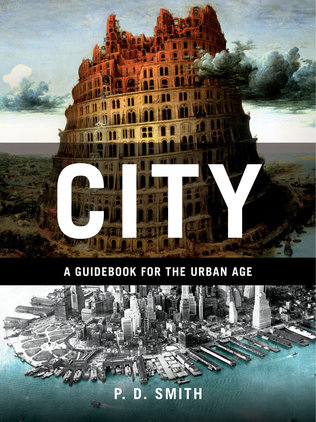

For the first time in history, more than half the population – 3.3 billion people – is now living in cities. Elberry reviews ‘the ultimate guidebook to our urban centres’…

From the sky, England still looks green. On the ground, it’s another story, all cancerous conurbations and serial ghettos. Most people live in a totally urban environment, where parks are an arena for jogging, rape, gang warfare, and drug use. Even small villages are really just the furthest ejaculate of the city, and bear the same spores – hooded youths swarming about the Tesco Express, chugging Mad Dog 20-20 and generally acting gangsta.

One could be forgiven for wishing extermination upon the brutes. And yet, not all cities are so; get out of England and one can find, for example, Munich – a large, prosperous, almost crime-free city. Smith’s book doesn’t look closely at why cities fail but is nonetheless interesting, as a wide-ranging survey of urban populations.

City is a mix of statistics, anecdotes, and occasional declarations. It opens:

Cities are our greatest creation. They embody our ability to imagine how the world might be and to realise those dreams in brick, steel, concrete and glass. Today, for the first time in the history of the planet, more than half the population – 3.3 billion people – are city dwellers. Two hundred years ago only 3 per cent of the world’s population lived in cities, a figure that has remained fairly stable (give or take the occasional epidemic) for the last thousand years. By 2050, 75 per cent will be urbanites.

Birmingham and Sunderland are cities: are they then among our greatest creations? – greater than Mozart’s Don Giovanni? And is it legitimate to say cities “embody our ability to imagine how the world might be”, given that so many just unpredictably and chaotically sprawl? If anything, the desire to “imagine how the world might be and to realise those dreams in brick, steel, concrete and glass” is nothing to cherish. As Smith notes of Le Corbusier:

[…] it is striking that throughout the twentieth century the idealism of architects and planners about the urban future has been – and, indeed, continues to be – opposed by the deep pessimism of most writers and filmmakers. Time and again, architects offer seductive glimpses of glittering skyscrapers full of hothouse vegetation or sentient cities that satisfy every whim of their inhabitants, while novels and films conjure up visions of alienating cities in which people are reduced to cogs in a dehumanising urban machine.

With cities comes traffic. New York:

By 1890 (when lines were being electrified), nearly eight hundred companies operated more than 32,000 streetcars on six thousand miles of tracks. They carried some two billion passengers, twice as many as in the rest of the world combined. Unsurprisingly, the streetcars were all overcrowded. ‘People are packed into them like sardines in a box, with perspiration for oil,’ complained one commuter in 1864.

New Yorkers spent more than two hours each day commuting. The streets were jammed with traffic and if the sidewalks hadn’t been equally packed it would have been quicker to walk.

As a natural reaction, the suburbs:

Downtown’s loss was suburbia’s gain. For this was the beginning of America’s love affair with suburbia, the dream of a semi-rural bourgeois utopia. For the middle classes this meant a single-family home surrounded by trees and a white picket fence.

However, it was not always so. i was excited to learn:

London’s suburbs were infamous places of lawlessness, full of ‘base tenements’ and noxious industries, such as soap-making and tanning. The author of a sixteenth-century guide to the capital alluded to their sleazy reputation when he asked: ‘London, what are thy Suburbes but licensed Stewes?’

In general, people want a quiet place to live, but with easy access to shops and work, and preferably without too much violent crime. For most of the time, that has meant the suburbs. The city has usually been a centre of crime and filth; even the most glamorous:

A seventeenth-century guidebook claimed that ‘filth in the streets and traffic have made it impossible to go about in Paris except in coach.’ The streets of Paris were, indeed, famously filthy and the mud that coated every street was notorious. Known as ‘la boue de Paris’, one visitor described it as ‘a black unctuous Oil’. The truth was that Parisian streets were effectively open sewers and if you wanted to keep your fine gown or shoes clean, you needed to be physically carried from door to door.

