Historian Juliet Gardiner is one of the leading commenters on British social history. Her book The Thirties: An Intimate History – which has recently been released in paperback – was described by The Telegraph as “a quite outstanding work of social history” for “the depth of its research, the quality of the writing and the sheer richness and vibrancy of the material” in which the “cinematic clarity of Gardiner’s descriptions of accidents and ceremonies tells more about the decade than a page of statistics.”

In an exclusive post for The Dabbler, Juliet looks at some of the myths of the much-maligned decade…

The Sixties – supposedly – swung, the Twenties – allegedly – roared, yet the Thirties have Auden’s millstone ‘the low dishonest decade’ forever attached.

Demonised as an era of social deprivation, economic depression and political contumely, when rescued from this grey morass, the safety line came in the form of a suburban semi with a baby Austin in the garage. Surely there was more to the Thirties than this? Yet apart from a few books written immediately the decade was over (Robert Graves and Alan Hodge’s The Long Weekend and Malcolm Muggeridge’s The Thirties, the best) it seemed as if there was almost a moratorium on revisiting the 1930s, as if the Second World War had enveloped the preceding ten years which just seemed a sleep-walking prelude to the most terrible war the world has ever known.

Then, soon after the century turned, where there had been largely only scholarly interest, the thirties hit the trade bookshops. Roy Hattersley, Martin Pugh and then Richard Overy all published absorbing accounts of the interwar years – though each with a different take. But, convinced that the 1930s was very different to the decade that had gone before, I decided to truffle away in museums, collections, regional archives, local studies centres, reading letters, diaries, memoirs, long forgotten novels and biographies in an attempt to uncover an ‘intimate history’ of the years that were bookended by the effects of the Wall Street crash (and other economic and political factors) and the outbreak of the Second World War.

What I found went beyond the economic debate to a time of enormous interest and complexity, of grim social realities juxtaposed with a material optimism fuelled by growing prosperity and a consumer boom epitomized by the ubiquity of Woolworths, the spread of ‘Tudorbethan’ suburbs – Osbert Lancaster’s ‘bypass variegated’. But also an optimism that took a political and a cultural form, an urgent impulse to discover, to sort out and to change.

It is wrong headed to deny the problem of the 1930s – the high levels of unemployment, the failure of any effective, long term form of social welfare, the inertia, sometimes even the near callous disregard, by those in government, the cruel humiliation of the hated Means Test, the misguided misjudgments in matters of foreign policy. Yet for those living and working away from the areas of declining heavy industry, it was an era of modernity when Britain embraced new ways of living. The Thirties was a glamorous decade when speed and streamlined design in transport and decoration epitomized progress. Some Thirties buildings are among the finest architecture Britain has ever produced – though they were few and often fiercely resisted. The ‘dream palaces’ – the massive fantastical cinemas that proliferated and the audiences that filled them nightly – are eloquent witness to the desire for escapism, for a world of the imagination, while some Thirties literature is as powerful today as when it was written – the books of George Orwell and Aldous Huxley, the poetry of W.H.Auden and Louis MacNeice among them.

But perhaps above all it was the impulse to find out about the true ‘condition of England’ (and Wales and Scotland too) that was so unique – and so heart wrenching. The confidence that after the Armageddon of the First World War, there must to a better way, that science and the arts could be put at the service of politics to unlock the conundrum of poverty in the midst of plenty, that resources could be mapped, change could be planned for the benefit of all.

The Thirties was a time both of high minded planning for a better world – in housing, health, town planning, pacifism and the ‘last great cause’ fought against fascism. And this went hand in glove with the ‘democratisation of desire’, an easier life for all, more ‘things’ in fashion, make up, cars, wirelesses, household appliances. More leisure, paid holidays, regimented fun, sport for the masses, dance halls for the young- and the not so young – the opportunity to enjoy the fresh air, to roam the countryside, to cultivate the body beautiful.

Much of that optimism, many of those blueprints for change, ran into the sands and were never realized before war came in 1939 putting a definitive end to the decade before it was out. Yet many of those plans and dreams have been realized since, and still permeate our world today. In so many ways the Thirties was the crucible in which the modern age was formed. And to understand Britain today, it is worth a detour, in my view, back some 80 years, to the fingertip history that is almost beyond our reach, when many of our present day dilemmas and achievements can be found in a raw yet hopeful state of formation.

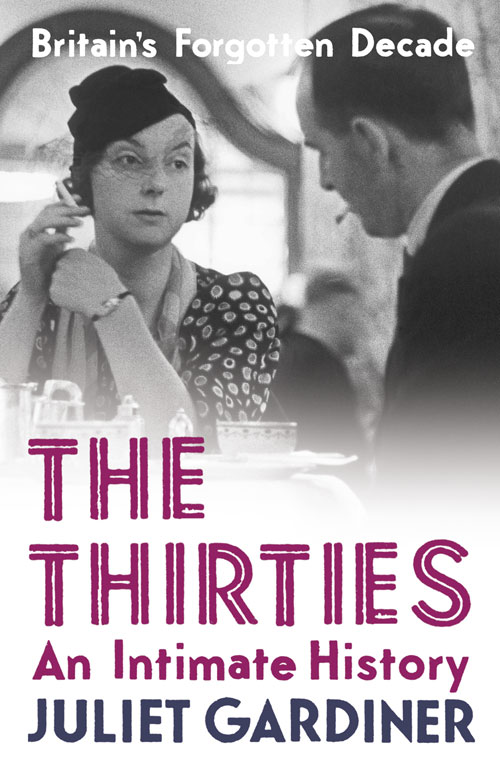

I’m in love with that photo. Any idea where it’s from or who it is?

