed, there is precious little narrative. Instead, you get surreal rants and bizarre streams of consciousness obviously unmolested by the hand of any editor.

One of Gaddafi’s major themes is hatred of the city, which he views as a monster that alienates, isolates, crushes the spirit, separates man from God and so on:

This is the city: a mill that grinds down its inhabitants, a nightmare to its builders. It forces you to change your appearance and replace your values; you take on an urban personality, which has no colour or taste to it… The city forces you to hear the sounds of others whom you are not addressing. You are forced to inhale their very breaths… Children are worse off than adults. They move from darkness to darkness… Houses are not homes – they are holes and caves…

Gaddafi is a Bedouin, opting to live in a tent under the desert sky rather than in a palace, so to some degree his horror of city life is understandable. But he’s surely laying it on a bit thick here:

Yesterday a young boy was run over in that street, where he was playing. Last year a speeding vehicle hit a little girl crossing the street, tearing her body apart. They gathered up her limbs in her mother’s dress. Another child was kidnapped by professional criminals. After a few days, they released her in front of her home, after they had stolen one of her kidneys! Another boy was put into a cardboard box by the neighbourhood boys in a game, but was run over accidentally by a car.

Apparently, city folk also watch cockfights and football, both of which are bad. The village is far superior: a place where “physical labour has meaning, necessity, usefulness, and is a pleasure besides. There, life is social, and human; families and tribes are close. There is stability and belief. Everyone loves one another…” etc, ad nauseam.

Slightly more interesting (and almost a story) is Suicide of the Astronaut, in which a man visits the moon, finds nothing, and upon his return to earth discovers that his qualifications as a space explorer leave him, like an arts grad, unable to secure useful work. He commits suicide. Thus, Gaddafi seems to be stating that space exploration is, well, a load of bollocks. In the title story – a truly unhinged free-form eruption of useless words – Gaddafi declares that it was an “Arab prince”, not Columbus, who discovered America. The rest is incoherent blather. In Death, he tackles the pressing question: is death a man, and thus to be fought, or a woman to whose tender embrace we must surrender? I won’t ruin the ending for you.

Yet, while Escape to Hell is undeniably awful, it is not uniformly so. Gaddafi has a real gift for invective: he can spew with the best of them. He can also do sarcasm, and there are several entertaining passages in which he ridicules the obscurantism of Islamists (“How can we move ahead, while we still do not know… Was the camel of Ali, may God preserve him, white or brown? Was Othman’s shirt made of cotton or nylon?… Should a beard be dyed with henna or shampoo?!”). In fact, Gaddafi himself likes to load his prose with allusions to the Qu’ran, even though he has frequently been quite “liberal” in his interpretation of Islam. In the 1970s, for example, he openly denigrated Mohammed, and even funded an American Jesus sect, the “Children of God” – who, in turn, venerated him as a messianic figure.

In his foreword to Escape to Hell, Pierre Salinger, a former JFK aide and the chief proponent of the theory that it was Iran and not Libya who carried out the Lockerbie bombing, argues that by reading Gaddafi’s thought we shall come to a better understanding of the man, thereby seeing past the crude, scary construct of the western media. He’s correct, of course – and what we find is a mind that cannot follow a coherent thought for very long, is filled with crude dichotomies and nonsense, and rambles along at random, collapsing in on itself before exploding outwards again in a burst of surreal gibberish.

And speaking of exploding, whatever happens to Gaddafi in the next few weeks, one thing is certain: his demise won’t be much of a loss to the world of literature.

That first excerpt reads like something you might find in Resurgence magazine.

”like many dictators, he fancies himself as a writer.”

hee, hee.

He demonstrates again that one should be very wary of people who insist that everyone should live a good and simple life – especially if they’re armed.

…and power-crazed psychopaths too, of course.

It’s a lonely profession you know, dictatoring, not everyone is up to the job, needs fortitude. Little wonder the old lad sat down and penned, out there in the sand, in his teepee or whatever, those buxom burds lying on guard, shifty bunch of camel drivers outside, plotting a coup every other Thursday, Texas tea glugging out of the wadi just a few yards away.

What I object to is the shite dress sense, I mean, have you seen the jalaba?. Not just batty daffi of course, remember Mao, or Joe, like workers playtime. Not so onkel Addie of course, I well remember that summer evening at Beyreuth, tan duster coat, brown jackboots, white shirt and black tie, now he had dress sense, although rumour has it that it was all for Winnie W.

It was Lohengrin that night by the way, that wally Julius came wearing a swan outfit, all the same that mob from the press.

malty, your comments are mini masterpieces!

Thank you Daniel, for reading so bravely, so that we may not have to!

Is the spaceman thing supposed to be an allegory that it doesn’t pay to think above your station, don’t try to reach too far, just stay in your tent and listen to what Uncle Muammar tells you..? Or maybe it really is just bonkers nonsense

That bit about the Arab Columbus reminds me of Gadaffi’s contribution to Shakespearean studies, more particularly the Authorship Question: he claims somewhere that the Bard was an Arab, a certain Sheikh Speare …

I must say, the one about the astronaut sounds pretty good…

Worm & Brit: the Death of the Astronaut is indeed an allegory of sorts, and probably the most coherent narrative in the book. Col Q. is ridiculing the exploration of space when man has much more important things to do on earth, a full life to live etc, although he doesn’t directly specify obeying him as one of those important things. It’s quite short and is almost readable. From an inter-textual point of view, JG Ballard had much the same take on space travel.

Jonathan: The bit about Columbus flies out of nowhere and then disappears again, like many of Col. Q’s thoughts in the book.

Worm: trust me, Col. Q is a page turner in comparison to some of the dictator prose I have endured. The fact that he’s bat poop crazy makes the experience somewhat unpredictable.

Talentless guys who fancy themselves artists become dictators so they will have a (literally) captive audience. Nero made the Roman public listen to his music, Mao had everyone reading his little red book, Hitler bored everyone with his table talk which was mostly half-baked philosophy. Saddam Hussein used to write plays which were put on at Baghdad and Mussolini wrote romantic novels.

Does anyone read Mary Renault? The Mask of Apollo featured Dionysius of Syracuse, a tyrant who like Gadaffi owed his power to mercenaries. He wrote plays that were put at the Athenian festivals.

“He was fond of having literary men about him, such as the historian Philistus, the poet Philoxenus, and the philosopher Plato, but treated them in a most arbitrary manner. Once he had Philoxenus arrested and sent to the quarries for voicing a bad opinion about his poetry. A few days later, he released Philoxenus because of his friends’ requests, and brought the poet before him for another poetry reading. Dionysius read his own work and the audience applauded. When he asked Philoxenus how he liked it, the poet replied only “take me back to the quarries”.”