I can almost smell the garlic. It seems that any concentration of human beings will lead to dangerous accumulations, for example traffic:

In São Paolo, where there are nearly seven million registered cars, traffic jams can stretch for 100 miles (160 kilometres) at rush hour. In China – the country that holds the record for road deaths (110,000 a year) – a traffic jam in Beijing took police three days and two nights to unblock.

Just under 1.3 million people die on the roads every year, worldwide, one of the benefits of technology and the modern world. However, humanity is fighting back, for example in Bogotá:

Thanks to the policies of mayors Antanas Mockus and Enrique Peñalosa, who ran the city from 1995 to 2003, the number of deaths from traffic accidents in Bogotá has been almost halved, falling from 914 fatalities in 1998 to 553 in 2006. Mayor Mockus even employed mime artists to draw attention to bad driving. The sight of mime artists pretending to pull vehicles that were dangerously parked became common on Bogotá’s streets.

At this point, one feels the need for an entire book on the social benefits of mime. This is the problem with Smith’s book, that in covering so much it must perforce be superficial. It will probably irritate a specialist but as a general, entertaining work it is very well done.

Birmingham has to be the crappest city in the world

It is the only city i’ve visited where you feel liable to be mugged at 2 pm in the city centre. i put on my killing mask and kept it firmly in place on my last Birmingham jaunt.

Incidentally, Tolkien was raised in the suburbs of Birmingham when it was largely rural. At the end of his life he said that England had changed more between his birth (1892) and the present (early 1970s) than between his birth and Shakespeare’s time.

A slight quibble about the suburbs, at least the North American ones, and the reasons people flock to them. It’s superficial to talk of white picket fences and bourgois utopias, although that dovetails nicely with the traditional sniffy dismissals of leftists, aesthetes and the horsey set. People move to the suburbs to nest. The focus of everything is the kids, who don’t normally evince a lot of cravings for fusion cuisine and repertory theatre. Suburbs are all about healthy convenience during life’s most stressful years, private bedrooms, good schools, safe streets, recreation opportunities and lots of other kids. It’s family duty and priority that drives their growth, not a philistinie penchant for bland uniformity.

A secondary reason, especially among immigrants, is to put some distance between young people and those extended families that are always being romanticized by people who don’t have one.

One assumes elberry, that your infatuation with Sunderland has finally gone to that great urban planning department in the sky. Your description of our sceptred isle outwith the metropolis (metropoli?) sounds like Wensleydale during the school holidays and in any case an odd yardstick or two would not be out of place here, try driving from Katowice to the Ukrainian border in mid January, a Blade Runnerfest as ever was.

As a lifelong Brummie I suppose I shouldn’t be shocked at the way people react to the place, but the level of fear that seems to haunt the middle class english imagination never fails to surprise me.

Personally I don’t find Birmingham scary, I just find it amorphous and dirty beige

Birmingham’s only downside is it’s proximity to Coventry. The town that time mislaid. Talking of mislaid, anyone noticed the new buzzy word creeping into the media misremembered

I like Brum. I lived in and around Stirchley for a year and had a great time. The friendly people and the baltis stand out. And you could get to the beautiful Warwickshire countryside in fifteen minutes when you wanted a break.

Mind you, the air practically crackled with latent violence at about 10.30 on a Saturday night on New Street, more so than anywhere else I can recall.

Suburbs: the 16th century London suburbs you note, with their crime and sink industries, were not today’s leafy (if soulless) outer fringes, as in America’s ‘burbs, but places such as Clerkenwell (EC1) which existed immediately outside the city walls and as such were not subject to laws against, inter alia, prostitution, that controlled life within. Turnmill Street, of which I have posted, was a typical ‘suburban’ neighbourhood. Such areas are now, of course, what is known as ‘the centre’.