This week, Gerhard Richter and the grottification of cities – it’s another extraordinary bulletin from Norbiton…

Norbiton is a city of Ideas, not of stone, so on my occasional visits to London, I am struck by how rapidly a stone city can change: set down a crane and over weeks and months it imperceptibly reconfigures the material base of the city in a precise arc around itself. Cities, for all their robust petrifaction, come and go, piecemeal or wholesale. There are plenty of Babylons and Jerichos and Troys buried in the dust of the deserts of the world. And of those still standing to us even the old, tired cities are in a continual state of excited flux, to say nothing of the cosmic upheavals of a Shanghai or a Beijing.

A few months ago I visited the Gerhard Richter’s retrospective at the Tate, and in among the squeegee paintings and the photorealism and the colour sequences, I found myself looking at the stadtbilder, or Townscapes. Richter painted and perhaps still paints in batches, and in the late 1960s he turned out 50 or so canvases, mostly in shades of grey, white and black, depicting aerial views of European cites – Madrid, Paris, Stuttgart, and others.

They are notable for an effect difficult to capture in reproduction: they have a way of dissolving and reconstituting themselves as you move toward and away from them, so that from a few yards back they are clearly cityscapes, but closer to they are wobbling unstable blobs and smears of paint. Somewhere between the two there is a tipping point, where the cities appear to be emerging from or returning to some proto-city form, not inappropriately for European cities hanging between carpet-bombed destruction, invigorating but lopsided post-war growth, and H-bomb annihilation.

The idea that a city can slip into and out of form, pass from one state to another, is one we find hard to comprehend despite our plentiful experience of it. Stone and its cognates – brick, cement, concrete – are unlikely materials to represent the instability of form, matter passing out of and into recognisable structure, not because they are unchanging – the names of the categories of rock (metamorphic, sedimentary, igneous) suggest otherwise – but because we rarely see it change. We kick our toes against it and it resists. As materials go, it is always just there.

For the Renaissance, however, such an instinct would have been foreign. Stone and rock were the bones of the earth – the teeth, thought Marsilio Ficino (‘How can it be said that the womb of this female is not living? This womb that spontaneously gives birth and cares for so many offspring, that sustains itself and carries teeth and hair on its back?’) and were subject to change, to mutability. Matter was unstable, malleable, Protean. The God of the Renaissance –or at any rate the god of the humanist-magus – was a plasmator god, constantly working and shaping the raw matter of the cosmos, moulding it into form.

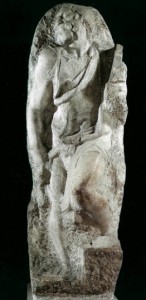

Hence the fashion for the grotto and its emblematic place in many Renaissance gardens. The grotto was an artificial subterranean place of flowing water (fountains, sometimes actual springs) and coruscations of stone, pumice, shells, and it was associated with the generative spots of the earth, just as we might think of the mid-Atlantic ridge with its oozing magma, or the subduction trenches of the pacific rim, strange hyper-processual regions where intransigent materials are slowly worked, the freshest stuff of the planet. It was in one of the most celebrated of the Renaissance grottos, that in the Boboli Gardens at the Palazzo Pitti, that from the 1580s Michelangelo’s emerging or vanishing stone slaves were, appropriately, placed.

And the Renaissance city, by a curious analogy, is also subject to grottification. There is no such thing as the Renaissance City, as Lewis Mumford pointed out, except in imagination; Renaissance buildings – palazzi, churches, cod-pagan temples – inhabited medieval cities, so many rational cuckoos crammed into the narrow streets, amid the mud and the gothic; as though these classical, or at any rate stile nuovo buildings were precursors to or remnants of forgotten cities buried beneath the muck and confusion. One way or another, these new edifices, like the bones of lost empires alongside which they were placed, were an index of change.

And our own rupestral cities, as Richter intuited, for all the homogeneity of new development, are similarly so many vast and indistinct grottos, passing into and out of form under our oblivious feet, chaotic but somehow uninhabited – as Proust noted of Society Paris, you would no more think of addressing a stranger than of addressing a mineral – alienating yes familiar, so much transformation masquerading as growth.

If we had spent our formative years in rainy Düsseldorf with those weirdo’s Sigmar Polke and Konrad Lueg, wouldn’t we overpaint townscapes, just like him.

Not to mention Blinky Palermo.

The problem for Richter is that Polke haunts him, when it was decided to devote one large room of the Bonn Kunstmuseum, in the Museum mile, to Richters work they kinda bunged in a bit of Polke’s stuff. To get to Gerhard you had to clamber over Sigmar, as Polke’s stuff looks like a painter and decorators bib and brace….considering Richter’s iron grip on his work and where it is shown, this is surprising

Richter’s ability to to produce a modern piece that blends with the ancient, his transept window in the DOM, seen on a bright day, is a thing of wonder, in reality a giant farben, it complements its surroundings.

awesome as ever – Hadn’t seen these Richter paintings before, I like them, they remind me strongly of the photographic series Oblivion by David Maisel

Interesting, thanks for the link – Richter was working from photographs (but perhaps that’s obvious) which he culled from magazines, and which he later collated in Atlas (appropriately enough) as for example here http://www.gerhard-richter.com/art/search/detail.php?11686

The Richter really is outstanding art. Meanwhile we have Hirst….

Staple or Sissing?

..or Geoff or Patty..

I found that Richter exhibition stupefying. So much to take in at one viewing.