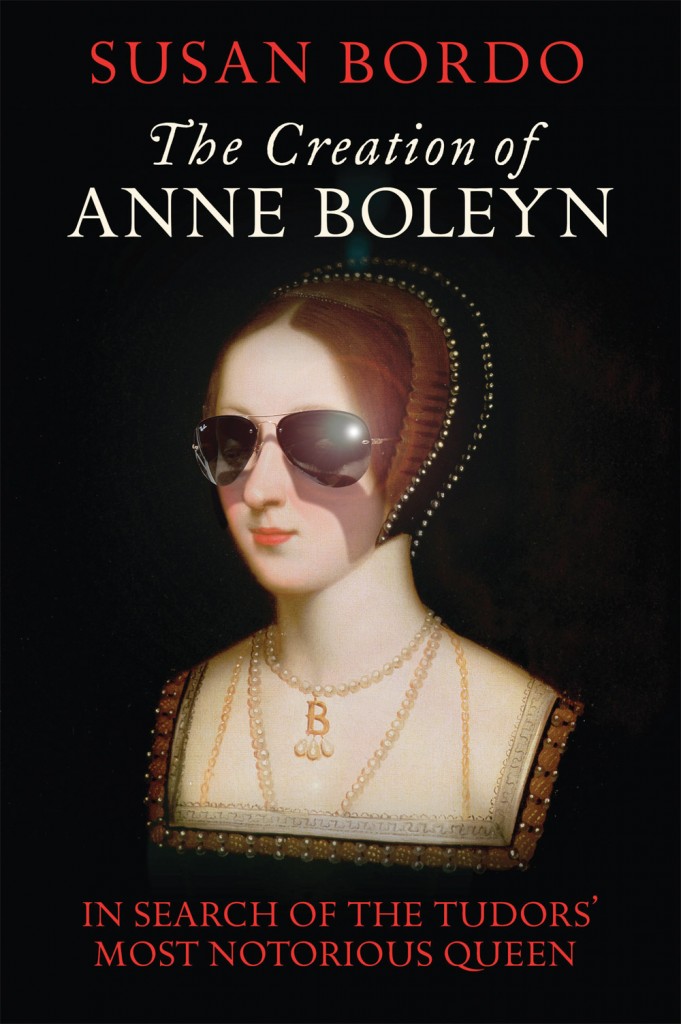

Today on The Dabbler we feature an interview with Susan Bordo, author of last month’s Dabbler Book Club choice, The Creation of Anne Boleyn, the popular new historical biography that seeks the true story behind the Tudor’s most notorious queen…

Hi, Susan; I’d like to begin by asking what your original impetus was for writing The Creation of Anne Boleyn?

The book developed organically from what was initially simply a fascination with the story of Anne and Henry and the tumultuous, history-altering nature of their relationship. But the more I read (and viewed), the more I felt I had a “job” to do as a cultural historian and critic. I was struck, to begin with, by how many depictions—historical as well as fictional—portray Anne as a stereotypical temptress. The cartoonish quality of Anne the femme fatale just didn’t seem believable to me, so I decided to dig further into the primary sources, and became quite addicted to what I came to think of as my cultural detective work. I found that, indeed, much of what we think we know about Anne just doesn’t hold up under scrutiny. But I also found that Anne the manipulative schemer, although she remains our “default Anne” (as I call her,) is far from the only historical image we have of her. I became fascinated by how different political/religious agendas, fashions of various eras, major changes in gender roles and other factors have affected how Anne has been portrayed. Thus, the “creation” (and re-creation) of Anne Boleyn.

Very early on in your book you note that there are hardly any contemporary descriptions or paintings of Anne to rely on. When you began to write the book did this lack of contemporary sources worry you?

