Unwanted house guests, drugs and procrastination are the subject of this week’s foray into the nether regions of Wikipedia…

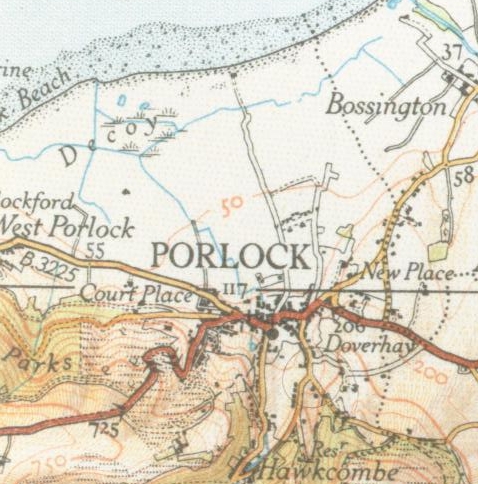

The Person from Porlock was an unwelcome visitor to Samuel Taylor Coleridge during his composition of the poem Kubla Khan in 1797. Coleridge claimed to have perceived the entire course of the poem in a dream (possibly an opium-induced haze), but was interrupted by this visitor from Porlock (a village near Exmoor) while in the process of writing it. Kubla Khan, only 54 lines long, was never completed. Thus “Person from Porlock”, “Man from Porlock”, or just “Porlock” are literary allusions to unwanted intruders who disrupt inspired creativity. The intruder in this case is purported to have been a local needing a horse to help pull the Lifeboat Louisa across land to launch after a storm had made Lynmouth inaccessible.

Coleridge was living at Nether Stowey (a village in the foothills of the Quantocks). It is unclear whether the interruption took place at Culbone Parsonage or at Ash Farm. He described the incident in his first publication of the poem:

“On awakening he appeared to himself to have a distinct recollection of the whole, and taking his pen, ink, and paper, instantly and eagerly wrote down the lines that are here preserved. At this moment he was unfortunately called out by a person on business from Porlock, and detained by him above an hour, and on his return to his room, found, to his no small surprise and mortification, that though he still retained some vague and dim recollection of the general purport of the vision, yet, with the exception of some eight or ten scattered lines and images, all the rest had passed away like the images on the surface of a stream into which a stone has been cast, but, alas! without the after restoration of the latter!”

English poet and essayist Thomas De Quincey speculated, in his own Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, that the mysterious figure was Coleridge’s physician, Dr. P. Aaron Potter, who regularly supplied the poet with laudanum.

This story is by no means universally accepted by scholars. It has been suggested that this prologue, as well as the Person from Porlock, was fictional and intended as a credible explanation of the poem’s seemingly fragmentary state as published. The poet Stevie Smith also suggested this view in one of her own poems, saying “the truth I think, he was already stuck”.

If the Porlock interruption was a fiction, it would parallel the famous “letter from a friend” that interrupts Chapter XIII of Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria just as he was beginning a hundred-page exposition of the nature of the imagination. It was admitted much later that the “friend” was the author himself. In that case, the invented letter solved the problem that Coleridge found little receptiveness for his philosophy in the England of that time.

Robert Graves wrote a short poem, “The Person from Porlock”, suggesting that more than a few other works would have gained from the same treatment.You can hear Graves read it it at about 22:27 of the first reading (second recording) at http://library.buffalo.edu/robertgraves/audio/ .

thanks George – it would appear from the ‘in other literature’ entries at the bottom of the wikipedia article that plenty of famous authors have riffed on the subject – including Conan Doyle, Nabokov and Douglas Adams

The following bagatelle appeared on Hooting Yard ten long years ago:

Like Samuel Taylor Coleridge, I know the misery of being inconvenienced by a person from Porlock. It happened thus. It was a Wednesday, I recall, teeming with Hooting Yard’s most tremendous rainfall for forty years. I was sat at the kitchen table attempting to insert a new pair of laces into my gleaming big black leather boots. Minnie was at her spinet, as usual, idly tinkling. I suspected that soon the tinkling would cease and she would launch into an impassioned performance of one of her ten thousand and twenty-two songs. I hoped she would play my favourite, the “Anthem for a Brutish Haberdasher”, or perhaps her mangled sea shanty “Bring Me Your Winding Sheet, O Mother of Mine”. As I fiddled ineptly with the laces, our door crashed open and a hirsute and drenched individual burst into the room. In an instant, a puddle formed at his feet. Minnie continued to tinkle.

“I come,” announced the stranger, in a declamatory roar as if he were addressing a vast crowd of huddled petitioners, “I come not from haunts of coot and hern. Nor do I come in response to your whistle, my lad.”

“I was not whistling,” I replied.

“Precisely!” he continued, “I come from Porlock, and I am going to confiscate your aglets.”

So saying, he withdrew from the pocket of his bright yellow windcheater a pair of garden secateurs, swiftly cut the aglets off the ends of my brand new laces, and charged out into the downpour. He did not close the door behind him. I held my head in my hands and began to weep. Minnie played the pounding opening chords of “Dismal Corncrakes”.

excellent Frank – as soon as I read the wikipedia page I thought it was very ‘Key-esque’. Incidentally the other day I was musing that should you ever need a title for an album, you could call it ‘Songs in the life of Key’

My favourite theory about the identity of the Person is that he was none other than Fletcher Christian, the celebrated mutineer, who is presumed to have made a secret return to Britain in the 1790s and to have come under the protection of the radical poets Wordsworth and Coleridge. The theory was first proposed by someone called C.S. Wilkinson in his book The Wake of the Bounty (1950s) and it has inspired several fictional works (including a recent-ish novel by Val McDermid). The evidence, such as it is, goes like this:

1/ A tradition that Christian had made a secret return from Pitcairn Island was established by 1810 at the latest. Several people who knew him well claimed to have spotted him in the West Country and later in the Lake District (the favourite stamping grounds of our two poets).

2/ Wordsworth unquestionably knew Fletcher Christian. The two men were related, albeit distantly, and they had been at school together in the early 1780s. What more natural than that the fugitive mutineer should have thrown himself on the mercy of his relative and school friend?

3/ A further link is provided by Fletcher’s brother, Edward Christian. A lawyer, Edward not only defended his brother from the mutiny charge (in absentia), but also acted for the near-penniless Wordsworth in his long-running suit against the Earl of Lonsdale — a powerful landowner who had effectively swindled the poet out of his inheritance. What more natural than that he should call in the favour by asking Wordsworth to protect his errant brother?

4/ Both Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1797-8) and Wordsworth’s disturbingly strange verse play The Borderers (1796-7) are known to draw on aspects of the Fletcher Christian story. Strong evidence, surely, that they had heard him relate his adventures at first hand.

5/ In 1796 Wordsworth wrote to a newspaper — the only occasion on which he is known to have done so — denouncing a recent book that claimed to give Christian’s own account of his post-Bounty adventures. Wordsworth stated that he had it on “the best possible authority” that this claim was entirely fraudulent. Note that Wordsworth — who took great pride in expressing himself accurately — does not say “good authority” or even “very good authority” but “the best possible authority”: what can this mean other than that he had spoken to Christian himself? And as to why he would write a letter publicizing his own role in harbouring a criminal fugitive, thereby endangering both of them — isn’t that just the sort of thing you’d expect from an idealistic young poet with his head full of French Revolutionary nonsense?

QED I reckon.

Yet again Jonathan your comment deserves a post of its own!