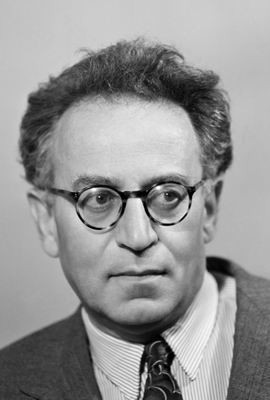

A true master is enjoying a revival of interest – today we take a particular look at Vasily Grossman’s An Armenian Sketchbook.

In 1998 I stumbled upon a Russian novel called Life and Fate. I was surprised because I had never heard of it or its author Vasily Grossman, yet by its size, Tolstoy-echoing title and subject matter (the book was about Stalingrad) it was obviously supposed to be important.

I bought it and was soon drawn into Grossman’s world; I remember standing on crowded trams, unable to put down this imposing brick of a book. Life and Fate was excellent, a profound meditation on war, Stalin, and much else – and yet it was also totally obscure. This was bizarre. Was I wrong? Was it actually rubbish?

Fifteen years later and Grossman’s star is on the rise. Life and Fate has been serialized on BBC radio, and the British edition of his war journalism was edited by Anthony Beevor, the man responsible for the bestselling history book Stalingrad. Recent editions of his work even come with a glowing blurb from the nigh pensionable literary enfant terrible Martin Amis.

Grossman’s posthumous success has also encouraged publishers to take a chance on his “lesser” books. The most recent example is An Armenian Sketchbook, a work of non-fiction about Armenia, a country I’ve long been fascinated by but have never visited. Barely longer than 100 pages, it is Grossman’s account of two months he spent in the country in the early 1960s while translating an Armenian novel.

Now, the two most common pitfalls that await the travel writer are:

1/ Since travel is pretty easy these days, and anybody with the cash can arrange a trip to just about anywhere, the journey will be uneventful and unremarkable. This leads authors to fill pages with boring paraphrases of stuff found in history books.

2/ Since travel is pretty easy these days, and anybody with the cash can arrange a trip to just about anywhere, the author will contrive a cringe-worthy gimmick to add “spice,” like driving around Eastern Europe in a Trabant or traveling the Silk Road on a bicycle.

Grossman’s book comes close to category one. By his own admission he did nothing, went nowhere and met nobody. Most of his time was spent working. He admits he doesn’t speak Armenian (his “translation” was in fact a literary rewrite of a literal translation) and he doesn’t even pepper the reader with historical factoids. By all rights the book should be very, very boring.

And yet it isn’t.

Partly this is because An Armenian Sketchbook functions as a literary time machine that takes us to a vanished civilization: The USSR of the 1960s. Especially interesting is the section on the Stalin monument that at the time was still standing in Yerevan, Armenia’s capital. Grossman records the sudden change in people’s attitudes from “hysterical worship” to complete denial that the dictator had any role to play in the creation of the Soviet state: Both represent the same total lack of objectivity, he argues.

Best of all however is when Grossman writes about the “nothing” he did. I refer in particular to two remarkable episodes in which Grossman – the author of a profoundly moving epic novel about Stalingrad – describes his agony, anxiety and ultimate ecstasy as he is caught short in public nowhere near a WC.

Yes, friends – that’s how little happened during his trip to Armenia.

Now, in the hands of most authors, a detailed analysis of toilet trouble would seem otiose if not crass. But Grossman is different: A true artist, he is able to reach deep into the essence of his bladder torment on a Yerevan bus. The legendary war correspondent, who witnessed so many terrible things, discovers empathy, indeed a commonality with all living creatures via this most mundane of experiences.

Grossman’s second and more serious toilet emergency occurs towards the end of the book as he is en route to a village wedding. This sequence is even more striking, because it leads to an encounter with an Armenian villager who starts talking about Grossman’s writings, and the terrible suffering of the Jews under Hitler. Grossman was not only Jewish, but he was one of the first journalists to write about the mass executions of Jews during World War II; and yet most of his writings on the topic had been suppressed within the USSR. But now, in this village, during a celebration, he experiences a sudden and completely unexpected moment of kinship with a member of another ancient nation which had also been subjected to terrible suffering throughout its existence, including a 20th century genocide. The scene seems to come out of nowhere, and Grossman does not labor it when it does arrive; and yet is deeply moving.

I don’t think I’ve ever encountered an author who could shift from (literal) toilet humor to an account of radically different people united by horror so effortlessly and without striking a wrong note.

Life is full of contradictions, but while Grossman makes it look deceptively simple, that kind of radical tonal juxtaposition is very difficult to pull off in literature. A true master of course can write well about small moments as well as epic battles, and so while Life and Fate is exceptional, so too is An Armenian Sketchbook: Thus Grossman was doubly great.

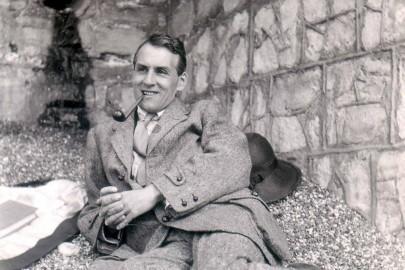

He was a wonderful writer – I have Antony Beevor to thank for discovering him. Thank you for the review, I will look out for this one.