Historian Dr Craig Fox has just published his first book, Everyday Klansfolk – a study of the extraordinary popularity of the Ku Klux Klan in mainstream midwest American culture in the 1920s. Here, he tells the story of how he came to research this forgotten phenomenon…

I was going to try very hard to keep my head down for the next twelve months.

Simple, eh? That was the fool idea I’d settled upon, and consequently just about the only plan I had going into this.

In hindsight, it seems no real surprise that said “plan” began to unravel almost as soon as I got off the plane. Clearly, I’d overestimated my own aptitude for pre-rehearsed cool reason and verbal eloquence, and it turned out that explaining anything at all to a frowning crew of post-9/11 US immigration officials was going to be tricky, let alone explaining this.

Okay, so I was going to be sticking around for about a year, maybe, and I wasn’t sure where, exactly, I’d be staying just yet, and in fact was “probably going to be moving around quite a bit.” Oh, yeah, and I was going to be doing as-yet unspecified “historical research” on the most notorious domestic US terror organization of modern times, the Ku Klux Klan.

Foreigner, huh? Seeking long-term entry to the land of the free, are we? In order specifically to sniff out well-known troublemakers and unflinching purveyors of racial hatred, you say? What should I put as purpose of visit, sir? White Supremacy Investigator? Not an easy sell in Detroit, that, believe me. So things weren’t going great, but hey: I was jetlagged, preternaturally nervous, and hideously garbled, explanation-wise. I figured that this is just what happens at customs, and at least I could fall back on my good looks to help me out of a tight spot. Oh, wait, I’d forgotten: thanks to Mother Nature’s largely giving up on my top-end follicles by the time I’d hit twenty, coupled with my sun-free northern upbringing, for years I’ve also looked to the untrained eye like every inch the pasty, twitchy skinhead. A cruel twist indeed when one’s stock-in-trade is the study of extreme right-wing nutjobs. It really doesn’t take one to know one. It just looks like it does.

Eventually, with that ordeal somehow navigated (the details are blurry, perhaps traumatic. Maybe they got tired of running rings around me and decided that a real terror threat couldn’t possibly be this bewildered all by himself), it was down to business proper.

The KKK I’d come to look at was the 1920s version, which, in many ways, had been both the least extreme and the most significant in American history. Sandwiched chronologically between the fanatical and racially violent Klan movements born at the end of the Civil War era and again in the wake of the Civil Rights era, the ‘Invisible Empire’ of the Jazz Age shared the infamous robes and regalia of its namesakes, but was an altogether different kind of beast. Rather than an overt reliance upon vigilantism, this ‘second’ Klan made wide-ranging popular appeals to Protestant morality, to law and order, to legal restriction of immigration, and to Prohibition enforcement.

Along the way, and in the context of a socially anxious postwar America, it achieved staggering support, boasting membership figures which dwarfed all other Klan movements before or since. With recruits numbering well into the millions by mid-decade, the KKK in the 1920s for the first time transcended the borders of the old South to attain widespread national prominence.

Surviving records are notoriously rare. They tend to be routinely destroyed either by members themselves, back in the day (as you might expect from any secret society worth its salt), or, failing that, by shamefaced relatives who came across the evidence in later years. In that respect I lucked out, having happened across reports of a new stash, found in the attic of a deceased Klan bookkeeper in the northern state of Michigan.

Following up on the records over subsequent months (by which I invariably mean gathering the dirt on dead ex-members from a scattering of very small, very local history collections), I’d constantly find myself getting busted via the medium of chipper, small-town curiosity. In grumpy old Britain, keeping self-to-self is easy. Head down. Look involved. Busy. Un-talk-to-able. People then give you exactly what your rude unsociability deserves, which is a wide berth, and certainly don’t ask the awkward, mortifying questions you’d been hoping desperately to avoid.

Not so here. Refreshing –endearing even– as it can be in almost any other context, the friendly, if inquisitive and rather insistent probings from current residents of my Klan-book’s historical setting just gave me the almighty willies.

“OMG. We don’t usually get visitors from out of the county, let alone Europe!” comes the kindly, giddy voice from the nice lady running this town’s (village. Let’s not kid ourselves) much-neglected local studies room.

