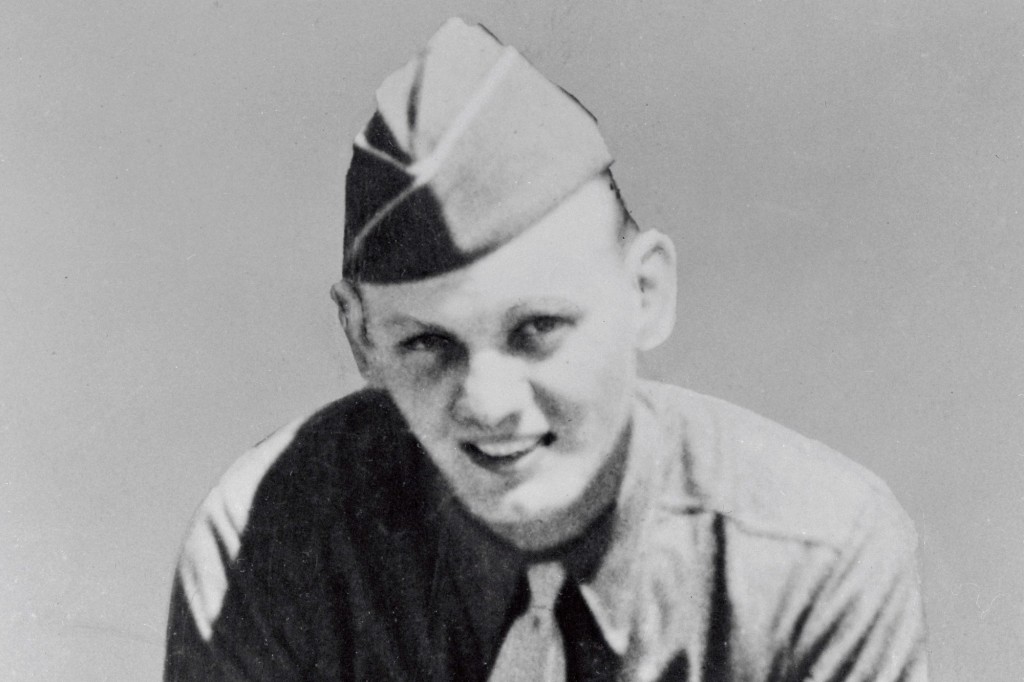

Edward Donald “Eddie” Slovik (February 18, 1920 – January 31, 1945) was a United States Army soldier duringWorld War II and the only American soldier to be court-martialled and executed for desertion since the American Civil War.

Although over 21,000 American soldiers were given varying sentences for desertion during World War II, including 49 death sentences, Slovik’s was the only death sentence that was actually carried out.

Slovik was born to a Polish-American family in Detroit, Michigan. As a minor, he was arrested frequently. In October 1937, he was sent to prison but was paroled in September 1938. After stealing and crashing a car with two friends while drunk, he was sent back to prison in January 1939.

In April 1942, Slovik was paroled once more. His criminal record made him classified as unfit for duty in the U.S. military, but in 1944 he was eventually reclassified as fit for duty and subsequently drafted by the Army. In August, he was dispatched to join the fighting in France.

While en route to his assigned unit, Slovik and a friend he met during basic training, Private John Tankey, took cover during an artillery attack and became separated from their replacement detachment. This was the point at which Slovik later stated he found he “wasn’t cut out for combat.” The next morning, they found a Canadian military police unit and remained with them for the next six weeks. Tankey wrote to their regiment to explain their absence before he and Slovik reported to their unit for duty on October 7, 1944. The US Army’s rapid advance through France had caused many replacement soldiers to have trouble finding their assigned units, and so no charges were filed against Slovik or Tankey.

The following day on October 8, Slovik informed his company commander, Captain Ralph Grotte, that he was “too scared” to serve in a front-line rifle company and asked to be reassigned to a rear area unit. He told Grotte that he would run away if he were assigned to a rifle unit, and asked his captain if that would constitute desertion. Grotte confirmed that it would. He refused Slovik’s request for reassignment and sent him to a rifle platoon.

The next day, October 9, Slovik deserted from his infantry unit. His friend, John Tankey, caught up with him and attempted to persuade him to stay, but Slovik’s only comment was that his “mind was made up”. Slovik walked several miles to the rear and approached an enlisted cook at a headquarters detachment, presenting him with a note which stated:

I, Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik, 36896415, confess to the desertion of the United States Army. At the time of my desertion we were in Albuff [Elbeuf] in France. I came to Albuff as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my fox hole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed over night at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American M.R. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND I’LL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THERE.

