Diary of a Nobody is a fictional account of the daily life of Mr Charles Pooter, a middle-aged City of London clerk. It was written by George Grossmith and illustrated by his brother Weedon in the late-1880s and was originally serialised in Punch. It’s available in book form, unused and unsullied, for one pence.

It’s a comedy about the Little Man. Just like a great many of us, Mr Pooter is a Nobody who feels he deserves to be a Somebody. He writes in the frontispiece:

Why should I not publish my diary? I have often seen reminiscences of people I have never even heard of, and I fail to see – because I do not happen to be a ’Somebody’ – why my diary should not be interesting. My only regret is that I did not commence it when I was a youth.

Charles Pooter

The Laurels,

Brickfield Terrace

Holloway.

It’s a very funny book. Rarely has irony been more delicately and devastatingly deployed, usually to show up the distance between Mr Pooter’s position and his aspiration, between his self-regard and how he’s regarded by others (in the quotation above we find him straining on the social leash with his characteristic minor-key desperation, the over-assertiveness of that final full-stop providing a particularly pathetic touch).

But it’s a more balanced and involving portrait than one that merely mocks. We often see him in a light that elicits a great deal of sympathy; his love of family and home, for instance, is genuine and touching. Nor is Mr Pooter a man without honour or integrity (though these qualities do tend to come under some strain).

Worth reading, then, just for its engaging balance of mocking and affectionate humour. However, the more I’ve thought about the novel, the more I’ve been struck by how contemporary are its preoccupations. It marks the opening up of a subject that has proved perennially fascinating to writers and audiences alike: the plight of the Little Man trying to negotiate the lower but no less treacherous slopes of a complicated industrialised society.

Perhaps predictably – given his talent for unearthing the remarkable and true from under the weight of contemporary condescension – Orwell was a fan, reckoning the novel’s popularity in Russia was owed to its reading like Chekhov in translation. Perhaps less arguably he hailed it as:

…a very good book to read if you wanted to get a picture of English life, even though it was written in the 1880s and has an intensely strong smell of that period. Charles Pooter is a true Englishman both in his native gentleness and his impenetrable stupidity.

I’d say that Grossmith’s ‘picture of English life’ with its ‘true Englishman’ ended up markedly influencing a couple of Orwell’s early, inter-war novels. The latter’s treatment of leading characters in Keep the Aspidistra Flying and Coming up for Air, is similar to Grossmith’s (whilst being less directed at humour and having a harder edge): finely-balanced irony is deployed in order to achieve a mockery that doesn’t exclude sympathy. The trials of Mr Pooter echo through them, but with more bitterness and bereft of much of the accompanying laughter.

These two novels also inhabit a similar atmosphere to that in which Pooter swam: the protagonists are precarious in their status, desperate to maintain their self-respect whilst teetering on the edge of a some form of grimy, pinched, hole-and-corner fate (the last, a favourite Orwell description of humiliating obscurity). Again, Pooter’s balancing act is played for laughs – Orwell’s characters’, much less so.

Orwell ratchets the off-white-collar dystopia a great many notches further in Nineteen Eighty-Four: Mr Pooter’s horrific fate is to re-emerge as Winston Smith. Smith is the Last Man (from Orwell’s alternative title for his novel) but he’s also the Little Man, an obscure, minor functionary with ordinary aspirations and ordinary appetites – which, of course, doom him. A thought experiment renaming Nineteen Eighty-Four as Diary of a Nobody isn’t a stretch – it’s just this time the title points to futuristic tragedy rather than contemporary comedy. As Orwell came to recognise, the world can contain things worse than ‘capitalism’ with its competition and disorder. In fact, tracing poor Winston Smith back to the gently stupid Charles Pooter makes Orwell’s vision even more terrifying…