“I’m so excited you’re here, I think I’ll make you the subject of this month’s newsletter! So tell me everything! Just what was it about our little town that brings you all this way to visit us? Oh, just hold it there while I take your picture, to go with my article…”

Right about now I’m noticing that the surname on her badge tag looks sort of familiar. Maybe from something I’ve read recently… Next I’m scrabbling to roughly discern her age, so that I can at least try and get it right when I have to tell her just which one of her immediate ancestors I’m implicating as a Kluxer… Then I’m trying to remember if I told anyone I was coming here, and wondering do I have enough bolts on my motel door? Why hadn’t I hired a car? Why the hell was there no bus service on the rural routes? Did the local railroad really have to fold decades back from lack of use? I’m freestyling unlikely escape plans. I’m thinking cover of darkness, and distances to county lines…

“Um, nothing too exciting. Local membership of … erm … fraternal organizations … after the war… Masons, Odd Fellows, Rotary clubs … that sort of thing,” I cluck out, chicken-like. Shamefully. Ungracefully. Unconvincingly.

Not that anyone had much to fear from my study anyway. In fact, the gist of the thing was not so much to point the finger at Klan abhorrence and bigotry in this age (though there was still plenty of that flying around, in a largely anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant form), but rather to explore the organization’s sheer size, spread, and relative normality in American cities and small-towns alike.

It turns out that, within the (often isolated, overwhelmingly white and Protestant) communities where the KKK took hold in the twenties, just about every kind of people became members. Labourers, merchants, farmers, bankers, policemen, schoolteachers, housewives, barbers, insurance men, doctors, dentists, blacksmiths, judges and clergymen. Butchers, bakers, candlestick makers. You get the idea. Every occupation was represented, as were all ages and both sexes, recruited at work, in the lodges, or through family. Men, women, and children; the rich and the poor; even the right kind of immigrant (the white Protestant kind) was given a go if he made the right pledges.

I found Klan connections in the most bizarre and inappropriate of places. My prying through four years’ worth of love letters between a Detroit postman and his schoolteacher missus-to-be, for example, revealed a romance peppered with the white pointy stuff. In one exchange, our postie insists on keeping one night a week “private” and off-limits to ’er indoors. His intended –understandably hurt, confused, and heavily suspecting infidelity– issues an ultimatum. As is customary in such circumstances, this brings about a full and immediate crumbling on his part.

“Guess I’ll have to tell you about my Tuesday night goings on,” he writes dolefully, denying playing away, but admitting instead to regularly attending hooded gatherings down the local dance hall. “They have changed their meeting night recently and have some home talent entertainment afterwards. I like that kind of entertainment … so that is where I’ve been.”

Rather than sending her running for the hills, it seems these words of charm have done the trick. “I feel some better since reading about your Tuesday night escapades,” writes a relieved Mrs. postie, her faith restored. “Why under the sun didn’t you tell me that in the first place? I know I never would have thought anything of it. What difference would it make to me if you were at a Klan meeting or at a show?”

Okay then.

Now, it might look weird from where we stand, but in its time and place this kind of scenario really was nothing out of the ordinary. The twenties Klan strove for a mainstream audience, and it did so by incorporating what were otherwise very routine activities and leisure pursuits under the KKK banner.

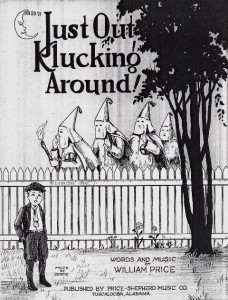

Many prominent local ministers, for instance, not only openly endorsed the Invisible Empire in Sunday services, but often conducted public christenings, weddings, and funerals under its auspices, doing much to normalize its presence in community life. In this altered world, white-robed brass bands, singers, vaudeville acts, children’s auxiliaries and sports teams abound, basking in the pageantry and ready-made sociability of huge regional Klan parades, picnics and potluck celebrations. Likewise came Klan movies, stage shows, fireworks, jewellery, household ornaments, crossword puzzles, even holiday resorts.

