Journalist and author Peter Watts, proprietor of The Great Wen blog, gives us a run down of some of the latest book releases exploring our capital city

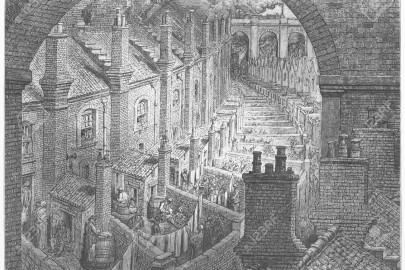

I don’t think anybody, with the possible exception of Will Self, really knows what psychogeography means but that doesn’t mean there’s not a lot of it about. For years, the London writing landscape has been dominated by three masters of the genre, the Ackroyd-Sinclair-Self trinity (in this interview, Self distinguishes between their different approaches) – it’s hard to find a book in the Museum Of London bookshop that doesn’t have an intro penned by one of them – but that is starting to change. In the past year or so, three books have been written by debutant writers that take a broadly psychogeographical approach – you can tell this by the use of words like ‘palimpsest’ and liminal’ – to the city or patches thereof but are happy to present it in a more approachable, less LRB-approved style.

The man above is Nick Papadimitriou, and his Scarp is the most Sinclairian of the three, written by a man obsessed with a small parcel of land on the city’s northern border. ‘I’m trying to get below the surface into something that’s moving in my mind as much as in the landscape,’ he says, which doesn’t say a great deal and is therefore as neat a summary of his obscure methodology as you are likely to find. Scarp is a wonderful book, a brilliantly obsessive and beautifully observed celebration of the meditative quality of what Papadimitriou calls deep topography and the rest of us know as walking. It’s also classic psychogeography in that you read it in the knowledge that a significant proportion of the theorising is total codswallop, but at least it is entertaining codswallop, an intriguing combination of the occult and broad generalisations about place drawn from a tiny physical space.

Next up in This Other London by John Rogers, a lighter but similarly intentioned account of ten walks – ‘a plunge into the unknown’ – around fairly random parts of London that were previously just strange names on old maps to the author, a film-maker and good egg. Rogers has none of the astonishing familiarity with his territory as Papadimitriou and he makes a virtue of this, imbuing the book with the joy of new discovery. It is, as a friend noted, a salute to the rewards of simple rambling, of going somewhere unusual and just strolling, or flaneuring to use the specific vernacular of psychogeography. As an alternative guide to London walks – or an inspiration to do the same yourself – it is a marvel.

Finally, came Gareth Rees‘s Marshland, hallucinatory, speculative non-fiction about the marshes of Hackney and Walthamstow that combines Scarp‘s deep knowledge about a specific locality with the dry wit and accessibility of This Other Land. Again, Rees is fond of that psychogeographical turn of phrase – ‘There is no final draft of London’, being a particularly fine example – but laces it with humour as he explores this odd landscape of rave holes, filter beds, football pitches and reservoirs (and a fascinating landscape it is too), mixing in a bit of fiction and even offering an audio soundtrack. Rees has a tremendous, natural, written voice and the book fairly skips along. I loved it.

Finally, came Gareth Rees‘s Marshland, hallucinatory, speculative non-fiction about the marshes of Hackney and Walthamstow that combines Scarp‘s deep knowledge about a specific locality with the dry wit and accessibility of This Other Land. Again, Rees is fond of that psychogeographical turn of phrase – ‘There is no final draft of London’, being a particularly fine example – but laces it with humour as he explores this odd landscape of rave holes, filter beds, football pitches and reservoirs (and a fascinating landscape it is too), mixing in a bit of fiction and even offering an audio soundtrack. Rees has a tremendous, natural, written voice and the book fairly skips along. I loved it.

All three books are a lot of fun and that is the great, dirty, secret of psychogeographical writing – it is hilariously fun to do as you train your brain to make grandiose statements about people, place and history that you are fairly sure won’t stand up to any great inquisition but look fucking brilliant on paper. Bill Drummond’s neat summary of psychogeography is perfect – ‘An intellectual justification for what I have been doing most of my life’.

I do not consider myself to be a psychogeographical writer (and here I express some of my dislike of it), but that’s not to say I’ve never indulged in it myself of occasion (as here, when writing about Wappingness), particularly when asked to do so by property developers, who seem to love this style of writing as a way to signify their deeper engagement with the city they are hoping to exploit.

By my experience then, psychogeography is used as much to shift property as it is to expand and combine the frontiers of space and mind, which is perhaps inevitable in London, where any amount of folklore and fauna only really has any value if it can be seen to have a positive effect on land prices. I’m not entirely sure that this is what Guy Debord was hoping for when he first conceived his theory of situationism, but given that he’s long gone there’s not a great deal he can do about it.