The Atlas of Norbiton is a weekly bulletin from Norbiton: Ideal City of the Failed Life. Unlike its more comprehensive, detailed and discursive mother site, the Anatomy of Norbiton – hailed by Nige as “a thing of strange beauty and wonder, inspired by the South London nowhere known as Norbiton” – the Atlas is intended as a pocket guide to the Failed Life for Failed or Failing Individuals on the move.

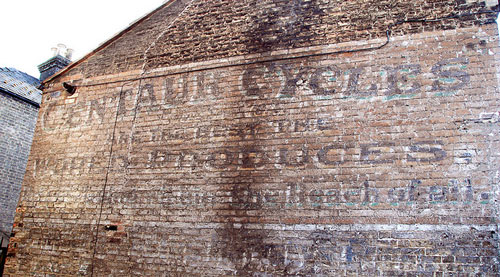

Near where I live there is a ghost sign advertising Centaur Cycles –‘the best the world produces’.

Centaur cycles were produced in Coventry roughly between 1875 and 1925. The company were known for their successful lightweight bicycles (the King of Scorchers, for instance, available from 1890, weighed only 26lb), but they also produced cars after 1900, and some monstrous hybrid single-geared motorcycles.

Centaur is of course a frighteningly apt name for a bicycle company, and I am amazed that Humber let it fall into disuse. Perhaps they found it unsettling, a reminder of a remote almost mythical past when men built flying machines and phonographs, and invented wireless telegraphy and the incandescent electric light bulb; a past when the sight of a man or woman on a bicycle flashing past must have been magical, strange, Centaurean.

The centaur, to the ancient Greeks and to a lesser extent to the Romans (by whom they had become domesticated to Bacchus) and the Renaissance, was a byword for wildness and incivility, for concupiscence and drunkenness. They dwelt in the wooded mountains of Thessaly, out on the margins of the civilised world, and ate raw flesh.

The precise nature of their anatomy took some time to settle down. Archaic representations of centaurs have a wholly human form which is propelled by equine back parts, and some with hooved but otherwise human forelegs. The monster is by definition a creature of mutable form.

![fig_2[1]](http://thedabbler.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/fig_21.jpg)

Dante places the Centaurs in his seventh circle of hell, where they roam the banks of the boiling Phlegethon, preventing the violent, who are immersed there to varying degrees, from climbing out. Virgil identifies Chiron, their leader, to Dante, calling him ‘the one who contemplates his breast’, – at once a contemplative pose and an inquisitive one, as though Chiron, the wise centaur who educated Achilles and Jason, were habitually searching out the point of contact, the shifting boundary, between his human and animal parts, his divine and bestial nature.

The blending of this point or line became in the Renaissance a byword for artistic skill. In the 5th century BC Lucian described a painting by his contemporary, the great Zeuxis, wherein a centauress is giving suck to two infant centaurs, one on her human breast and other on her animal teats. Lucian particularly praises the imperceptible transition between human and animal.

Ovid also, in his description of the battle of the Centaurs and Lapiths in Book XII of the Metamorphoses, describes the almost human beauty of Cyllarus, who is about to die in the arms of his beloved Hylomene, a scene depicted at the centre of Piero di Cosimo’s Lapiths and Centaurs.

These creatures are, in spite of the riot at their backs, tamed, subdued, almost civilised creatures. At first glance you might not even recognise them as centaurs. If the warring humours of a centaur are typically separated out in a demonstrable chromatography of the soul, then this blending, this smoothing or blurring of the line so that it almost vanishes, is a tacit admission that we are all more nearly centaurs than we perhaps wish to acknowledge.

I do not wish to suggest that Mr Polly on his King of Scorchers appeared to his contemporaries as a Conquistador to the Aztecs, a composite machine-man, ferocious, unknowable. From the forest. That would be fanciful.

But the soul of a cyclist, I like to think, is forged in a teenage breast; a cyclist is a perpetual misfit, an anarchist, a thrill-seeker, hated by pedestrians and car-drivers alike, a creature of the margins, an unsettled, semi-chained, half wild creature; a fragile precarious imp balancing at speed like a mountain goat insouciantly skirting a precipice. The bicycle, in other words, in its ghostly origins at least, is a machine of the failed life – exultant, free, absurd.

a great read! Centaurs are indeed liminal beasts

I like this bit of info, gleaned from wikipedia:

Lucretius in his first century BC philosophical poem On the Nature of Things denied the existence of centaurs based on their differing rate of growth. He states that at three years old horses are in the prime of their life while at three humans are still little more than babies, making hybrid animals impossible.

I read somewhere or other that Ovid’s stuff on the beauty of Cyrallus (and the manifold perfection of his age ‘his beard began but then to bud; his beard was like the gold’ in Golding’s translation) was a counterblast of some sort to Lucretius, or at any rate a wink in his direction. Why, I don’t really know.

Of course what Lucretius chose to ignore and what Ovid most certainly did not, was that for most adults there is a centaurish differential between the development of mind and body; so, for example, in a shop of new bicycles I still feel the urge to ride off to the wilderness and prove myself to the tribe in feats of lycra, or something. But of course the tribe would only laugh.

would the tribe laugh? Everyone I see these days in lycra puffing about on bikes seems to be over 60. (-Although I don’t live in London, where I’m sure it’s the opposite)

Fair point. I suppose the whole lycra thing – what the Guardian bike correspondent (if such a position exists) calls ‘the full gimp’ – is merely a redrawing of the line between man (or woman) and machine. Like Chiron, a lycra-wearing cyclist (in hell?) might very reasonably contemplate his or her own cyborg breast and wonder where precisely the machine stops. I suppose the true centaur-cyclist would in fact be wearing one of those all-in-one lycra affairs with braces, something at which I drew the line the last time I had a bike which might have merited it.

And to answer your question, in my case, yes, the tribe would certainly snigger.

Stupendous stuff.

I will note only one thing: that in Narnia centaurs are goodies. I think.