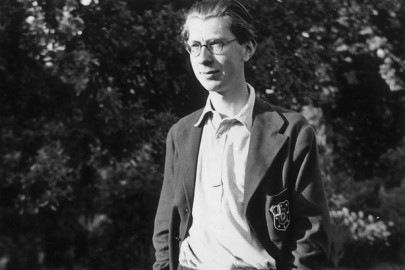

Moving on a few post-war years, doesn’t Mr Pooter’s son, Lupin (both are pictured above), find his echo in the works of the so-called Angry Young Men of the 1950s? The deliciously-self-named Lupin is a young man who can’t quite decide whether to be go-ahead or decadent. But in any event, he sets out to rebel against the confined view of the world held by his father, causing him much trouble and embarrassment in the process. His chasing after a succession of the less respectable fashions (he would have enjoyed jazz in the later era), his volatile combination of gullibility and disillusionment, of uncertainty and conviction, make him something of a model for the sort of revolting youth first spotted in numbers during the ’50s. He’s an early form of overgrown teenager. Lupin Pooter to Jimmy Porter: perhaps all that sits between the two is the cynicism that descended in the wake of a World War or two…

Spying another thread, I won’t follow too far the parallels between Diary of a Nobody and the English sitcom as we could be here all day. The latter’s middle-class landscapes are thickly populated by Pooters, jostling, blundering and prat-falling. I’ll just mention two: first, Richard Briers’ superb portrayal of a cul-de-sac Pooter in the much underrated Ever Decreasing Circles, an interesting and gently amusing reworking of Grossmith’s themes; second, The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin, wherein the hero Reggie finds himself in the midst of a sort of nervous breakdown, one produced by a schizophrenic tension between what might be described as his inner Charles and his inner Lupin – he’s eventually driven completely off the rails of respectability, his inner Lupin emerging triumphant.

The genius of Diary of a Nobody, then, lies in more than its humour. It’s not just an amusing account of the goings-on of the residents of The Laurels, Brickfield Terrace, Holloway; it has some universal application, and not just within the pages of literature.

It’s been said (here, as it happens) that the humour in Diary of a Nobody is simply cruel. But surely the reader isn’t expected to laugh unreflectively? We’re all Mr Pooters, at least those of us who aspire to some form of worldly recognition, however modest, however exalted. When we point at him, we’re pointing into a mirror. When we laugh at him, we’re laughing at ourselves, and especially at our social pretensions. And this turns out to be quite liberating. We should conclude that it’s best not take this absurd rigmarole too seriously.

One also mustn’t forget the happy ending: in Chapter: The Last we leave Mr Pooter secure in his domestic bliss and, for the moment at least, reconciled with the contumacious Lupin. To adapt Orwell, Mr Pooter keeps his aspidistra flying. A satisfying end and one that, perhaps unexpectedly, helps reconcile us to the nonsenses and pretences of modern middle-class life.

Do not get me started.

Blimey I’d never thought of Pooter as a prototype Winston Smith, but your argument is irrefutable, G.

I never really ‘got’ Orwell’s early novels, but I think you have a point about the similarities between their main male characters and Pooter. I think my problem with Orwell is that, having taken away much of the Grossmiths’ gentle humour, he’s left with characters that are Willy Wet-legs. He needs the danger of 1984 to bring everything back to life. Pooter, on the other hand, has these redeeming qualities that make you want to like him,. Even though, it has to be said, he’s pretty beastly to his servants – a trait which, although unlikeable, makes him more complex and interesting as a character, I’d argue.

Z, I shall leave well alone.

Brit, just to underline what I said in the post: this link somehow makes one feel much more acutely the horror of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Philip: As well as being pretty entertaining, I think Orwell’s early novels are interesting as they prefigure some of the developments in his political thinking. I think he could only arrive at 1984 having explored through these novels the ins and outs of his own industrial civilisation – also inhabited by Mr P, of course.

It’s been ages since i’ve read it, but I recall laughing heartily all the way through. Great review gaw, it’s really made me want to start reading it again! I think Alan partridge has a big pooter parallel, including his Mystification at the antics of his son, Fernando.

Cheers, Worm. I didn’t know A Partridge had a son called Fernando. That name for that boy is up there with Lupin.