How various Towers of Babel can remind us – rather surprisingly – that we shouldn’t wish for everything to be translated into the simple and straightforward.

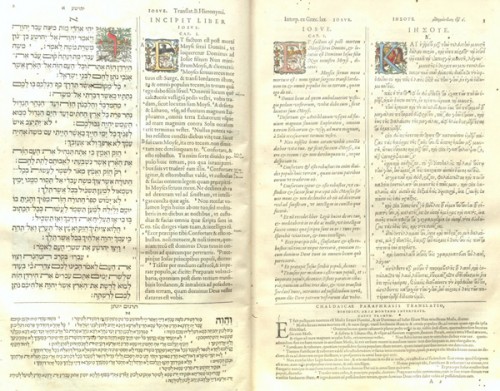

It is not hard, these days, to access a polyglot Bible if you find you need one – they’re ten a penny on the Google – but they are no longer objects of wonder. The great age of the Polyglots was the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when a number of enormous projects were brought to fruition: the first, the so-called Complutensian Polyglot was published between 1514 and 1517 in Spain; the last, and arguably the most accomplished in terms of its scholarship, was that edited by Brian Walton in England in 1654-57. But perhaps the greatest of them, in terms of textual accuracy, printed quality, and cultural weight was the Antwerp Polyglot of 1568-72, printed by Christophe Plantin and known as the Bibia Regia.

The Plantin Polyglot was prepared over five years, in eight volumes, the last two of which contain appendices, dictionaries, and maps. It is in five languages: Greek, Latin, Syriac, Hebrew and Aramaic (and there are also some passages in Chaldean); the Greek and Hebrew Old Testaments each have a Latin translation, with an Aramaic version below and a Hebrew translation of the Aramaic. The New Testament is in Greek and Syriac, each with its Latin translation.

It was both a remarkable work of scholarship and a technical achievement. The Plantin press was a pioneer of oriental fonts, printing not only in the languages of the Bible but, from the 1590s, in Arabic too; and there was an enabling humanist culture in Antwerp in the middle years of the century – for instance among his intimates and associates Plantin numbered Pieter Bruegel; the geographer and cartographer, Abraham Ortelius; and the neo-Stoical philologist and philosopher Justus Lipsius.

However, these were dangerous times to be overly-clever. For all that it acquiesced in the provision of bibles in a variety of baffling languages, the Catholic Church was congenitally suspicious of Biblical antiquarianism, and the Antwerp Polyglot stood at the dangerous leading edge of scholarship.. Thus in spite of the fact that the Bibia Regia was prepared with the express permission of King Philip II of Spain and under the personal supervision of Arias Montanus, noted theologian and the King’s private chaplain, the finished work was nevertheless denounced to (albeit subsequently cleared by) the Inquisition on the grounds that it had, of necessity, consulted original manuscripts and other sources, and must therefore be tainted by either (or both) Calvinism or Rabbinical Judaism.

The Church was perhaps right to be suspicious, even if it could not pinpoint the reasons for its unease. These menhirs of scholarship, whether by design or accident, were built to shiver the simplicities of faith, and bore witness to an ongoing diffraction of Truth. Just as the scientific advances of the seventeenth century, predicated as they were on the invention of the telescope and the microscope, ensured that the Truth of the cosmos was no longer available to mere contemplation, so the Truth of revelation as laid out in the Bible now eluded the unaided grasp of Faith. It had to be actively grappled in, fragment by fragment, detail by detail, and pieced together with philological precision.

At around the same time that the Antwerp Polyglot was conceived and executed, Pieter Bruegel was painting his Towers of Babel, the earlier of which (signed and dated 1563) now hangs in Vienna, and the later (before 1568) in Rotterdam.

Neither painting depicts the Biblical version of events, exactly. The Vienna Tower includes a colossal King (usually identified as Nimrod) tyrannising his masons, and a tower that appears to be chiselled out of a mountain, bits of which project though it at various points.

The Rotterdam Tower, perhaps the more interesting of the two, is a contrastive work; for all the subtle variety of its architecture in detail, it is a harmonious construction with a well-graded winding ascent; it is not hubristic, but an orderly, neat and habitable tower caught in the encouraging roseate glow of the dawn, the natural emanation of a productive people working undirected, cooperatively.

Given the ordeals of the Netherlands in the 1560s – the multiplying religious discord, the gathering rebellion against the Spanish overlords, the bouts of violent iconoclasm – neither Bruegel’s Rotterdam Tower nor the Polyglot support the fiction of a Universal Language; both, rather, testify that the proper foundation for tolerance, liberty and prosperity is not a series of simple virtues simply stated – simplicity was a recipe for inevitable discord and repression – but a subtle, tortuous, complex, fractured and unending process of negotiation. As Sir Francis Bacon, denizen of the Age of Polyglots, would later observe, ‘all rising to a great place is by a winding stair’.

The Atlas of Norbiton is a weekly bulletin from Norbiton: Ideal City of the Failed Life. Unlike its more comprehensive, detailed and discursive mother site, the Anatomy of Norbiton – the Atlas is intended as a pocket guide to the Failed Life for Failed or Failing Individuals on the move.

There’s this bit of interesting info about Babel from Wikipedia –

The phrase “The Tower of Babel” does not actually appear in the Bible; it is always, “the city and its tower” or just “the city” . According to the biblical etymology, the city received the name “Babel”, from the Hebrew word “balal”, meaning to jumble.

Interesting – thanks Worm. If I could only read a polyglot Bible, I’d probably have known that.