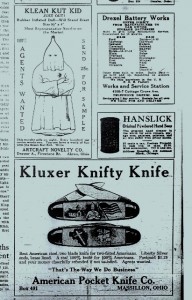

The men in white emphatically embraced an emergent consumer culture, made prominent links with business, and never missed a trick on the merchandising front. Robes and paraphernalia were mass-produced in factories, and gimmicky, KKK-themed advertising surrounded the movement at every turn.

Don’t get me wrong: the result of all my digging is every inch a serious book, about an often baffling period in American history. Having said that, it’s certainly worth noting that a voice as astute as H. L. Mencken maintained throughout that this was by nature a preposterous organization, populated en masse by the kind of “boobs” and “knuckleheads” who could be sold just about anything. In fairness to that point of view, and without going so far as wholehearted agreement, I’d say you wouldn’t be human if you were able to suppress your snickering at some of the more ludicrous detail.

You like music, son? You’re after a record, you say? How about Daddy Swiped the Last Clean Sheet and Joined the Ku Klux Klan? A red-blooded adventure novel, young man? Sure. Try Harold the Klansman for size. And something to keep the little’uns happy? Why, the inflatable rubber Klan doll, of course…

Oh, and want to mark that special occasion with all your mates, out in the woods of a night, perhaps? Then try one of our patented “Fiery crosses, in any size up to six feet.”

I ask you.

where did the ‘Ku Klux’ bit of their name come from I wonder? I do find all this sort of shadowy mason type stuff fascinating; the way that these small towns can have a sort of underground league of prominent townsfolk all getting up to shady things

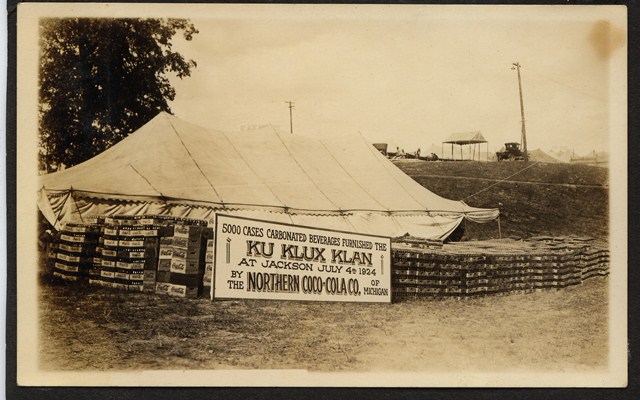

I confess I’m a bit nervous about publishing the pic at the top of this post.

“5000 carbonated beverages furnished the Ku Klux Klan.. by the Northern Coco-Cola Co. of Michigan”.

Don’t suppose Coke still boast about that one… The men in black (or perhaps white?) could be knocking at the door of Dabbler Towers any minute…

The photo at the top of the post is almost worth a post in its own right. What’s going on there?

Presumably, from reading the sign, we’re in Jackson, Mississippi, celebrating the 4th of July at some point early in the 20th century. But it’s worth remembering that for many of the men and women doing the ‘celebrating’, the catastrophe of the Civil War would have been a relatively recent memory – perhaps no more far away from them than the events of the late 1960s or early 1970s are to us today – to whom it would have been obvious that the Union being feted had been held together at the cost of some 620,000 lives, the majority of those from the South. Unsurprisingly, not every Southern community found much to celebrate on the 4th of July until the Second World War or thereabouts – certainly, within my own living memory, I distinctly recall some of my North Carolina neighbours being fairly ambivalent about it.

So that’s all rather odd. But odd, too, is the branding. Why make such a big deal out of the fact that the Coca Cola in question was bottled in Michigan, when Coca Cola is famously a Georgia-based company, and I think always was?

So along with all the other more obvious oddities evoked well in the actual blog post, one can’t quite avoid wondering whether there is some sort of hearts-and-minds campaign being waged by a would-be national brand, to somehow encourage the KKK further inside the big tent of all-American cultural identity, through the blandishments of their syrupy-sweet cordial.

It’s all slightly reminiscent, indeed, of those later ‘I’d like to teach the world to sing …’ adverts of theirs from the 1970s, so redolent now of long-haired girls and shorn-headed conscripts, the ground floor windows of the federal buildings in my North Carolina home town all bricked up because of the riots, desegregation, the smell of cannabis and tear gas, grainy television images of body bags being repatriated, urban terrorism, assassinations.

