James Hamilton examines the phenomenon of nostalgia…

I’ve never had it: the lightly held, easily tossed-off belief that the past was “simpler” or “more innocent.” And little wonder. I spent most of my childhood obscurely but thoroughly scared; even now, many years later, I find myself disassociating under stress or seeking the means to. Nostalgia doesn’t come free: you need a certain kind of experience. I hadn’t, haven’t had it. Nonetheless, when I was a child I was obsessed with the 1920s and 1930s.

TV costume drama, daytime films on BBC2 and old family photographs gave Robert Graves’s Long Weekend a parallel existence running tantalizingly close to my own. These depictions had a confidence, a smartness and implied safety and politeness to them that gave the period a powerful prevailing imperative: it existed more strongly than we did, as though at any moment it could surge back into being and overwhelm all that had followed it.

A magnifying glass held close up to a picture of a GWR 4-6-0 Star class at Paddington could bring you so close up to the photographic dots that you could almost pull them aside like a curtain and step through. (Step through to join the young man who Hardy captures so well in Midnight on the Great Western, stunned by his intense pleasure at travelling to the beautiful city on that matchless line). But the curtain remains, and you remain, looking in.

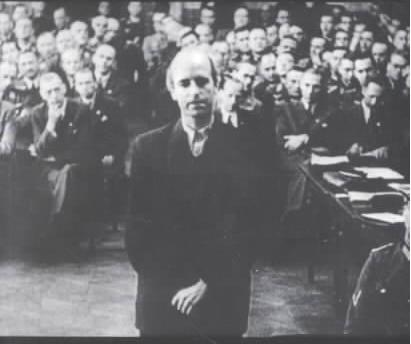

Sometimes, the photographs look out. There is one, for instance, of terrible clarity, which shows Balliol’s Adam von Trott zu Solz facing a kangaroo court after the 20 July Plot of 1944 (above). He stares back at you, entirely defeated: whatever he’s in, it’s not some lift or elevator he can just step out of. Yet it’s hard to believe that you can’t simply go in there, with a snatch squad, and get him out into the safety of 1976 or 1997.

Not all escapism is nostalgia. And not all nostalgia is false. That faint modern desire – don’t you have it? – to dart back into the shade of pre-Crash 2005 or 2006 had powerful and justified counterparts in 1919 or 1945 and the years immediately after them. Simon Garfield’s astonishing Mass Observation diary compilations of the Second War and Austerity years are packed with moments when people admit to themselves: had we known in advance it would be this bad, the knowledge might have killed us.

There are at least four such black times in living memory or what was recently living memory: the wholesale destruction of British agricultural life following the American Civil War and 1871 Smash, the Great War and 1918 influenza outbreak, the Great Depression, and World War II. Is it still nostalgia when, for vast numbers of people caught up in such events, the safety and ease of the past is straightforward fact?

Regardless of the question, it’s easy to see how the habit of seeing the past as a better place might arise in that way and install itself at the heart of a culture; how it might become a default setting in the thinking of a large chunk of the population. What happens next, though, it seems to me, is entirely political.

Because contemporary expressions of it describe a distinctly political arc. The Hovis “New World Symphony” ad and the L.S. Lowry celebration song “Matchstalk Men and Matchstalk Cats and Dogs” were 1970s creations from the moment British income equality peaked. The great Miss Marple, Poirot and Sherlock Holmes series, however, let alone Brideshead, began in the 1980s and took the point of view of a quite different part of the population.

And now? The quite different, but both wonderful, Downton Abbey and Life On Mars/Ashes to Ashes series presented us with compelling, but troubled and questioning views of the past: it’s not clear from either exactly who in society is entitled to nostalgia, or what that nostalgia, once inspired, is good for. John Simm’s Life On Mars was only tangentally about 1973 at all. It was, above all, and nakedly, about Britain looking back at the Thatcher years and asking what the hell did we do there? with guilt and sorrow implied, and then, in the final episode, having that magnificent silent debate, expressed entirely through hue and colour intensity, about what constitutes a properly felt and experienced life at all.

Which brings me back round again to fear and disassociation, because when they descend, you can’t feel: and you’re aware of the fog around you and the anaesthesia, and at the same time you’re certain that you are only inches away from a parallel existence where all that drops away and you can finally smell the air and feel the ground beneath your feet. Looking at that photograph of the GWR 4-6-0 Star class today, I feel as though there really had been life in there behind the photographic dots when I first leant over it as a child. It’s all gone now.

Great writing James! Reading this has been a lovely way to procrastinate on starting another week of mayhem at work

For some reason your images of trains and mid-century imagery brought to mind Larkin. (who was being nostalgic about steamtrains and things even as they still existed) Your last paragraph – “at the same time you’re certain that you are only inches away from a parallel existence where all that drops away and you can finally smell the air and feel the ground beneath your feet.” was terrific stuff

I suffer from nostalgia constantly. I get nostalgic about stuff that happened last week. This is in conflict with the delight I take in the debunking of golden age myths and hell-in-a-handcart theories.

A truly evocative, thought-making piece.

What’s more interesting than pure nostalgia is the way in which our attitudes to the past are so often so conflicted: most of the time, we seem to have no great difficulty in believing that the past was both a) harsh, dark, primitive, weird, stupid – the Horrible Histories view; and b) kinder, happier, simpler, full of archaic virtues and a natural grace and wisdom, common as the sun and rain. These attitudes are, I suppose, as old as humanity, every era having its myth of the lost Golden Age and its contradictory myth of progress, in which the shortcomings of the past serve to set off the glorious present. The anthropologists talk about ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ primitivism, meaning the tendency to believe in Noble or Ignoble Savages. In practice, the one has never seemed to rule out the other.

What may be new is the way in which these conflicting feelings, which once attached themselves to people and events in the deep past, increasingly set the terms in which we look at recent decades. This is one of the many things that seem to be going on in Life on Mars(it’s also what I was trying to get at in my comment on the Birmingham film). To us, the 70s and 80s have become a sort of pastoral frieze, full of gigantic half-lovable simpletons who we somehow want to look down on and up to at the same time. Is this just down to the speed of technological change, the rapid turnover of ideas and fashions? I mean, some of those people back then were probably quite intelligent, considering that they didn’t even have Google. And it’s quite sweet, the way they thought that was a good look. Pathetically lacking in hindsight, though: can you believe those great simple boobies thought Diana would be queen one day?

Personally, I’m looking forward to a great sorrowful wave of New Labour nostalgia sometime next year. Fifteen years gone over since Mr B’s Famous Victory! Were we ever so young? And how the hell did we get from there to here? Bring it all on again: Blunkett’s dog, Prescott’s jag, Mo’s wig! All gone, gone under earth’s lid. It’s all so much scarier.

I would have been happy simply to study the photograph of the GWR 4-6-0 Star class engine, later rebuilt as a Castle (without turrets, naturally), but then James added brilliant text, and I’ve ended-up wallowing in nostalgia, to the extent that after three attempts to post a relatively coherent comment, lacking in sentimental mush, about my boyhood in the fifties and the reasons for my nostalgia for an even earlier period, I’ve given up.