Ian, it’s by Wolfgang Suschitsky, and *I think* it’s one of a series taken on or near to the Charing Cross Road during the ’30s. The companion pictures are well worth seeking out, but that’s the best of the bunch.

Yes James that’s right. The photograph is by Wolfgang Suschitzky . It was taken in 1934, one of a series, as you say, taken round Charing Cross Road and the couple are in Lyons Corner House – the Tottenham Court Road branch. I am pleased you like it – I find it a narrative in itself and totally compelling. I am pleased to say that Suschitzky is still alive. He came from Vienna to London in the early 1930s and took lots of photographs of London street life at that time. His sister, who married a doctor and went to live in the Rhondda Valley, took some wonderful photographs of the hard life in the Welsh valleys in the thirties – among other subjects. Her name was Edith Tudor Hart

Best wishes, Juliet (Gardiner)

Extremely cheering to hear that Suschitsky’s still with us. So is his Charing Cross Road in many ways, although he’d now have to buy his 78s from Foyles rather than.. (Disclaimer: my Scottish exile began before the recession was properly underway, and I’ve no idea how e.g. Cecil Court is faring).

It’s been something of a week for that. I found myself watching the opening titles to Raging Bull which make beauty out of all those c.1940 Speed Graphics flashing through a wall of fog and tobacco smoke as Jake La Motta jogs menacingly in his penitent’s hood.

The film leaves Jake fat and washed up in the year of the Munich Disaster, but like Suschitsky, I discover he’s still “out there somewhere, right now” too.

You’re not wrong James – and there is more wonderful stuff here –

http://www.wolfsuschitzkyphotos.com

I knew lots of the snaps – the bromide of Sean O’Casey for example – but to my shame, I had never heard of Suschitzky.

She looks impossibly glamorous, but I can’t work out whether she is giving him a hard time or perhaps suggesting that he pop round later for a game of cribbage. Either way, bring back Lyons Corner House on TC Road, imperious women with time on their hands, and fags – inside the caff.

Thank you Juliet for the leisurely look at the decade I just missed – your writing at least as evocative as the piccy

Excellent, Mahlerman. Opening up the slideshow on Wolf’s site, there’s a picture of a fat man in hat and spectacles, reading a book on the street outside Foyle’s – absolutely brilliant. Why hadn’t I heard of him either? It says he was cinematographer on Get Carter! and Ring of Bright Water.

Absolutely up my tudorbethan street, I find the thirties to be my favourite 20th c decade for all the reasons you describe

Absolutely up my tudorbethan street, I find the thirties to be my favourite 20th c decade for all the reasons you describe

Thanks for the information, James amd Juliet, and the link, Mahlerman. Yes, it’s the narrative, lots of alternative ones at that. I can’t settle my mind on the woman, who is she and what is her relationship to him? Quite plainly he works shifts in a spanner factory, a fact which makes her story all the more intriguing.

Ian, on first view I thought it was a 1936 advert for woodbines: “Oh Godfrey, show some decorum, stop blowing off your fag ash with your nose; its going in my soup”

Juliet’s book looks very interesting. It had me returning to J B Priestley’s ‘English Journey’ from 1933. In the final chapter ‘To The End’, Priestley talks about the three Englands he had seen: The Old, the Nineteenth Century, and the New, and the fascinating intermingling of the three he had seen in every part he had visited. The Old England was the country of cathedrals and minsters, and manor house and inns; the quaint highways and by-ways England. The Nineteenth Century England was the industrialised country of coal. iron, steel, mills, railways, foundries, warehouses, etc. The New England was born in America; the England of arterial and by-pass roads, filling stations, giant cinemas, cafes, bungalows, dance halls, Woolworths, and so on.

If Priestley had carried out a second journey in 1939, how would England have looked to him six years on? Perhaps Juliet’s book provides the answers.

Priestley wrote about nineteenth century Britain, didn’t he, as if it were a species of catastrophe: entire cities like Gateshead appearing in order to exploit something that would enrich a few and enslave many. And, with the crash, the only things that caused such places to make sense were gone, leaving their inhabitants high and dry in meaningless lives with nowhere to go.

He might have been writing about the early ’80s.

I’m really interested in your question about how Priestley might have written the same book but in 1939 – certainly, his Western Avenue “American” Britain was really up and running by then – sometimes you look at all those 30s semis and they still seem to be crouching somehow, trying to duck the Luftwaffe – the Mitchell Library Online has an extraordinary series of photos from this time of Glasgow shopfronts – they might be in Detroit and on shorpy.com for all the difference that’s there. The late ’30s was the first period of real, palpable decline of things like the Miners’ Institutes with their libraries, theatres, colleges and choirs, caving in to cinema and falling incomes alike. That might have got his attention.

I’m sure it would have got his attention, James. This has made me think of what a trip in ’39 by Priestley, accompanied by Betjeman, would have given us? I would have relished reading those two completely independent accounts of the same roads, the same villages, the same towns and cities, and the same people.

I never used to enjoy social history that much until I came across David Kynaston’s Tales of a New Jerusalem (two volumes published, four to go). This sounds as if it takes a similar approach so is now winging its way to me.

Hopefully Juliet’s book is rather more slender than Kynaston’s, which, over the course of two enormously weighty tomes, have left me rather apprehensive as to whether I’ll survive finishing the next four….

Slender? There’s always the Kindle! but it’s worth having this fall on your nose a couple of times, believe me.