Jonathon Green – visit his website here – is the English language’s leading lexicographer of slang. His Green’s Dictionary of Slang is quite simply the most comprehensive and authorative work on slang ever published. Today, with Lent soon to begin, Jonathon launches an epic survey of the Seven Deadly Sins of Slang…

The Cut-throat Butchers, wanting throats to cut,

At Lent’s approach their bloody Shambles shut;

For forty days their tyranny doth cease,

And man and beasts take truce and liue in peace.

John Taylor ‘Iacke-a-Lente’ 1620

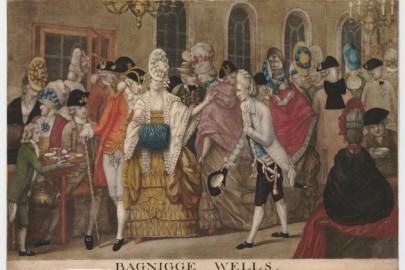

Lent shortens Lenten – its original form, since turned adjectival – and Lenten comes from Germanic roots all meaning lengthen and refers to days as more hours lighten towards spring. Only in English is there a religious aspect: the self-denial of the forty days that follow the one-time apprentices’ bacchanalia of Shrove Tuesday. The Seven Deadly Sins were created for home consumption around 1340 but they boast classical antecedents and while they have no theological link to Lent they each reflect an evil of the un-denied self. Slang, the sinful tongue, explicates them all and so, as Lent moves on, shall I. There are seven virtues too (compassion, chastity, that kind of thing) but rest assured, slang has no place for such.

You say gourmand and I say gourmet but we both say glutton and that equates with greedpot, but greed in general terms is another sin and will appear in due course. What we have here is what Bertie Wooster would term browsing and sluicing, and material covetousness, the world of gimme, must await its turn. This week’s sin is gluttony and today’s star guest is Monty Python’s Mr Creosote.

Gluttony and its fleshly incarnation the glutton (which is where slang, never liking to get too abstract, prefers to focus) go back to Latin glutire which means to swallow or choke down and makes its way forward via French gloutonerie and Scots gluther. Its first cited appearance in the OED is as a sin, and St Luke recounts the parable of the rich glutton who ‘fared sumptuously every day’, denied the unfortunate Lazarus the scraps from his table, and with the smug moralism of licensed superstition, ends up turning on Satan’s spit.

Slang doesn’t do morality – if it wishes to ponder consumption it turns to Rabelais – but it does do derision. Glutton as such takes us back to pugilism, where his gluttony is for ‘punishment’ and as the European magazine punned in 1809: ‘The term glutton whether at a fight or a feast is now indiscriminately applied to every man of true bottom.’ (The dumb glutton, en passant, was a female attribute, being the vagina, and to feed it was to have sex.)

It’s mainly about the guts, the belly. First in line is the 16th century’s greedy-guts, followed by gobble-gut, garbage-guts, guzzle-guts, gully-guts (gully being the throat down which food pours as does water along a gully or gutter), the guts-ache, and the gutser (which latter can also be a breath-depriving throw from a horse). One can be gutsy and gutty, which in the culinary context will only be seen by some as courageous. There is gorby-guts (sometimes cut to gorb) which seems to come from Scots gorb, an unfledged bird, its beak ever-open for mama’s next wriggling deposit. Ireland extends gorb as gorbelly, the glutton. The gorge, a standard term for throat, serves slang here as well.

Next in line the bellygut, which is the bellygod in the Caribbean where pronounced belagot it can also mean an outsize cooking-pot, the animal or human intestines (‘tripes’), and in metaphor something inward and intimate, e.g. private family matters (and thus the belly-word, something one keeps to oneself). The Caribbean is keen on gluttons, offering the big-belly, the longmouth, the sweetmouth (synonymous sweet-lips is English), and the nyamy-nyamy which comes from nyam, to eat. To gaze gluttonously is to big-eye or strong-eye, and to be struck or craven which comes not from craven meaning fearful, but from craving, desirous. The target of such entrancement is perhaps the belly-bottom concrete, a large, round boiled dumpling. Licky-licky, with its image of taking tentative licks rather than bites, is primarily defined as pernickety and choosy as to one’s food but by extension it means never satisfied, and thus gluttonous. A more recent use in the UK black community refers to drinking to excess.

Back with the belly one finds the belly-paunch (which eventually gets a bellyful), and belly-furniture, which is food. The 18th century adds the long-stomach. Dogs are always up for food, thus a pair of hounds: the chow hound uses the Anglo-Chinese pidgin chow, a mixture (of any kind) and thus food; the hashhound takes in hash, a mess or jumble, which in slang means food or a meal, often of reheated left-overs. There is also the adjective houndish. Food also gives the stodger, who is presumably more gourmand than gourmet. Alongside the dog, the pig: Sir Thomas Urquhart gave bacon-picker in his 1653 translation of Rabelais. Later one finds the oinker, and the simple pig, with pig out, pig in, piggy, piggish and the phrase to make a pig one oneself.

Using the same extended imagery as West India’s licky-licky one finds lickerish, never satisfied and wanting everything; especially in a gluttonous lust for food. The 16th century offers lick-dish (the lickfinger is the cook; thus John Taylor’s further comment on meatless Lent: ‘The goaring Spits are hang’d for fleshly sticking,/ And then Cookes fingers are not worth the licking.)

