Toby Ferris is away this week, but has provided us with an extract from the Anatomy of Norbiton, in which he speculates on the experience of Charles VIII in Naples, how he reached his Furthest South, and what he discovered there.

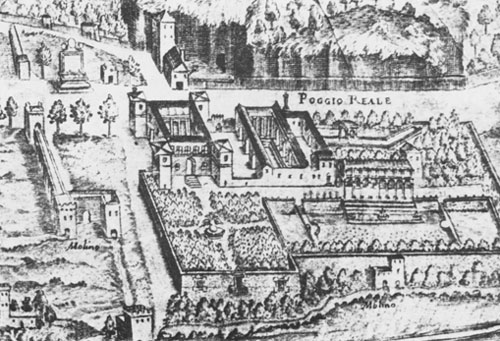

In 1494 Charles VIII of France, pursuing some tenuous antique claim to the throne of Naples, trudged his medieval army with its admittedly impressive artillery train down through the mud of Italy; and, finding his enemies divided, he casually subjugated as he went. Until, in February 1495, having barely fought a battle, he ousted the new King Alfonso from his kingdom and took possession of Naples, and of the great Renaissance villa of Poggio Reale. Poggio Reale was to be his Furthest South.

The villa had been the fruit of an extraordinary visit paid by Lorenzo de’Medici il Magnifico to Alfonso’s father Ferrante in 1480 in pursuit of peace in a different war. This was the discourse of Renaissance princes: having secured the peace after ten weeks of negotiation, Lorenzo undertook to dispatch his most celebrated architect, Giuliano da Maiano, to Naples to build a villa to match his own luminous Poggio a Caiano.

The villa flew up in a matter of years. Both Poggio Reale and Poggio a Caiano were models of grace and proportion, arcaded with slender columns and looking outward, out over their gardens and parks as a mind might reside in and order its sensorium.

Ferrante, to be sure, was a Renaissance mind not without its dark corners. Burkhardt relates how he liked to keep his enemies close at hand, “either alive in well-guarded prisons, or dead and embalmed, dressed in the costume which they wore in their lifetime”. But then Lorenzo was not without his taste for Eastern opulence; one of the features of his villa at Poggio a Caiano of which he was most proud was its menagerie with its parrots and apes and giraffes, a gift in large part of the Sultan of Babylon who, whatever his ignorance of the Classical sensibilities now motivating the greatest Italian princes, was nevertheless assured enough a diplomat to recognise that every de facto prince will relish a little gratuitous exotica.

Charles VIII, to judge from his breathless correspondence, was staggered. Dwarfish, illiterate, bursting with unmanageable boyish ambitions, at his back the dark stone inward-looking castles of France, he stood and stared slack-jawed at Poggio Reale, the perfection of its hydraulics, the shrubs in perpetual flower, the clear-scented immensity of its lemon groves, the whiteness and appropriateness of its alabasters and marbles. This was a beauty he had never conceived possible, reflecting the Albertian virtues of copia et ordo, copiousness and order, fruit of a controlling intellect.

On his return to France – kicked out the way he had come by the Pope and the Venetians and the Milanese, finally shaking themselves to some purpose – he took with him, among his spoils and retinue, cuttings from the citrus groves for an orangery at Amboise and a gardener (Pasella da Mercigliano). (Alfonso, for his part, when he had been chased from his kingdom was reputed to have fled with seeds and cuttings from his garden).

Historians have looked at Charles’s progress through Italy as, among other things, a reorganisation of European affairs, a triumph of the iron cannonball, and an end of Florentine cultural hegemony (the centre of gravity of the Renaissance would now shift definitively to the Rome of the Imperial Popes); but for Charles personally, sitting in his damp castle in Amboise, cut off from his southern kingdom forever, he had established his Furthest South both literally and figuratively – what Terry Comito in The Idea of the Garden in the Renaissance calls ‘the furthest point of his adventure out into the world’; he would, for the remaining two years of his life, surrounded by the jumble of southern renaissance spoglia, live with a newly attuned sensibility – a new sense of the possible.