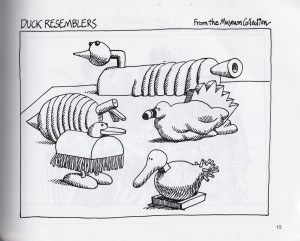

Via Stan Madeley I discover this marvellous cartoon by Kliban.

The world can be divided into two types of people: those who like to divide the world into two types of people and those who don’t. I firmly belong in the latter camp, but nonetheless the world can be divided into two types of people: those who ‘get’ the above cartoon and those who think they’re missing something.

Instantly upon seeing the cartoon I was reminded of my favourite joke, which is about a man who has an orange instead of a head. I once told this joke to a colleague and he got so angry about the punchline that I thought fisticuffs might be in the offing. He probably wouldn’t like Waiting for Godot. Anyway here’s the joke. Enjoy!

Chap is walking down a street when he sees a man with an orange instead of a head. So he says: “Excuse me, I can’t help noticing that you have an orange instead of a head. How did that happen?”

Man with an orange instead of a head says: “Ah, it’s a long story. One day I was on the beach when I found an old lamp. I gave it a rub and out popped a genie who gave me three wishes.”

“That sounds great, but why do you have an orange instead of a head?”

“Well what happened was, for my first wish, I wished I was the world’s richest man… and POOF! suddenly tons of cash and gold everywhere.”

“Brilliant. So why do you have an orange instead of a head?”

“Well for my second wish, I wished I had the world’s most beautiful woman as my girlfriend… and POOF! There she was, a stunner.”

“Okay, great… but why do you have an orange instead of a head?”

“Ah,” said the man. “For my third wish I wished I had an orange instead of a head.”

ENDS

Arf arf!

Pure, unadulterated Wheel tappers and Shunters, laff, I nearly took the offer of a job.

binary gags, who’d have thought?

1: 1010010 101 1 111 1

0: 111 1?

1: 111 1 1011101 1001101 111 10 1 1100000111100111101 100001 11101 111101

0: 111 10?

1 : 110001110 11 10001 111100111 11111 10 1100 101011111 111 10111111 100111111 1

0: 111 100 101?

1: 3

Ian:

1010011 !!!!

Is this the longest joke, or indeed if joke it be?

Metterlings list (NB, not the schmetterling list)

List No. 1

6 prs. shorts

4 undershirts

6 prs. blue socks

4 blue shirts

2 white shirts

6 handkerchiefs

No starch

serves as a perfect, near-total introduction to this troubled genius, known to his contemporaries as the “Prague Weirdo.” The list was dashed off while Metterling was writing Confessions of a Monstrous Cheese, that work of stunning philosophi- cal import in which he proved not only that Kant was wrong about the universe but that he never picked up a check. Metterling’s dislike of starch is typical of the period, and when this particular bundle came back too stiff Metterling became moody and depressed. His landlady, Frau Weiser, reported to friends that “Herr Metterling keeps to his room for days, weeping over the fact that they have starched his shorts.” Of course, Breuer has already pointed out the relation between stiff underwear and Metterling’s constant feeling that he was being whispered about by men with jowls (Metterling: Paranoid-Depressive Psychosis and the Early Lists, Zeiss Press). This theme of a failure to follow instructions appears in Metterling’s only play, Asthma, when Needleman brings the cursed tennis ball to Valhalla by mistake.

The obvious enigma of the second list

List No. 2

7 prs. shorts

5 undershirts

7 prs. black socks

6 blue shirts

6 handkerchiefs

No Starch

is the seven pairs of black socks, since it has been long known that Metterling was deeply fond of blue. Indeed, for years the mention of any other color would send him into a rage, and he once pushed Rilke down into some honey because the poet said he preferred brown-eyed women. According to Anna Freud (“Metterling’s Socks as an Expression of the Phallic Mother,” Journal of Psychoanalysis, Nov., 1935), his sudden shift to the more sombre legwear is related to his unhappiness over the “Bayreuth Incident.” It was there, during the first act of Tristan, that he sneezed, blowing the toupee off one of the opera’s wealthiest patrons. The audience became convulsed, but Wagner defended him with his now classic remark “Everybody sneezes.” At this, Cosima Wagner burst into tears and accused Metterling of sabotaging her husband’s work.

That Metterling had designs on Cosima Wagner is undoubtedly true, and we know he took her hand once in Leipzig and again, four years later, in the Ruhr Valley. In Danzig, he referred to her tibia obliquely during a rainstorm, and she thought it best not to see him again. Returning to his home in a state of exhaustion, Metterling wrote Thoughts of a Chicken, and dedicated the original manuscript to the Wagners. When they used it to prop up the short leg of a kitchen table, Metterling became sullen and switched to dark socks. His housekeeper pleaded with him to retain his beloved blue or at least to try brown, but Metterling cursed her, saying, “Slut! And why not Ar- gyles, eh?”

