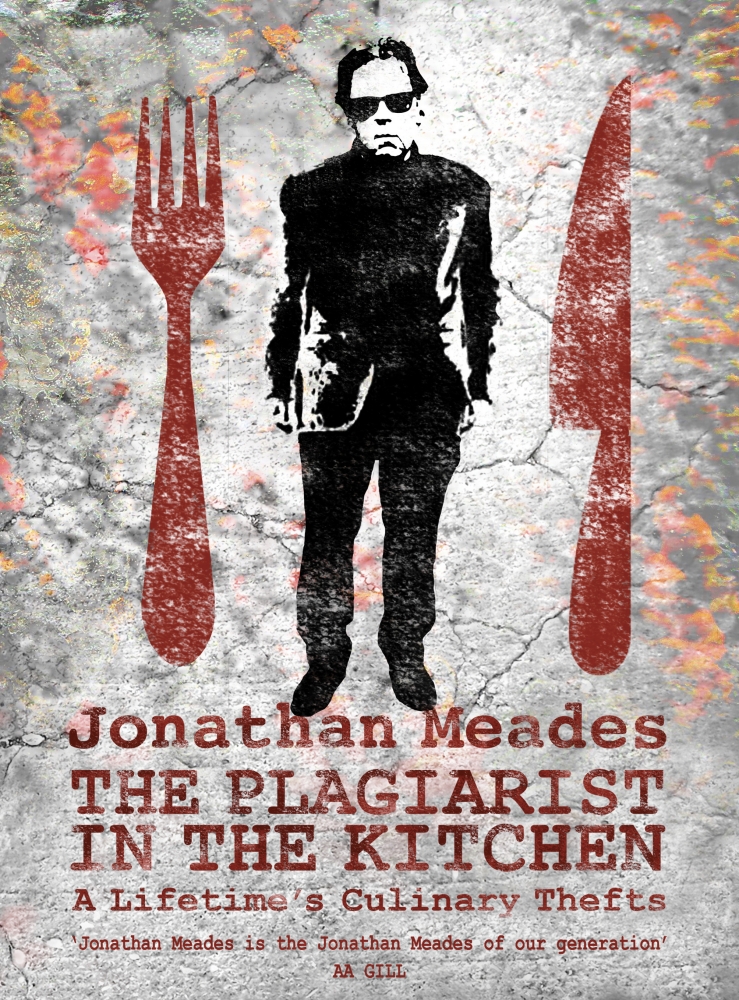

Brit reviews the superb new ‘anti-cookbook’ from the mighty Jonathan Meades…

The first thing I do with a cookbook is have a quick flick through to assess how effortful is the gist. On opening The Plagiarist in the Kitchen I found:

To kill an eel you need a brick and a concrete surface. Hit it on the head. Then hit it again. To skin it, nail it by what remains of its head to a rough wooden work surface. Cut round the skin then make incisions to loosen the skin. This should allow you to grip the skin with the aid of a cloth or gardening glove and pull it off. Should allow you: it’s not a straightforward process, bear with it.

Once you have removed the skin make a slit from head to tail in order to eviscerate it. Easy enough if you’re not squeamish. I should point out that no matter how thoroughly you’ve bashed its head in – think here of old Phillip Mathers – the eel is going to be wriggling in its posthumous throes.

Ah.

But on the other hand I skipped back a bit and found this recipe, which I quote here in its entirety:

GRILLED MACKEREL

Mackerel

The fish must be extremely fresh. It needs 4-5 minutes each side on/under a very hot grill. Do not add any sort of sauce. Just salt.

Now that’s more my sort of level. In the end I decided to have a crack at a recipe between those two poles of effortfulness: salmon with a tapenade crust. I’ll come on to that later.

What is The Plagiarist in the Kitchen? It is three things: a practical cookbook; a polemic against other cookbooks and many elements of today’s foodie business; and finally it is a Jonathan Meades book. That is, the latest addition to the Meades-canon, which means it could be in almost any genre (architecture, cultural history, fiction, memoir) but must possess an essential quality of Meadesiness so that it meets the needs of its very particular constituency (Meades-fans, who’ll receive anything Meadesish that Meades chooses to emit).

On all three counts it scores highly. In fact it knocks it outta the park. As a cookbook it is comprehensive, covering everything from basic stocks to desserts and cheese, yet focused and follow-able and very practical. The cheese soufflé recipe includes this advice: ‘Separate the eggs. If you fuck up do not chance it by including broken yolk in the albumen, it’ll prevent it stiffening.’

It sticks to European grub of the north, south and mittel (no curries or jerks etc) and has that very pleasing ‘only-cookbook-you’ll-ever-need’ feel. It offers certainty, which is important in recipe books. Jonathan Meades, as we know, does not lack confidence in his opinions (I wish I was as cocksure about any one thing as Jonathan Meades is about everything, as Lord Melbourne said of Tom Macauley… Or was it the other way about? Meades would know) and he gives it to us straight. ‘French black puddings that include chestnuts are worth avoiding. Those that include piment d’Espelette are to be sought.’ That sort of thing.

As for the polemic, the thesis is that good cooking necessarily involves stealing the proven recipes of others, especially those of the greatest chef of all, ‘Anon.’ The wheel, Meades says, has already been invented. The best ways of turning tomatoes into sauces or combining potatoes, anchovies and cream into dishes of deliciousness have long been known, so there’s no point trying to reinvent them. This is not the same as seeking ‘authenticity’. Always go for good over authentic, he commands. Cooks may improve and customise the work of previous cooks (usually removing extraneous ingredients) but they should remain plagiarists – or craftsmen – and not pretend to be artists. ‘Never enter a restaurant that advertises its “cuisine d’auteur” or “creative cooking”.’

Meades’ argument is delivered via notes and digressions dotted through the text, and I confess the distinction between ‘improving’ (permitted) and ‘creating’ (not) was a bit unclear to me until I came to the recipe for Fig and Ham Tart, which contains these instructions: ‘Leave to cool. Taste. Chuck in bin.’ Meades includes the inedible tart as a warning. It is a dish he tried to invent, ignoring his own prescription ‘Never create when you can steal’. Otherwise you can end up with Aubrey’s restaurant menu from Mike Leigh’s Life is Sweet: ‘Black pudding and camembert soup, Saveloy on a Bed of Lychees, Liver in Lager, Pork Cyst, King Prawn (just one) in Jam Sauce’ etc.

Nothing needs a twist…The best a cook can do is improve on what’s there…. It means going back to the very foundations, of starting from zero in order to reach a point that has been reached many times before.

I’m convinced, anyway.

And what of the third thing, the Meadesiness of the book? Well yes, it has everything a Meadesman could wish for. Meaty, chewy prose. Plentiful pungent asides. Irrelevant abstract ‘illustrations’ add nothing except a dim sense of unease. On page 119 a fatuous and incongruous swipe at the Christian doctrine of the eucharist floats like a glob of Richard Dawkins’ spit in a risotto. All good, bracing stuff, but don’t let these obligatory Meadesian motifs fool you. The Plagiarist in the Kitchen is an incredibly generous book. It is a gift to the world from a man who has spent decades getting to know food better than nearly anyone else.

I made the salmon dish – cooked as per Meades’ instructions for a mere 8 minutes in a very hot oven – and it was quite extraordinarily delicious. The remainder of the garlicky, oily, perfectly sublime tapenade I funnelled into a jar and have been spreading it on every breadstuff I can lay my hands on since. My life has thus already been markedly improved by this book. Buy this book.

The Plagiarist in the Kitchen is available from Unbound here.