A major new academic work on Wittgenstein reveals the human face of a brilliant but difficult man, finds Elberry…

In an age of meretricious academic nonsense, Wittgenstein in Cambridge is a professional, scholarly work. Professor McGuinness has collected and edited nearly 500 pages of letters between the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein and various Cambridge luminaries, including Bertrand Russell and JM Keynes. In one sense it is an arbitrary selection – as if the target audience are Cambridge alumni associations. Yet it is a good enough limitation.

Wittgenstein, like many philosophers, distrusted academia. He was, however, involved with Cambridge University for over twenty years, first as a student and then as a teacher. The rest of the time he was in a deliberate wilderness, in the First World War (as a volunteer), then as a schoolteacher in rural Austria (he requested to work in the poorest villages); and after resigning his position at Cambridge he did his best work in Ireland, as a private citizen.

Wittgenstein in Cambridge sketches some of the tensions, and attractions, of academia. Most of all, in Cambridge he found people to talk to. As a young man he wore Bertrand Russell down with the prolonged intensity of his thought, and his tempests of Germanic fury; nonetheless, the affection, the need for friendship, is evident in these early letters. And equally evident is Wittgenstein’s inability to endure compromise. He formally broke with Russell in 1914; in Russell’s words:

I have had a letter from Wittgenstein saying he and I are so dissimilar that it is useless to attempt friendship, and he will never write to me or see me again. I dare say his mood will change after a while. I find I don’t care on his account, but only for the sake of Logic. And yet I believe I do really care too much to look at it. It is my fault – I have been too sharp with him.

Russell in many ways came to represent academic vice to Wittgenstein – a great mind turned to populist journalism and self-satisfaction. In 1911, however, Russell was still a great man, and he had opened a door in Wittgenstein’s life. Breaking with him was not so easy; from Wittgenstein’s letter to him (February 1914):

I shall be grateful to you and devoted to you WITH ALL MY HEART for the whole of my life, but I shall not write to you again and you will not see me again either. Now that I am once again reconciled with you I want to part from you in peace so that we shan’t sometime get annoyed with one another again and then perhaps part as enemies. I wish you everything of the best and I beg you not to forget me and to think of me often with friendly feelings. Goodbye!

One thinks of Wittgenstein as an engine with almost no tolerance – the slightest imprecision, mismatch, would threaten to tear everything apart. Thus later letters strike a similar note with Keynes and the great economist Piero Sraffa. This was inevitably exhausting for everyone. After visiting Wittgenstein in Austria in 1924, the mathematician Frank Ramsey writes to Keynes:

I’m afraid I think you would find it difficult and exhausting. Though I like him very much I doubt if I could enjoy him for more than a day or two, unless I had my great interest in his work, which provides the mainstay of our conversation.

From the evidence of his biographies, Wittgenstein didn’t really have friends – only disciples and intellectual antagonists. He evidently required a good deal of handling. After writing one of his characteristic letter to Keynes (“And what followed this […] showed me what amount of negative feelings you had accumulated in you against me”), the economist replies, equably:

What a maniac you are! […] No – it was not “an undertone of grudge” that made me speak rather crossly when last we met; it was just fatigue or impatience with the difficulty, almost impossibility, when one has a conversation about something affecting you personally, of being successful in conveying true impressions into your mind and keeping false ones out.

Over time, Wittgenstein seems to have understood the effect he had on others; and while he didn’t modify his behaviour (which would have meant changing his self), he was too intelligent not to notice the pattern. So, in 1946 he writes to the amiable philosopher GE Moore, after Mrs Moore asked to postpone their usual meeting a week:

I should like to know whether what Mrs Moore wrote to me was an honest to God invitation for me to come and see you on Tuesday, or whether it was a kind of hint that I’d better not try to see you. If it was the latter, please don’t hesitate to say so. I will not be hurt in the slightest, for I know that queer things happen in this world. It’s one of the few things I’ve really learnt in my life. So please, if that’s how it is, just write on a p.c. something like “Don’t come”. I enclose a card in case you haven’t got one. I’ll understand everything. Good luck and good wishes!

Of course he would have been very hurt, since he liked Moore. There is something rather painful about Wittgenstein, who would habitually crush and exhaust his interlocutors, supplying Moore with a postcard with which to reject him, and pretending to be calm and English about it. One has a strong feeling for his uncertainty in English society, as an Austrian first of all (my German students are likewise often either too direct, or far too indirect and polite, because they’ve heard the English find the Germans rude), and secondly as one raised in a kind of test tube, apart even from ordinary Austrians.

That the dons suffered Wittgenstein was in part for the sake of his remarkable mind, and perhaps partly because his rages and manias seemed the shadow cast by his own self-dissatisfaction. As he writes in 1913, to Russell:

Sometimes things inside me are in such a ferment that I think I’m going mad: then the next day I am totally apathetic again. But deep inside me there’s a perpetual seething, like the bottom of a geyser, and I keep on hoping that things will come to an eruption once and for all, so that I can turn into a different person. I can’t write you anything about logic today. Perhaps you regard this thinking about myself as a waste of time – but how can I be a logician before I’m a human being! Far the most important thing is to come to terms with myself!

Philosophy, for Wittgenstein, was work on oneself. Beginning with hardcore logic (even Russell didn’t really understand the Tractatus, Wittgenstein’s first work), and ending in “speech therapy”, emphasising the ordinary foundations of all language, Wittgenstein’s philosophy tended from mathematics and abstraction, towards the particular and the human. In this regard, in 1938, he writes to Maurice O’Connor Drury (a student who became a psychiatrist):

The thing now is to live in the world in which you are, not to think or dream about the world you would like to be in. Look at people’s sufferings, physical and mental, you have them close at hand, and this ought to be a good remedy for your troubles. […] Look at your patients more closely as human beings in trouble and enjoy more the opportunity you have to say ‘good night’ to so many people. This alone is a gift from heaven which many people would envy you. And this sort of thing ought to heal your frayed soul, I believe. It won’t rest it; but when you are heathily tired you can just take a rest. I think in some sense you don’t look at people’s faces closely enough.

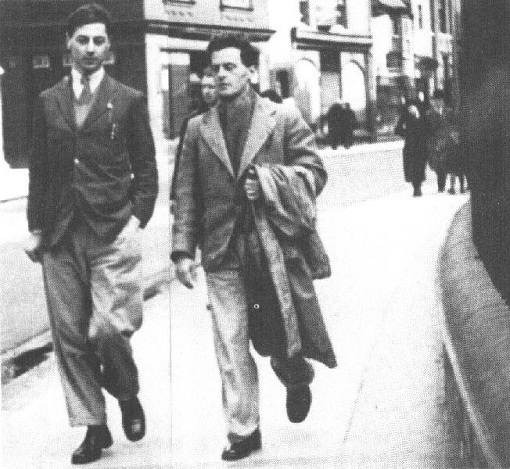

One could say, this book takes a close look at Wittgenstein’s face; and whether or not this will interest anyone, he was nonetheless a human being and so it may have value.

Regarding wittgenstein’s postcard, that seems very Germanic, as they are great lovers of the passive-aggressive note: anyone who has lived there in an apartment will have come across various messages left on the doormat involving reproachment for some minor transgression like walking too loudly