The lack of contemporary sources is actually a large part of what motivated me to write the book, because despite the paucity of reliable information, so much of dubitable nature has been passed on as though it were historical fact. The book is not a biography, it’s an exploration of how and why so much of the “history” of Anne’s rise and fall has been constructed out of rumour, gossip, mythology, and sometimes downright lies. Of course, when I came across information that I trusted and felt revealed something important, I did speculate about “what really happened” and “what she was really like.” But I was always careful to qualify my theories as speculative, because there’s so little, really, that we can know with any certitude.

Do you think Anne Boleyn is so popular precisely because we can’t prove anything about her, allowing anybody to project their own mores and ideals upon her?

Yes, I do. Anne is an enduring mystery—and always will be, given the lack of surviving sources “in her own words” or reliably reported by non-biased contemporaries. What did Henry see in her? What made her so compelling—and so divisive—a personality? And then, having pursued her relentlessly, had a child with her, split England in half for her, how could Henry so callously order her death? These are questions that can only be approached speculatively, but the temptation to come up with answers is perennial, in part because the events that surround Anne’s life and death are so dramatic and historically momentous, and in part because the lack of firm evidence allows each historian, novelist, screenwriter, actress, and reader to imagine that they can lay hold of the “real” Anne. I know I began with that fantasy—and quickly had to give it up!

Historian Eric Ives called Anne Boleyn “the most influential and important queen consort England has ever had.” Do you agree with him?

I can only answer that with caution, because having devoted myself to her for eight years Anne inevitably looms very large for me! Having said that, I would agree with Ives. However you look at Anne’s influence—whether or not you believe that she introduced Henry to major reformist ideas, for example, or simply see her as the object of a passionate desire that “inadvertently” exacerbated the growing split between Henry and Rome—her impact on the trajectory of Henry’s reign was enormous. And since Henry himself was a history-altering monarch of very large proportions (no pun intended,) so Anne’s importance in English history is proportionately large.

Anne’s influence on Henry, I believe, was not just during her lifetime but also after her execution. I think that the long years of pursuit, the struggle against the Church, the bloodshed, and then finally the imagined betrayals that culminated in her execution changed Henry. He was always a dangerously fickle man, who could turn hot and cold on a dime; but executing Anne, I believe, was a kind of “tipping point” which put the “cold” side in permanent dominance.

In the process of writing did you find yourself overturning a lot of your own prejudices about Anne and Henry?

I’m not sure I’d describe it as overturning prejudices, but I certainly learned a huge amount while writing the book. I was truly surprised to discover the shaky foundations of much of what has been written about Anne, even in some works by respected historians; I guess I was a bit naïve, expecting more rigor from a discipline that distinguishes itself as factual rather than fictional. I was also amazed, as I mentioned in my first answer, to discover how many different “Annes” there have been over the centuries. As far as my own prejudices go, I’m an extremely sceptical reader (my philosophy training, no doubt) and my tendency has always been to take received wisdom with a large dose of suspicion. This doesn’t mean I don’t have biases—everyone does. But while I’m a feminist, I wouldn’t say that I came to my study thinking, for example, that Anne was a blameless victim and Henry a ruthless predator. That kind of “villains” and “victims” thinking has never appealed to me. Rather, my brand of feminism inclines me to sniff out and analyse gender (and other) stereotypes rather than perpetuate them. So, for example, as soon as I saw the opening credits of The Tudors I wanted to write about the clichéd ideas that were visually depicted—Katherine with rosary, Anne with heaving bosom, Henry’s eyes glowing dangerously, etc. But it’s not just pop culture that presents us with such clichés; even in as celebrated a work as Wolf Hall, Anne appears as little more than a cartoon vixen. Since Anne is a bit player in the novel, it doesn’t take away from the brilliance of the work, but it does cry out for a bit of cultural analysis. I got myself in hot water with Mantel-lovers for calling that one out—but I wouldn’t have been doing my job if I hadn’t.

Many thanks to Susan for her insights into her fantastic new book, our January choice for The Dabbler Book Club. You can order your own copy of The Creation of Anne Boleyn here. And why not sign up to our Dabbler Book Club if you haven’t already – more details can be found on our book club page.