What does the flight of an arrow describe for us today?

In my last post, speaking of horses, I concluded that we were losing a certain collective mental shape, and I now find the same to be true of the flight of an arrow.

I was a spectator at the Olympic women’s team archery a week or so ago, and, an archery novitiate, was surprised to discover that I could clearly see the arrow in the air, arcing away towards the target. It was a strangely logical sight – a Renaissance philosopher might have concluded that the bow must necessarily release energy in the form of a bow – but it was also a thing of beauty: rapid, precise, and, with the barely audible sequence of pluck, flutter and thud, softly musical. And, for piquancy, a little bit deadly.

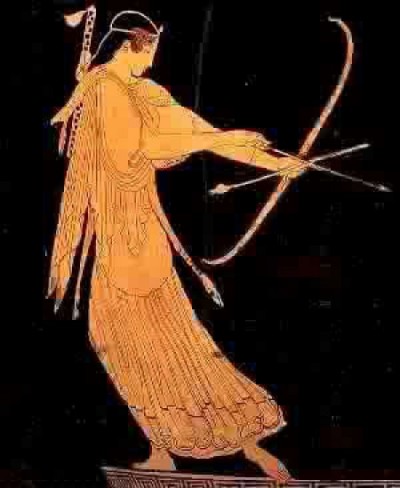

It was a beauty, moreover, that was once commonplace. The bow was the weapon of Apollo and of Artemis. You might need to spear a boar or a lion, but the gods loosed arrows at bucks and hinds, animals which were emblems in their own right of mechanical motion realised as liquid flow.

Around this thin line of beauty there is a familiar if vanishing cultural and metaphorical accretion. The arrow is a ubiquitous image of directness and swiftness, of unerring aim and lethal flight; of power operating at a distance. It lodges in Harold’s eye (perhaps), or hangs in Assyrian stone, a mark of kingly power and unfailing retribution.

Archers are lithe, graceful, elegant; or they are brutal, impassive. The archers in various martyrdoms – of Saint Sebastian, for instance, or Ursula – are conduits of tyrannical power. The barbarity of the twinned Pollaiuolo bowmen and crossbowmen in the National Gallery (below) is in part generated by their use of crossbows, which are cranked machines compared with the traditional bow; and in part by the fact of their taking point blank aim. The compression of the trajectory is an aesthetic affront, translating the visible unfolding of intention and judgement inherent to a shot with a bow into an invisible and instantaneous assault.

The key to the beauty of an arrow flight, to repeat, is the fleeting but visible arc. In this it is unlike its modern analogue, the bullet, which makes its passage like a jittery electron, jumping from point to point. We struggle to comprehend that a bullet dropped from shoulder height and a bullet simultaneously fired parallel to the ground will land at the same time, just as we struggle to understand superposition, the multiplicity of quantum states. The flight of a bullet has, in a sense, passed beyond a perceptual threshold. We need to figure it to ourselves in other terms.

Not that bullets do not have their trajectory. My father, who was a gunner-navigator in the fleet air arm towards the end of World War II, said that, given the contrary motion of planes, the vagaries of wind and fear, and the difficulty of calculating for bullet drop over ranges that were hard to distinguish against cloud, a gunner would do well to splatter his target with four or five rounds in a thousand, a strike rate which would leave a Mongol horseman smirking with incredulity, but which testifies, like wandering tracer rounds, to a wilful and impetuous arc.

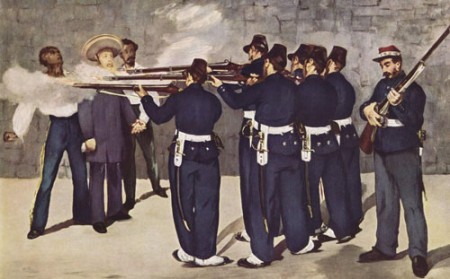

This arc is susceptible to the same drama of violent compression as in the Pollaiuolo canvas. In Manet’s Execution of Maximilian, the victims of the firing squad stand at the end of an arc so short it tends to a flat line, even to a point in space, an instantaneous all-comprehending explosion.

The rifle, of course, has its epiphanies of marksmanship and cool-headedness, just as the bow does; Yul Brynner or James Coburn allow their shooting to unfold across space and a fragment of time. Thus just as there is a gulf of grace between Artemis hunting deer and the archers shooting Saint Sebastian, so is there a gulf between Manet’s firing squad and Steve McQueen protecting Mexican villagers from tyranny.

The archers that I saw in action last weekend, were of a different, less carefree breed. Their discipline demand a metronomic, and you might say bureaucratic repetitiveness; one of the Chinese archers has a pressure mark running down her face, across her lips and chin from the countless thousands of precise draws she has made. They are sporting bureaucrats: diligent, methodical, unflappable, mildly sinister, like secretarial assassins. But I am sure that they take pleasure in the arrow flight and its easy perfection, in an ideal form realised unerringly, again and again.

I wonder if in ‘ye olden days’ there were many archers with pressure marks down their faces from over use of the bow? And if so, whether this was ever captured in a painting?

Surely our modern-day darts players are the ‘carefree breed’ you seek?

Not sure actually Gaw. They always seem a sweaty and uptight bunch (if you’re talking of the professionals) – not really of the Alan-a-Dale, Lone Ranger cast of mind

Olivier, as director, certainly knew how to portray the beauty of the arc and, in the case of Agincourt, the deadliness that lay at its conclusion:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GyZYiKpkHDE