Mr Slang traces the original Dabbler – a ‘babu’ conceived by Rudyard Kipling…

The lexicographer’s role being not to anticipate but to analyse I was not here for the creation, and am therefore unaware whether or not the quote that provides both rationale and motto for the Dabbler’s daily efflorescence was sourced. If it was, then I stand corrected since what follows is thus otiose, but if not, I shall expound. The full quote, from Kipling’s Kim (1901), runs as follows:

The old lady, more or less veiled behind a window, returned to the vital business of green-mango colics in the young. The lama’s knowledge of medicine was, of course, sympathetic only. He believed that the dung of a black horse, mixed with sulphur, and carried in a snake- skin, was a sound remedy for cholera; but the symbolism interested him far more than the science. Hurree Babu deferred to these views with enchanting politeness, so that the lama called him a courteous physician. Hurree Babu replied that he was no more than an inexpert dabbler in the mysteries; but at least – he thanked the Gods therefore – he knew when he sat in the presence of a master. He himself had been taught by the Sahibs, who do not consider expense, in the lordly halls of Calcutta; but, as he was ever first to acknowledge, there lay a wisdom behind earthly wisdom – the high and lonely lore of meditation.

Hurree Chunder Mookerjee, MA (Calcutta) is a babu, defined as ‘an Indian man (especially a Bengali) who has had a (superficial) English education and is somewhat anglicized; an Indian clerk or minor official who is able to write English; (in later use more generally) an Indian office worker or bureaucrat.’ And, adds the OED, ‘Frequently depreciative and in later use often offensive.’ As a representative of that thorn in the side of colonial hierarchs – what those whom Kipling besought to assume the white man’s burden would term an ‘uppity nigger’ – the babu presents his far from politically correct creator with a problem. To Kipling’s credit he solves it by resisting too much deprecation and allotting him the role of player in the Great Game of espionage – pitting the Lion against the Bear, who may not have secured Constantinople, as the song correctly predicted, but is still slavering over Hindustan – and as such a member of the fictional spymaster Col. Creighton’s ‘Ethnological Survey’ (in reality the Survey of India) under the codename ‘R.17.’ As we meet him in Kim, the babu is usually disguised, works in the toughest of conditions, and combines his researches as a cartographer with spying for the Raj.

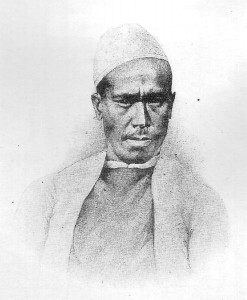

Such figures existed in flesh-and-blood. Kipling may have encountered them and was certainly aware of their labours. The pundits, as they were known, were first memorialized by the Times-man Perceval Landon in his book The Opening of Tibet (1905). ‘I do not know that there are many feats in the world of adventure, endurance, and pluck that will compare favourably with that of the Indian native intrusted with the work of secret exploration in Tibet.’ Europeans were rigorously excluded from the country but no outsider was welcome. Landon noted their egregious intelligence, their physical toughness, their unswerving loyalty and was sure that ‘the work of these lonely spies, twirling incessantly within their wheels rolls of blank paper instead of prayers, which are laboriously and minutely filled up night after night with the day’s observation, must receive a place of honour second to none.’ Among the most celebrated was ‘Krishna’ (Kishen Singh 1851-1921 – pictured below), cousin of the well-known trader-explorer brothers Nain Singh (top) and Mani Singh Rawat, and it was he, Landon was certain, upon whom Kipling modelled his babu, although that honour has also been claimed for another pundit, Sarat Chandra Das. For those who would like a proper look, it is worth starting here, though I have no doubt there is much more to be read and appreciated.

In the way that Dickens created the sympathetic (and as such overly sentimental) portrait of the Jew Riah in Our Mutual Friend as, it has been claimed, atonement for the anti-semitic clichés embodied in Fagin, so does Kipling seem to have used Kim’s Hurree Chunder Mookerjee at least in part to make up for a much crueller portrait in Departmental Ditties (1886), where he mocks another uppity babu, one ‘Hurree Chunder Mookerjee, pride of Bow Bazaar, / Owner of a native press, “Barrishter-at-Lar”.’ who rose so far above himself as to attempt a little arms dealing. This babu is no hero, and Kipling sees him off, having the authorities depute a gang of ruffians to murder him in return for appropriating his consignment of weapons: ‘What became of Mookerjee? Smoothly, who can say? / Yar Mahommed only grins in a nasty way, / Jowar Singh is reticent, Chimbu Singh is mute. / But the belts of all of them simply bulge with loot.’ That, as they doubtless said at the Club, would larn him.

The real-life ‘Krishna’ was pensioned off in 1885: he was still fit and up for work but his identity was known, the Tibetans had put a price on his head and he could no longer maintain cover. He had surveyed a total of 4750 miles, walking some of the world’s least accessible areas. Kipling’s Mookerjee returns to the shadows as Kim ends, but fiction has resuscitated him in the Tibetan-born Jamyang Norbu’s pastiche The Mandala of Sherlock Holmes (2001). Set like many such ‘missing’ tales in the period that follows Holmes’ disappearance after killing Moriarty at the Reichenbach Falls, it is based on the great detective’s explanation to Watson, following his return to London in the canonical story, ‘The Empty House’: ‘I travelled for two years in Tibet . . . and amused myself by visiting Lhassa and spending some days with the head Lama. You may have read of the remarkable explorations of a Norwegian named Sigerson.’ Moriarty also reappears, risen from the abyss and now attempting to poison the Dalai Lama. The babu, set to watch Sigerson by Col. Creighton, who believes him to be ‘playing’ for Russia, discovers his real identity and promptly takes on that of an Asian Watson. Purists will disapprove but the book, with its concatenation of two great fictional figures, is nothing if not fun. One must hope that neither Kipling nor Conan Doyle would have objected.

Wonderful stuff as usual… But incidentally… ‘chunder’… is the vomit meaning of Indian origin?

No, mate. It’s from Oz. I quote GDoS:

According to Barry Humphries (b.1934), the great popularizer of the word in his ‘Barry Mackenzie’ strip in Private Eye and on film, f. naut. shout of warning ‘watch under!’; thus Humphries, Collected Barry Mackenzie (1988) ‘Jeez I’m sorry lady — I forget to yell watch under’. He also offers rhy. sl. f. Chunder Loo of Akim Foo = SE spew, to vomit. Chunder Loo featured in a long-running series of advertisements for Cobra boot polish (c.1910–29), drawn by Norman Lindsay (1879–1969) (and occas. by his brother Lionel) published in the Sydney Bulletin. Thence it moved from public school sl. to surf jargon to popular use; Brian Moore, Lexicon of Cadet Language (1993), adds ? link to UK dial. chounter/chunter/chunder, to grumble

Babus do not come off well in Kipling’s fiction in general. Of course, in Kipling foreigners are permitted to be primitive and brave (Gurkhas, Sikhs, Pathans, Americans, some of the Irish) or cunning and deceitful (others of the Irish, pre-1914 French and Russians), but seldom to combine brawn, brain and virtue, so the babus are in broad if not flattering company.

In memory of the unfortunate arms dealer, let me leave a link: http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poems/r-k