David Long’s new book A History of London in 100 Places tells the capital’s incredible history through 100 buildings, details and places, from Roman barges to Boris Bike stations. In the first of three exclusive extracts for The Dabbler, David looks at William the Conqueror’s White Tower…

This is still by far the most tangible and durable symbol of the Conqueror’s hold on England and over the English. Very much the dominant feature of the Tower of London (and indeed in its day of London as a whole) the White Tower is not Britain’s largest Norman keep – that honour belongs to Colchester Castle – but it is by far the most magnificent.

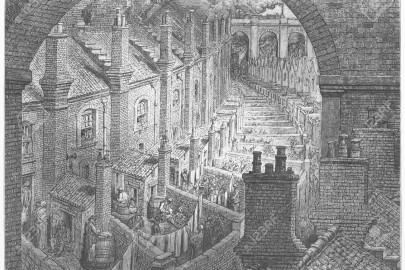

To reinforce the impression given of the new Norman supremacy, the stone was imported from Caen in France and the tall walls regularly whitewashed – hence the name. Even without this refinement, however, its immense bulk, rising ninety feet into the air, means it would have towered over the hovels and workshops of William’s subjects to a far greater extent than even the largest Roman building.

Its construction was also very much a reaction to local hostility rather than an attempt to forestall it, a series of riots having followed William’s coronation in Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066, a deeply symbolic event from which the Saxon population had been expressly banned. The Normans perceived a need for what a contemporary chronicler describes as ‘certain fortifications … against the fickleness of the vast and fierce population’ and a suitable spot was quickly found on which work for such a structure could begin.

What is still technically a royal palace more than nine hundred years later was at first a relatively simple structure of wooden walls and defensive ditches, and evidence of the latter has been found suggesting that the original complex covered only slightly more than a single acre. But by 1077 Gandalf, Bishop of Rochester ‘by command of King William the Great’ was already at work ‘supervising the work of the great tower of London’, and it is his work that the visitor can see today.

In fact it is likely that the tower was still far from finished a decade later, when William died following a riding accident in 1087. But looking back this is neither here nor there, for even without the completed building the sheer scale of the work in hand would have been enough to awe most Londoners – exactly as intended.

With the benefit of hindsight the White Tower is also the most tangible reminder of William’s sense of destiny. From the start his avowed intention had been for the Normans to remain in England, and that is how history was to play itself out. It was not until 1216 that this country finally had a king (Henry III) who had actually been born on native soil, not until Edward III (1327–77) that we had a king who spoke English, and of course even now much of the richness and variety of the English language still depends on that early injection of Norman French.

Today much of the interest for visitors to the White Tower depends on this intertwining of the two countries as much as it does on the building’s antiquity. It is, for example, very much ‘our’ Tower of London in a way that, say, Hadrian’s Wall is still viewed as something alien, an atmospheric but uncomfortable reminder of Britain’s subjugation by a foreign enemy. The tower is also interesting because of its expressly multi-purpose role as a royal home, a prison, a garrison and armoury, and even for a while a menagerie or zoo.

Almost from the start it was intended to meet these many different needs, in particular the ceremonial and residential ones as well as the purely military. But, even knowing this, it comes as a surprise to step from outside and into St John’s Chapel, from the military domain into the sacred, and into what remains the most original and most authentically Norman parts of the entire building.

The White Tower, after all, has stayed reasonably close to its builder’s original intentions, but the appearance of the exterior is actually quite different as a number of typically narrow Norman windows were made larger in the eighteenth century. No such changes were ever made to the chapel, however, which – simple, austere and harmonious – is as a consequence as near-perfect an example of early Norman church architecture as one could hope to find anywhere.

With its rounded arches, simple, stocky stone columns, and sturdy, robust groin vaults, it is a very pure expression of the early Normans’ architectural ideal. This makes it seem a more natural and somehow more organic composition than later buildings incorporating the soaring and technically ingenious pointed arches that came to define the Gothic in later centuries; also one with a hewn-from-the-solid feel, which perhaps better than any other conveys the energy and force with which the Normans recast England in their own image.

It may once have been painted in bright colours, but now with little in the way of decoration or adornment, and a style that seems to celebrate the virtue of simplicity, it is to be counted among the most bewitching of London interiors from literally any era.

Has anyone living in London ever actually been to the Tower? It seems to be one of those places like Madame Tussaud’s that no one local has ever visited

It’s a great day out, worm – there’s literally a day’s worth of things to do there. As is often the case with days out, young children and school holidays combine to send you there. Huge, lumbering, flesh-eating ravens were perhaps the biggest hit.