So how would Norbiton mark the passing of the Olympic flame?

The Olympic flame is approaching, relayed from Cornwall like news of a shiny corporate rainbow armada; and the sight of it makes me impatient to reclaim the idea of procession for Norbiton.

There are varieties of procession, of course – there are those that veer towards triumph, those that are coded displays of power and hierarchy. A procession is partly intended to destroy the individuality of its components, to dissolve them in some greater rolling spectacle; and partly designed to set off some one aspect of it, since such processions are not merely linear but lumpy, the ordering of their segments not sequential but hieroglyphic. You can, as it were, read the power relations in the presidential motorcade.

But at its root the idea of a procession is a sane and useful one. Processions are an old fashioned form of public assembly and work best at modest scales – they are good at expressing the aspirations or fears of desires of at most a few thousands or tens of thousands of people: more or less a cityful. And so down the centuries people have processed statues of the Virgin, holy relics on saint’s days, condemned prisoners in tumbrils, the Maestà of Duccio, newly-elected Lord Mayors, FA cups, and so on.

Times change of course, and in spite of some reliquary evidence to the contrary, we are no longer a culture that comfortably processes. The Olympic torch relay, for instance, falls somewhere between goofy pilgrimage, trade jamboree, and the sort of made-up healthy ritual so beloved of the Nazis. This is not a ceremony that is going to bind us in awe, you feel.

How then to reclaim the procession? Well, I am working on a theory of anti-processions, wherein a crowd does not line a street, or march towards something, but disperses from something. A football match, for example. Or a crucifixion.

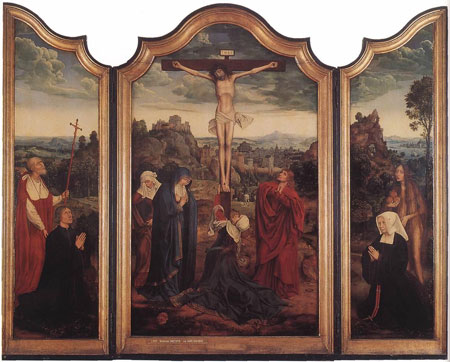

In Antwerp in the Museum Meyer van den Bergh there is a large triptych by Quentin Matsys which shows a crucifixion with donors, and in the background a view of Jerusalem and its hinterland.

The drama and peculiarity of the scene ostensibly lie in the dolorous foreground; but we have seen too many crucifixions, too many odd saints and donors, to be long distracted by it. More interesting is the evolved cityscape and landscape behind, the port, the turrets; and most interesting of all is the straggle of dispersing spectators, a tenuous tendril of humanity slinking back to town, some on horseback, some on foot.

To stand in front of the Matsys is to stand in a quiet room in a generally quiet museum; to turn away from it is to drift around the museum or back into town, or back to the business of your life. The dispersal, if you can call it that, on both sides of the picture plane, is a dispersal of ones and twos. Unlike the spectators at the crucifixion, you have not been witness to a cosmic event or ghoulish sideshow; there is no carnivalesque discharge of tension. But as with the aftermath of, say, an unimportant football game that happens to have been lost, there is the same grumbling transference of a shared experience, the same distribution of it like a mosaic of common trouble through the city.

This same granular, contrarian spirit can on occasion be ignited in the assembly rather than the dispersal of the crowd, as a sort of loose and unformalised procession. Bruegel paints just such a grouchy carnivalesque gathering in his Christ Carrying the Cross of 1564, where the crowd, a degenerate aggregation of liberated children, squabbling itinerants, low-level criminality and bolting horses, simultaneously swamps the drama and animates it.

There is no hierarchy of suffering here, and no authorised or organised gaiety. It is this sort of ragtag half-cock procession which, crucifixion aside, the citizens of Norbiton might conceivably enjoy, were they actually to settle down (in the manner of the solitary pedlar, bottom centre, with his mad outsized backpack and wooden spoon) to watch the Olympic procession pass nearby.

I was interested to hear that during the Chelsea victory procession through west london on Sunday, people threw celery at the players – why, I haven’t the faintest idea.

any decent procession needs a palanquin I reckon

there’s a song Chelsea fans sing which goes ‘Celery, celery..’ to the tune of She wore a yellow ribbon (‘Cavalry! Cavalry!)’, the lyrics of which would have made John Wayne blush. Suffice it to say they have little to do with the merry month of May. Celery gets thrown around in matches, or used to. No one I’ve spoken to has any idea why.

I’m off to watch the torch pass by at precisely 5.01pm. I’ll wave.

Catholics, trades unionists and royalty seem to be the ones who go on processions in England. I think everyone else finds them embarrassingly expressive.

Yes, we had to process around the boundaries of my parish when I was small, on some Marian errand or other. In Seville I was witness to an extraordinary spectacle, a huge statue of the Madonna on a wooden platform the size of a boxing ring, underneath which were visible only the shuffling ankles of about fifty men. They could manage to move it about two or three metres at a time. There was a trumpeter and a drummer, and everyone was out in the evening and having a good time.

And that reminds me of the story of Mahler in New York, witnessing the funeral procession of a firefighter; Alma, his wife, related that the procession stopped under the windows of their hotel and in the silence there was a single great thwack on a bass drum and the procession moved on; when she looked across to the next window there was Mahler, not all that far from death himself, tears streaming down his face. The thwack founds its way into the beginning of the finale of the 10th Symphony

http://youtu.be/uzGVhxEYjY4?t=52m29s

I confess I’m not indifferent to a marching band.

Charles Ives’s father was the military bandleader in Danbury, Connecticut, He liked to have two bands marching from one end of town to another in opposite directions, playing different tunes. When they passed each other, the discordant racket thus resulting had a profound effect on the tiny tot who became America’s greatest composer. So, yes, marching bands are undoubtedly a good thing.

Aren’t marches different from processions?

I’d have thought a march could be integral to a procession – I remember being taken to the Lord Mayor’s show in the 1970s and that seemed to involve lot of marching.

And Charles Ives – thanks Frank. Goes some way to explaining his scrambly brain and scrambly music – his loony father perhaps more than the dualling bands

this is an interesting bit of semantics – what is the exact difference between a march, a procession and a parade? The government and police have to differentiate these things slightly when it comes to demonstrations, especially in Northern Ireland