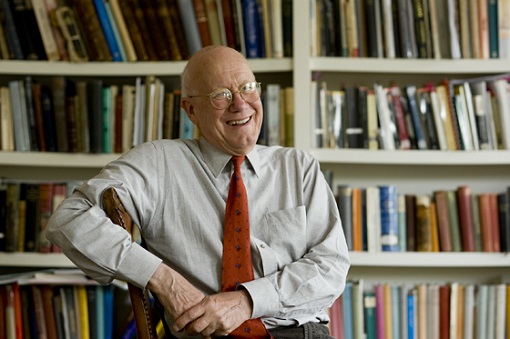

Nige salutes the extraordinary lit-crit of Christopher Ricks…

Despite the heat having knocked out most of the thinking parts of my brain, I’ve been reading (technically re-reading, as I read it when it came out some 40 – 40! – years ago) Christopher Ricks’s Keats and Embarrassment. It presents the poet’s acute sensitivity to embarrassment as an index of his extraordinary moral intelligence and imagination. And golly it’s good. Surely no one reads a text as closely and sensitively as Ricks. Here he is in full flow, exploring a single line from The Eve of St Agnes:

…Who but Keats would have ventured upon the hazards of sea-weed? ‘Half-hidden, like a mermaid in sea-weed’. Yet the sea-weed to me epitomises the central strength and sanity of Keats’s erotic poetry: its creation of a double sense, both within and without the eroticism, so that we both are and are not one of the lovers themselves. The point about a word like sea-weed, and about the thing itself, is that it arouses strong mixed feelings; it is both fascinating in its tactile pungent oddity and yet faintly repellent. It would need a Gaston Bachelard to do justice to the psycho-analysis of sea-weed [!], which is a really suggestive and strange thing to contemplate; children can unmisgivingly delight in sea-weed, but adults would be reluctant to admit the compound of sensations it can elicit. Why this matters is that in Keats’s line it is ‘sea-weed’ which precipitates the double sense, fascinatingly attractive to the lover (and so to us in so far as we are he) and at the same time odd, faintly repellent and faintly ludicrous. It is the incorporation, within the large apprehension, of this faintly embarrassing possibility of response that makes Keats’s poetry at once truthful and generous. Truthful, because we cannot, even in imagination, become the lovers whom we see and sympathise with; generous, because it becomes neither aloof nor embittered by its recognition of the possibility of embarrassment or distaste in a full imagination of the physicality of others’ love. It is not hard to be undisconcerted, unenvious, unprurient in the face of others’ physicality in love, if your sympathetic imagination simply lets no full sense of physicality in; and on the other hand it is not hard to have a full sense of such physicality while letting its embarrassment dominate your response and turn it to distaste or monkishness. But what is hard, and what gives the sense of warm spaciousness to Keats’s imagination, is to let the inevitable sense of a possibility of the distasteful or the ludicrous be accommodated within a full magnanimity. It is not only the damaged men in Zola who feel pain when they contemplate the loving happiness of lovers embracing; the freedom from envy and prurience is not simply and easily available provided that we refuse to be ‘anti-life’ or warped, and the saying ‘It is so, let it be so, with a generous heart’ is a hard saying. Until quite recently, the young were discouraged from holding hands in public because it gave the middle-aged such pains in the stomach; this was not good, but nor would it be good to make out that only those who are in a bad way would ever feel any such thing. Keats’s poetry is animated by a very real sense of the threats to calm and to benignity which can spring from any active imagining of and noticing of other people’s intimacies and pleasures; his respect for fantasy is a concomitant of his being so simply realistic in his hopes and expectations about human goodness.

Phew. This is Lit Crit on a pretty exalted level – do they still write it like this? I rather doubt it. Ricks’s amplitude and openness of mind and heart is quite extraordinary, and in combination with his attentive sensitivity to nuance and pin-sharp judgment (he’s quite clear about when Keats is writing poorly and falsely), this study makes for bracing reading. Ricks has no fear of getting too close to his subject; indeed it’s clear that he loves Keats, both as man and writer (who could read the letters and not love him?). He is not afraid, either, to stay silent when there’s nothing more to say. He quotes in full Keats’s heart-breaking last letter, and writes:

How staunch and imaginative it is of Keats that, at the moment when he is indeed taking leave, he can so perfectly accommodate his undisguisedly tragic suffering to a rich and simple solicitude for the embarrassment of others. ‘I always made an awkward bow. God bless you!’ It must be the least awkward bow ever made, and this for the saddest, fearful final blow. There is no more to say of it than that it brings tears to the eyes.

Indeed – ‘staunch and imaginative’. The best thing of all about Ricks’s book is that it sends you back to the poems, and to those incomparable letters, with new eyes and a widened appreciation of Keats’s greatness, his ‘unchariest Muse’ and his ‘widest heart’.

Until quite recently, the young were discouraged from holding hands in public because it gave the middle-aged such pains in the stomach

Really? In the stomach, you say?

Keats and Embarrassment came out just before I went to University and I aways wondered what Keats was embarrassed about and what on earth Ricks was on about. Regrettably essay deadlines on Montaigne and Dante prevented my ever reading the book. Now it seems that Keats was embarrassed to be thinking about others having sex. Am I right? Is that what the mermaids/seaweed business is about? Was Keats a bit virginal and squeamish about it all? I love Keats but it reminded me of Byron’s comment reference to Keats as “the masturbatory poet” (could be apocryphal). What’s all this embarrassment business about? Can you help?

Read the book, Guy! It’s certainly not all about sex…

Will do my best Nige but am currently reappraising Conrad, (and pleasurably so). Ricks says “the possibility of embarrassment or distaste in a full imagination of the physicality of others’ love.” and “what gives the sense of warm spaciousness to Keats’s imagination, is to let the inevitable sense of a possibility of the distasteful or the ludicrous be accommodated within a full magnanimity” In this passage its sex (mermaids and seaweed etc) and CR suggests that Keats found these things distasteful. Why, I wonder? Half the activity on the modern internet demonstrates that most adult humans don’t feel this way at all. CR makes Keat’s coyness or embarrassment a virtue. Seems strange to me.