Yiddish brings the fresser, from fress, to eat (to nosh means only to snack and is rooted in German naschen, to nibble, to eat surreptitiously; it’s mainly American but those, like me, of certain age, may recall The Nosh Bar, a long lived salt beef paradise in Soho’s Great Windmill Street.) Gannet took off in the Royal Navy, and refers to the bird (itself linked to gander); it is defined in Bowen’s Sea Slang of 1929 as a ‘greedy seaman’ and crops up again in a dictionary of prison slang of 1950. Its locus classicus is perhaps in Ian Dury’s ‘Billericay Dickie’ in which one of the Essex lothario’s conquests, Janet from the isle of Thanet, ‘wasn’t ‘arf a gannet’. Although her appetite may have been for slang’s rather than standard English’s form of ‘eating’.

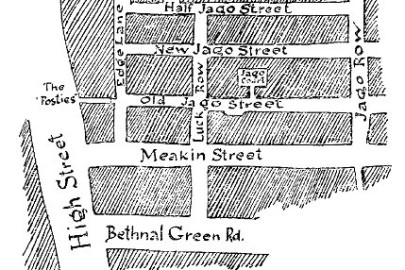

Finally, since one must never resist a pun, the early 17th century’s Hungarian. In the hack writer Samuel Rowlands’ poem ‘To a Gormandizing Glutton’ of 1613 one finds ‘A monstrous eater […] Invited was unto a gentleman, / Who long’d to see the same hungarian, And note his feeding.’ The play is of course on hungry, but also on the Hungarian freebooters, who once terrorised their neck of Europe.

Do you have a question for Mr Slang? Email it to editorial@thedabbler.co.uk and we’ll send it on to Jonathon.

Is it wrong that this post made me feel hungry?

I never knew that the root of Lent lies in a lengthening of days. From now on I shall take the word literally and quietly celebrate its commencement (can’t wait for this freezing winter to be over).

The post made me queazy – but then I did have a bacon cheeseburger and chips for lunch.

All this gorbellied gotch-gutted gourmandizing has put me in mind of something I used to love but haven’t looked into for years – Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel , in the 17th century translation by Sir Thomas Urquhart. In particular, there’s an extraordinary (and seasonally very apt) account of the war between Shrovetide (“a huge greedy-guts … banner-bearer to the fish-eating tribe, dictator of mustard-land”) and the Chitterlings of Wild Island. This comes with an almost Homeric catalogue of the heroically gluttonous cooks who serve in the conflict:

Sweet-meat. Greasy-slouch. Sop-in-pan. Greedy-gut. Fat-gut. Pick-fowl. Liquorice-chops. Bray-mortar. Mustard-pot. Soused-pork. Lick-sauce. Hog’s-haslet. Slap-sauce. Hog’s-foot. Chopped-phiz. Cock-broth. Hodge-podge. Gallimaufry. Slipslop … Pinch-lard. Snatch-lard. Nibble-lard. Top-lard. Gnaw-lard. Filch-lard. Pick-lard. Scrape-lard …Gulch-lard. Snap-lard. Rusty-lard. Eye-lard. Catch-lard … Porridge pot. Pick-sallat. Kitchen-stuff. Lick-dish. Broil-rasher. Verjuice. Salt-gullet. Coney-skin. Save-dripping. Snail-dresser. Dainty-chops … Soup-monger. Pie-wright. Scrape-turnip. Brewis-belly. Pudding-pan. Trivet. Chine-picker. Toss-pot. Monsieur Ragout. Suck-gravy. Mustard-sauce. Crack-pipkin … Scrape-pot. Skewer-maker. Swill-broth. Smell-smock. Rot-roast. Hog’s gullet. Fox-tail. Dish-clout … Save-suet. Spit-mutton. Old Grizzle. Fire-fumbler. Fritter-frier. Ruff-belly. Pillicock. Flesh-smith. Cram-gut. Strutting-tom. Prick-pride. Tuzzy-mussy. Slashed-snout … Loblolly. Sloven. Trencher-man. Slabber-chops. Swallow-pitcher.Goodman Goosecap.

Scum-pot. Wafer-monger. Munch-turnip. Gully-guts. Snap-gobbet. Pudding-bag. Rinse-pot. Scurvy-phiz. Pig-sticker. Drink-spiller … Man of dough. Lick-finger. Gurnard. Sauce-doctor. Tit-bit. Grumbling-gut. Waste-butter. Sauce-box. Alms-scrip. Shitbreech. All-fours. Taste-all. Thick-brawn. Whimwham.

Scrap-merchant. Tom T–d. Baste-roast. Belly-timberman. Mouldy-crust. Gaping-hoyden … Calf’s-pluck. Frig-palate. Red-herring. Leather-breeches. Powdering-tub. Cheesecake.

Superb. Thank you. Rabelais has wonderful lists and Urquhart sometimes coined new English terms to translate them. There is an equally glorious one – somewhat earlier – of synonyms for what his nurse terms Pantagruel’s ‘chitterling’.

I’ve always liked the (I guessing very formal and not at all slang) ‘trencherman’, which I’ve always felt ironically suggests that a certain WWI stoicism is required for this way of life.