Death-sweats, Paddington spectacles and gallows humour this week, as Jonathon Green continues his slang tour of London with a trip to Tyburn…

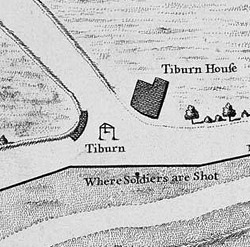

It is an old place. A crossroads where as we know wicked deeds assemble. It had a marker: Oswulf’s stone, seemingly pre-Roman and which may have been the meeting-place of the old hundred of Ossulstone which covered the whole of what’s now cis-pontine London, though the City, as ever, remained aloof. That was covered in 1819, uncovered in 1822, leant up against still new Marble Arch and lost for good when someone nicked it in 1869. There is another marker now: a plaque that recalls the crossroads’ later function.

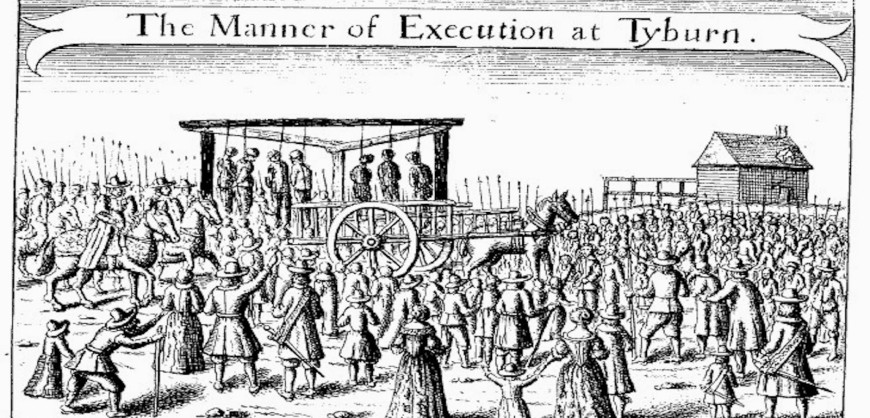

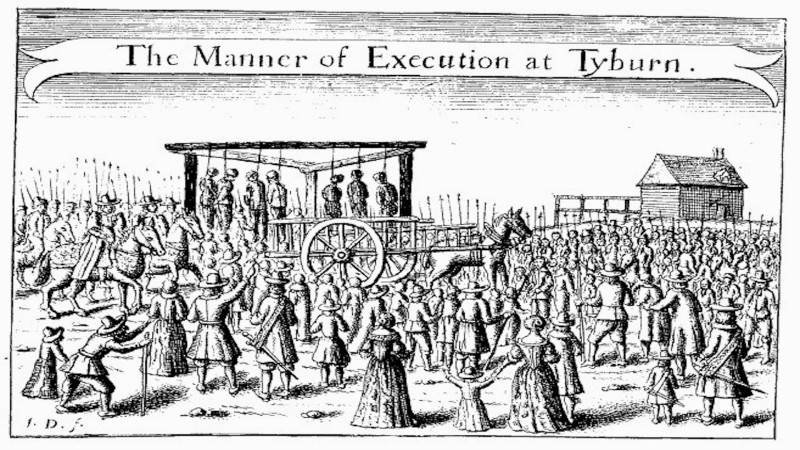

Once there was a village stream, the Tyburn ‘the boundary stream’, and where there’s a stream there’s trees and useful branches and in 1196 they caught William FitzOsbern who demanded lower taxes on the poor, dragged him naked behind a horse and strung him up. Neat. Let’s do it again. And ran out of trees, or condemned too many malefactors. Let’s get it right this time. In 1571 there’s a proper gallows, the original Tyburn tree, made of wood, with dangling ‘fruit’, aimed not at growth but at extinction. Three nine-foot bars arranged in a triangle, standing eighteen feet up on three legs. High enough for a cart and a passenger, and anyway it didn’t stop long. First to go was the ‘Romish Canonical Doctor’ John Story. You could turn off 21 at a time, and often did. The village became Paddington and they danced the Paddington frisk in Paddington spectacles, the hood.

The tree is there in miniature on John Rocque’s 1746 Map of London, though the caption reads ‘Where Soldiers are Shot’. That too. Still out on the edge, though step a little east or south and Mayfair is built and Hyde Park laid out, though western Oxford Street is Tiburn Road and Park Lane Tiburn Lane.