In the third list

List No. 3

6 handkerchiefs

5 undershirts

8 prs. socks

3 bedsheets

2 pillowcases

linens are mentioned for the first time: Metterling had a great fondness for linens, particularly pillowcases, which he and his sister, as children, used to put over their heads while playing ghosts, until one day he fell into a rock quarry. Metterling liked to sleep on fresh linen, and so do his fictional creations. Horst Wasserman, the impotent locksmith in Filet of Herring, kills for a change of sheets, and Jenny, in The Shepherd’s Finger, is willing to go to bed with Klineman (whom she hates for rubbing butter on her mother) “if it means lying between soft sheets.” It is a tragedy that the laundry never did the linens to Metterling’s satisfaction, but to contend, as Pfaltz has done, that his consternation over it prevented him from finishing Whither Thou Goest, Cretin is absurd. Metterling enjoyed the luxury of sending his sheets out, but he was not dependent on it.

What prevented Metterling from finishing his long-planned book of poetry was an abortive romance, which figures in the “Famous Fourth” list:

List No. 4

7 prs. shorts

6 handkerchiefs

6 undershirts

7 prs. black socks

No Starch

Special One-Day Service

In 1884, Metterling met Lou Andreas-Salomé, and suddenly, we learn, he required that his laundry be done fresh daily. Actually, the two were introduced by Nietzsche, who told Lou that Metterling was either a genius or an idiot and to see if she could guess which. At that time, the special one-day service was becoming quite popular on the Continent, particularly with intellectuals, and the innovation was welcomed by Metterling. For one thing, it was prompt, and Metterling loved promptness. He was always showing up for appointments early—sometimes several days early, so that he would have to be put up in a guest room. Lou also loved fresh shipments of laundry every day. She was like a little child in her joy, often taking Metterling for walks in the woods and there unwrapping the latest bundle. She loved his undershirts and handkerchiefs, but most of all she worshipped his shorts. She wrote Nietzsche that Metterling’s shorts were the most sublime thing she had ever encountered, including Thus Spake Zarathustra. Nietzsche acted like a gentleman about it, but he was always jealous of Metterling’s underwear and told close friends he found it “Hegelian in the extreme.” Lou Salomé and Metterling parted company after the Great Treacle Famine of 1886, and while Metterling forgave Lou, she always said of him that “his mind had hospital corners.”

The fifth list

List No. 5

6 undershirts

6 shorts

6 handkerchiefs

has always puzzled scholars, principally because of the total absence of socks. (Indeed, Thomas Mann, writing years later, became so engrossed with the problem he wrote an entire play about it, The Hosiery of Moses, which he accidentally dropped down a grating.) Why did this literary giant suddenly strike socks from his weekly list? Not, as some scholars say, as a sign of his oncoming madness, although Metterling had by now adopted certain odd behavior traits. For one thing, he believed that he was either being followed or was following somebody. He told close friends of a government plot to steal his chin, and once, on holiday in Jena, he could not say anything but the word “eggplant” for four straight days. Still, these seizures were sporadic and do not account for the missing socks. Nor does his emulation of Kafka, who for a brief period of his life stopped wearing socks, out of guilt. But Eisenbud assures us that Metterling continued to wear socks. He merely stopped sending them to the laundry! And why? Because at this time in his life he acquired a new housekeeper, Frau Milner, who consented to do his socks by hand—a gesture that so moved Metterling that he left the woman his entire fortune, which consisted of a black hat and some tobacco. She also appears as Hilda in his comic allegory, Mother Brandt’s Ichor.

Obviously, Metterling’s personality had begun to fragment by 1894, if we can deduce anything from the sixth list:

List No. 6

25 handkerchiefs

1 undershirt

5 shorts

1 sock

and it is not surprising to learn that it was at this time he entered analysis with Freud. He had met Freud years before in Vienna, when they both attended a production of Oedipus, from which Freud had to be carried out in a cold sweat. Their sessions were stormy, if we are to believe Freud’s notes, and Metterling was hostile. He once threatened to starch Freud’s beard and often said he reminded him of his laundryman. Gradually, Metterling’s unusual relationship with his father came out. (Students of Metterling are already familiar with his father, a petty official who would frequently ridicule Metterling by comparing him to a wurst.) Freud writes of a key dream Metterling described to him:

I am at a dinner party with some friends when suddenly a man walks in with a bowl of soup on a leash. He accuses my underwear of treason, and when a lady defends me her forehead falls off. I find this amusing in the dream, and laugh. Soon everyone is laughing except my laundryman, who seems stern and sits there putting porridge in his ears. My father enters, grabs the lady’s forehead, and runs away with it. He races to a public square, yelling, “At last! At last! A forehead of my own! Now I won’t have to rely on that stupid son of mine.” This depresses me in the dream, and I am seized with an urge to kiss the Burgomaster’s laundry. (Here the patient weeps and forgets the remainder of the dream.)

With insights gained from this dream, Freud was able to help Metterling, and the two became quite friendly outside of analysis, although Freud would never let Metterling get behind him.

Apologies to Woody

Hmmm. I feel a blog redesign coming on.

I’d have liked to have seen Victor Borge do this material.