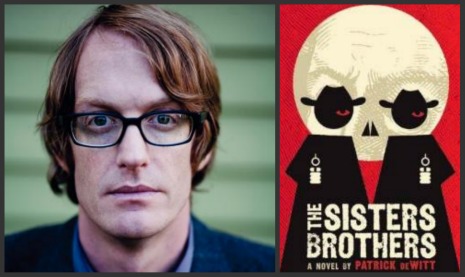

At The Dabbler we’re going to be reviewing more of the best new books, both recent publications and imminent ones. Here Elberry takes on The Sisters Brothers – one of the shortlisted books for the 2011 Man Booker prize – and explains why its protagonists would “brutally and justly pistol-whip Ian McEwan”…

If there was ever anyone who could find a way to kill himself with an ax, it was Father.

So speaks a deranged chemist in Patrick deWitt’s Hooting Yard Western, The Sisters Brothers (Granta); his audience: Charlie and Eli Sisters, brothers and professional killers in a West still Wild enough to feature marauding Indians and bears and whores, the latter most perilous. The book is told by Eli, the gentler, hairier, fatter, altogether less stylish of the two. Charlie is the cool hand, the killer, the duke; Eli is one of those portly bearded hard men, shy and unnatural with women, leaving them large sums of money if they so much as talk to him. His narration is half-awkward, half-eloquent, in the best American tradition. Everyone speaks so, in a voice both untutored and powerful – untutored, one may say, save for the Bible:

He did not notice my leaving, I do not think, preoccupied as he was with his vomiting and unwellness.

The obvious literary forebear is Cormac McCarthy; a useful contrast. DeWitt is much lighter, so even his quite frequent brutalities are untroubling, leave no mark; he does not harrow. This is not to criticise deWitt – he is doing something different to McCarthy; and whereas humour is occasional and incidental in McCarthy, it is central in The Sisters Brothers; and the novel is something of a commedia in Dante’s sense of the word: there is a relatively happy ending, and it feels just. Humour, of the warped Frank Key variety, is a mode of perception in this novel. It is perhaps natural to the frontier, that one can only survive horrors if one can apprehend and contain them, and humour is one way, a circle drawn about death and pain. As the Sisters brothers shoot, beat, drink, and talk their way through a landscape of small-town barons, rival gunslingers, and uppity beavers, they encounter many scenes of violence; they respond with appropriately laconic humour. So, trapped by a gang of over-confident and extravagantly-hatted trappers:

…Charlie paused behind a tall sign to watch the largest trapper leaning against a hitching point below us. Now the other three joined him, and the group stood in a loose circle, speaking through their dirty beards. ‘Doubtless they are infamous among the muskrat community hereabouts,’ said Charlie. ‘But these are not killers of men.’

And later, as the trappers have them cold, four against two:

‘I am going to shoot you down,’ said the trapper.

‘My brother will count it out,’ said Charlie. ‘When he reaches three, we draw.’

The trapper nodded and returned his pistol to his holster. ‘He can count to one hundred if it suits you,’ he said, opening and closing his hand to stretch it.

Charlie made a sour face. ‘What a stupid thing to say. Think of something else besides that. A man wants his last words to be respectable.’

‘I will be speaking all though this day and into the night. I will tell my grandchildren of the time I killed the famous Sisters brothers.’

‘That at least makes some sense. Also it will serve as a humorous footnote.’

The humour is not a means of denying the violence; it is a way of humanly apprehending it. The whole novel can be taken as a humorous excursion; or as an exploration of violence and the need or desire for love, through Eli’s difficultly loyal feelings for his lethal brother, and his schoolboy-like encounters with women, whores or not. The brothers seek gold and find it is a poisoned treasure, that no one comes to such wealth unharmed. It is a commedia of sorts but sufficiently strange and understated that one can take it as an enjoyably violent romp or something more, according to whim.

It is superior to any so-called “literary fiction” set in London featuring upper middle-class couples in marital difficulties, tempted by younger colleagues in the publishing industry, holidaying in Tuscany, sipping Chardonay and champagane, talking earnestly about poverty and pollution and equality. The Sisters brothers drink brandy and a lot of it; they don’t go on holidays; they consort with harlots; they would brutally and justly pistol-whip Ian McEwan and indeed anyone who works in an office, were the opportunity to present itself; and it is a good book and should be read therefore.

Great review. Interesting to imagine what one author’s characters would do if presented with a rival author. One feels certain that in the vast majority of cases fictional characters would prevail over the mostly weedy authors. Potentially a HootingYardesque situation.

Or indeed a Flann O’Brienesque one: as far as I can remember anything about the plot of At Swim-Two-Birds, it seemed to involve a bunch of characters from a cowboy novel tracking down and punishing their creator, as revenge for the various scrapes and ordeals he’d put them through.

Your review has made me want to read the book elberry, I’m imagining Carey’s Ned Kelly by way of Flann O’Brien and Magnus Mill’s Restraint of Beasts, which is good

Great review – just read it myself and liked it a lot – although I reserve the right to like Ian McEwan too – well sometimes.

My own review is on the blog for anyone who wishes to compare/contrast (but then, why would anyone really?)

AliB