It would have been a well-honed ritual by then. They woke you early in Newgate (if you’d managed sleep), dressed you (some sported finery but many not: why put money into the hangman’s pocket? he made enough without flogging off your suit: selling the rope in sections, all his other perks), placed a halter round your neck and loaded you into the cart. Your coffin was already there: it served as a seat. Plus the chaplain or Ordinary of Newgate: more perks, along with the walking stationers who lined the route selling the ‘confession’ you’d never made, he had already written up your life and crimes for his own publication. It was a good gig, the industrious Ordinary pulled down maybe £200 a year.

You went West. Javelin men and constables walked alongside: the crowds were unpredictable. A long journey: three miles. Could take hours if you were a popular villain, with a few ballads to your name and pretty enough to please the ladies. Claude Du Val. Jack Sheppard. Earl Ferrers who demanded a silken rope to replace lowly hemp. Twelve hundred travelers in two hundred years. Along Holborn, stopping off at St Sepulchre’s for a drink, another at St Giles, last one at the Masons’ Arms in Seymour Place. You drank and joked with the crowd. Tears were unpopular: they threw things. You died like a dog in a string, everyone did, but not one liked a man who died dunghill. No begging, no whingeing. Try to die jannock, a bravado. And then the gallows.

You went West. Javelin men and constables walked alongside: the crowds were unpredictable. A long journey: three miles. Could take hours if you were a popular villain, with a few ballads to your name and pretty enough to please the ladies. Claude Du Val. Jack Sheppard. Earl Ferrers who demanded a silken rope to replace lowly hemp. Twelve hundred travelers in two hundred years. Along Holborn, stopping off at St Sepulchre’s for a drink, another at St Giles, last one at the Masons’ Arms in Seymour Place. You drank and joked with the crowd. Tears were unpopular: they threw things. You died like a dog in a string, everyone did, but not one liked a man who died dunghill. No begging, no whingeing. Try to die jannock, a bravado. And then the gallows.

The oldest name was euphemistic: the trining cheat, ‘the threefold thing’. Lots of imagery. Wood, trees, threes. Riding. The mare with three legs, the wooden-legged mare, the wooden horse, the horse foaled by an acorn. The triple tree, the tree that bears fruit all year round, the leafless tree; the three-legged stool, the three-cornered tree, the crooked tree, the triple trestle, the sovereign tree. The turning-tree which turned you off and let your body twist. Your writhing body kicked the clouds and you blessed the world with your heels. The sheriff had jurisdiction over executions so you danced at the sheriff’s ball and lolled out your tongue at the company.

The dying was hard. No drop. No broken neck. Just a whip for the horses and the cart moves off. It was slow, choking, and the lucky ones had friends willing to pull on their legs. You took a vegetable breakfast (‘a hearty choke’) with caper sauce, cried cockles and made a wry mouth. You pissed when you could not whistle. When the breath went so did control and the urine darkened your breeches. The anatomists struggled to tear your body away from your family who wanted to save you from the scalpel. The crowd wanted souvenirs, wiping your flesh for ‘death sweats’ which were touted as cure-alls. The hempen caudle and the anodyne necklace were more assured. A caudle was a broth given to women in labour, the necklace a quack remedy: like the rope for which they were nicknames, they killed the pain.

You had to laugh. Slang doesn’t allow for sentiment. The whole event was a Tyburn stretch (punning on time and your neck). There was a Tyburn hornpipe and a Tyburn jig either of which you danced upon nothing; you wore a Tyburn string, a tippet or a tiffany (normally a gauzy head-cover) or a piccadill which brought in another street, named for a man who made his fortune from fancy collars, from the Spanish picadillo, meaning pricked or slashed. The Tyburn collar was not the rope but a fringe of beard worn under the chin; a Tyburn collop or Tyburn face a miserable one; a Tyburn foretop a wig with its foretop combed forward over the eyes; a rakish look and villains liked them. Standing on the gallows you preached at Tyburn cross. A Tyburn bird was a criminal, surely destined to be hanged, and his young apprentice a Tyburn blossom ‘who in time,’ intoned Captain Grose, ‘will ripen unto fruit born by the deadly nevergreen’.

In 1783 it all stops. Last to go was John Austin: robbery with violence. Then back to Newgate, where the crowds were just as keen – Dickens, Thackeray among others – until in 1868 it finally went behind closed doors. Some claimed that privacy offered greater humanity. But that was never the point. ‘The puritan hated bear baiting,’ noted Macaulay, ‘not because it gave pain to the bear, but because it gave pleasure to the spectators.’

A version of this post originally appeared on The Dabbler in August 2011.