In an exclusive article for Bath Ales newsletter subscribers, Brit examines some famous literary pubs…

“Can I draw you a beer, Norm?”

“No, I know what they look like. Just pour me one.”

Thus Norm Peterson, entering the Cheers bar with one of his famous one-liners. (Other good Norm-isms from the long-running US sitcom include “How’s a beer sound, Norm?” “I dunno. I usually finish them before they get a word in” and “What’s shaking, Norm?” “All four cheeks and a couple of chins.”)

The pub is the perfect setting for a sitcom. It’s a public place, so there’s scope for a steady flow of new characters (or targets for witticisms). There are rules, mostly involving the landlord/customer relationship, but the pub is also a place of unusual freedom of speech and – given that all you have to do in a bar is sit around, drink and crack wise – plenty of opportunity to exercise it to the full. Above all, there are the regulars: the local clique with its catchphrases, running gags and complex interpersonal entanglements.

Regulars, for landlords, must be a bit of a double-edged sword. They keep the place going financially and create the atmosphere, but they can also intimidate the more casual pub-goer. Norm, Frasier Crane and the other Cheers drinkers were a relatively genial bunch, but in real life there have been a number of bars where ordering a drink in view of the locals must have been like entering the lions’ den.

Take the bar at the Algonquin Hotel, New York, where in the 1920s a gang of wits and wise-asses including Harpo Marx, playwright George S Kaufman and author Edna Ferber used to congregate, presided over by Dorothy Parker. They were known collectively as the Algonquin Round Table in society gossip columns, but referred to themselves as the Vicious Circle, which, given that Parker’s soundbites include (of Katherine Hepburn’s acting) “She runs the gamut of emotions from A to B” and “If all the girls who attended the Yale prom were laid end to end, I wouldn’t be a bit surprised” seems by far the more apt name.

Take the bar at the Algonquin Hotel, New York, where in the 1920s a gang of wits and wise-asses including Harpo Marx, playwright George S Kaufman and author Edna Ferber used to congregate, presided over by Dorothy Parker. They were known collectively as the Algonquin Round Table in society gossip columns, but referred to themselves as the Vicious Circle, which, given that Parker’s soundbites include (of Katherine Hepburn’s acting) “She runs the gamut of emotions from A to B” and “If all the girls who attended the Yale prom were laid end to end, I wouldn’t be a bit surprised” seems by far the more apt name.

Dorothy Parker even laid into her own Vicious Circle in later life, saying of it: “These were no giants… Just a bunch of loudmouths showing off, saving their gags for days, waiting for a chance to spring them…”

The real ‘giants’ that Parker had in mind where the likes of Ernest Hemingway and F Scott Fitzgerald, two literary luminaries themselves not averse to propping up the odd bar: both used to hang out and get disgracefully drunk at the Ritz bar in Paris. Hemingway was also a familiar face at Harry’s New York Bar: the most famous watering-hole in the French capital and possibly in the world, with a quite spectacularly glamorous history of celebrity clientele (from the days when ‘celebrity’ still meant something, rather than being a catch-all term for anyone who’s been in Hollyoaks). Coco Chanel, Rita Hayworth, Humphrey Bogart and even the Duke of Windsor used to drop in, perhaps to sip a Bloody Mary – the classic hangover ‘cure’ supposedly having been invented at Harry’s.

Britain’s most significant literary pub circle is somewhat less glamorous than those Parisian salons and, one presumes, rather less vicious than Dorothy Parker’s nest of New York vipers. In the 1930s and 40s, The Eagle and Child in Oxford was the favourite haunt of donnish fantasy-mongers JRR Tolkein and CS Lewis, who would meet with their fellow ‘Inklings’ in the Rabbit Room, no doubt to puff on revolting tobacco pipes, imbibe ale from beloved tankards and chuckle ‘My dear fellow’ a lot. In a defection as controversial as Fernando Torres’ recent move from Liverpool to Chelsea, the Inklings eventually migrated across the road to the Lamb and Flag, but both pubs remain lovely places to down a pint to this day.

Other drinking dens with rich literary histories include Dublin’s Davy Byrnes pub, frequented by Joyce and Beckett; and the colonial Long Bar at Raffles Hotel, Singapore, graced by A-list authors including Joseph Conrad, Rudyard Kipling, W Somerset Maugham and Anthony Burgess.

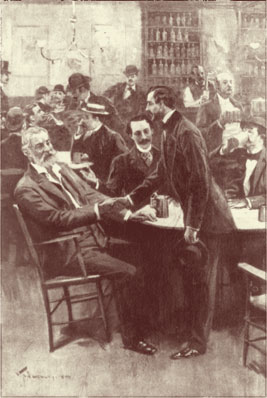

But there is one largely forgotten writers’ bar which deserves mention. I speak of Pfaff’s Beer Cellar, home to the original ‘bohemian’ movement in 1860s New York. The regulars included Fitz Hugh Ludlow, author of the The Hasheesh Eater and Henry Clapp, the newspaper editor who published Mark Twain’s first short story. Pfaff’s drinker George Arnold, a poet, even wrote an ode to beer called, appropriately enough, Beer (Why should I weep, wail, or sigh? What if luck has passed me by?

.. Have I not still /My fill of right good cheer,— Cigars and beer?).

But if Arnold was the Frasier Crane of Pfaff’s Beer Cellar, then its star regular – its Norm, if you like – was Walt Whitman, the poet and sage whose Leaves of Grass can lay claim to being the most influential work in American literature. (He also rather hypocritically wrote various pro-temperance essays; but then his most famous quote is “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself. I am large, I contain multitides…”)

I like to imagine Walt appearing at the top of the steps of Pfaffs, exactly like Norm at the door of the Cheers bar only with more beard, ready with a one-liner. “Have you had a beer yet, Walt?” “Sure have, Sam, I contain multitudes…but there’s always room for one more…”