Ah, the implicit politics of Coca Cola! I suspect they mean well, really. It’s hard to get American politics right at the best of times.

Note the spelling ‘coco-cola’ (not ‘coca-cola’). Could it be an imitator?

Barendina, forgive me, I may have missed an important point in this post and your comment. You presume that the old photo was taken in Jackson at a point in the early years of the 20th century, but the Coco Cola banner states 1924. If this is correct, and bearing in mind that life expectancy in 1920s America was around 60, the Civil War would not have been a relatively recent memory for those present in 1924. Would the fact that the war had occured 60 rather than 40 years before go some way towards explaining the apparent embrace of the Union?

Sorry, John – I missed the 1924 on the sign. But my point about the Civil War does, to a degree, still stand. What I am suggesting is, if you think of it, no odder than thinking that some people today might have views of Germany, Japan etc coloured by events either of their own early childhoods or by what they had heard from their parents’ generation. And it is absolutely the case that many people in the South didn’t celebrate the 4th of July until the Second World War produced an alternative set of war-related national memories.

When a population of c 31.4 million loses 620,000 men over four years, it’s traumatic – all the more so when the ‘enemy’ was so close to home. So it’s interesting both that anyone in Jackson wanted to celebrate the Union – and that Coca Cola was evidently glad to associate itself with such celebration.

Anyway, sorry to footnote this excellent post with so much Civil War related morbidity!

Hmm. There certainly was a Coca Cola bottling plant in Grand Rapids, Michigan by the early 1920s, so I am tempted to attribute that odd spelling to Southern, ahem, creativity in matters of spelling. (And before y’all Jackson folk git out yer shotguns, I should add that of all the various Southern forms of more or less self-conscious atativism, a refusal to embrace codified spellings is by no means the least endearing.)

Note that spelling of ‘atavism’ above – you can take the girl out of the South, but … [etc.]

Hello all –

First time here, so please go gentle…

Worm – ‘Ku Klux’ is a mangling of the Greek word ‘kuklos,’ meaning ‘circle’. And you’re right: It’s shadowy, Masonic, mumbo jumbo dreamed up by the original, post-Civil War version of the Klan. You’re either in the circle or you’re out of it, I guess.

And Barendina, John- Just a clarification on the time and place: This is indeed 1924, and we’re in Jackson, Michigan, rather than Mississippi. I’m not sure anyone was thinking too hard about the Civil War here. Having said that, there was as least one prominent southerner in the mix. Keynote speaker, Imperial Wizard and Atlanta dentist Hiram Evans had been shipped in from Georgia for the weekend…

Oh, that’s the answer, then – Michigan! Sorry again – learn something new every day, eh?

I really enjoyed this Craig – writing typical of Jonathan Raban at his best, and I’m ordering the book. No other comment, as it’s not my place/period, save to say what won’t surprise you: the Michigan wing of my family were on the wrong side of the Civil War, and it’s very much a live dispute insofar as they are concerned (going as far as involvement in the Daughters of the Confederacy and the Confederate Air Force, to name but two of their many involvements in keeping the, er, flame, alive. Sixty years? Shmixty!

Great post, fascinating pictures too.

I think with the growth of certain populist movements as we currently have in the US, investigating the Second Klan seems particularly apposite. I’ll have to purchase a copy.

Watched “Birth of a Nation” for the first time a few months back and was repulsed, but also disturbingly compelled by it too. I can certainly understand how in others – if it chimed with them politically – it might inspire them to establish such an organization, as well as also becoming a great recruiting tool in the years to follow.

The cutesiness is the scariest bit.

I seem to remember Arthur Conan Doyle in one of his books claiming that the name ‘Ku Klux Klan’ derived from the sound made loading and locking a rifle. Not so?

I think Conan Doyle mentioned that in ‘The Five Orange Pips’, though as far as I know he’s using a bit of artistic license there, and it’s a duffer in terms of an origin tale. That said, it’s doubtless much more atmospheric than the Greek fraternity stuff, and has probably been used a million times since by blokes in pointy hoods who like to terrify people.