—Signed Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik A.S.N. 36896415

The cook summoned his company commander and an MP, who read the note and urged Slovik to destroy it before he was taken into custody, which Slovik refused. He was brought before Lieutenant Colonel Ross Henbest, who again offered him the opportunity to tear up the note, return to his unit, and face no further charges. After Slovik again refused, Henbest ordered Slovik to write another note on the back of the first one stating that he fully understood the legal consequences of deliberately incriminating himself with the note and that it would be used as evidence against him in a court martial.

Slovik was taken into custody and confined to the division stockade. The divisional judge advocate, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Sommer, again offered Slovik an opportunity to rejoin his unit and have the charges against him suspended. He offered to transfer Slovik to a different infantry regiment where no one would know of his past and he could start with a “clean slate”. Slovik, convinced that he would face only jail time, which he had experienced and found preferable to combat, declined these offers, saying, “I’ve made up my mind. I’ll take my court martial.”

Slovik was charged with desertion to avoid hazardous duty and tried by court martial on 11 November 1944. At the end of the day, the nine officers of the court found Slovik guilty and sentenced him to death. The sentence was reviewed and approved by the division commander, Major General Norman Cota. General Cota’s stated attitude was “Given the situation as I knew it in November, 1944, I thought it was my duty to this country to approve that sentence. If I hadn’t approved it–if I had let Slovik accomplish his purpose–I don’t know how I could have gone up to the line and looked a good soldier in the face.”

On 9 December, Slovik wrote a letter to the Supreme Allied commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, pleading for clemency. However, desertion had become a systemic problem in France, and the surprise German offensive through the Ardennes began on 16 December with severe U.S. casualties, pocketing several battalions and straining the morale of the infantry to the greatest extent yet seen during the war.

Eisenhower confirmed the execution order on 23 December, noting that it was necessary to discourage further desertions. The sentence came as a shock to Slovik, who had expected a dishonorable discharge and a jail term (the latter of which he assumed would be commuted once the war was over), the same punishment he had seen meted out to other deserters from the division while he was confined to the stockade.

The execution by firing squad was carried out at 10:04 a.m. on 31 January 1945, near the village of Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines. The unrepentant Slovik said to the soldiers whose duty it was to prepare him for the firing squad before they led him to the place of execution, “They’re not shooting me for deserting the United States Army, thousands of guys have done that. They just need to make an example out of somebody and I’m it because I’m an ex-con. I used to steal things when I was a kid, and that’s what they are shooting me for. They’re shooting me for the bread and chewing gum I stole when I was 12 years old.”

Slovik, wearing a uniform stripped of all insignia with a GI blanket across his shoulders against the cold, was led into the courtyard of a house chosen for the execution because it had a high masonry wall. Just before a soldier placed a black hood over his head, the attending chaplain said to Slovik, “Eddie, when you get up there, say a little prayer for me.” Slovik answered, “Okay, Father. I’ll pray that you don’t follow me too soon.” Those were his last words.

Twelve picked soldiers were detailed for the firing squad from the 109th Regiment. The weapons used were standard issue M-1 rifles with just one bullet for each rifle. One rifle was loaded with a blank. On the command of “Fire”, Slovik was hit by eleven bullets, at least four of them being fatal. The wounds ranged from high in the neck region out to the left shoulder, over the left chest, and under the heart. One bullet was in the left upper arm. An Army physician quickly determined Slovik had not been immediately killed. Just as the firing squad’s rifles were being reloaded in preparation for another volley, but before the reloading of the rifles was complete, Private Slovik died. He was 24 years of age.

Slovik was buried in Plot “E” of Oise-Aisne American Cemetery and Memorial in Fère-en-Tardenois, alongside 95 American soldiers executed for rape and/or murder. Their grave markers are hidden from view by shrubbery and bear sequential numbers instead of names, making it impossible to identify them individually without knowing the key. Antoinette Slovik unsuccessfully petitioned the Army for her husband’s remains and his pension until her death in 1979. Slovik’s case was taken up in 1981 by former Macomb County Commissioner Bernard V. Calka, a Polish-American World War II veteran, who continued to petition the Army to return Slovik’s remains to the United States. In 1987, he succeeded in convincing President Ronald Reagan to order their return. Calka raised $8,000 to pay for the exhumation of Slovik’s remains from Row 3, Grave 65 of Plot “E” and their transfer to Detroit’s Woodmere Cemetery, where Slovik was reburied next to his wife.

Although Antoinette Slovik and others petitioned seven U.S. presidents for a pardon, none was granted.

The US Army stockades of WW II were run to ensure that prisoners would not find them preferable to combat duty. In many cases, soldiers convicted of misconduct in the face of the enemy (or robbery, etc.) were put through some weeks of brutal drilling and sent back to the front. Slovik, according to Rick Atkinson, who gives him a page or two in The Guns at Last Light told those who questioned him that if sent back to the front he would desert again. Undoubtedly the Army thought it well to encourage the others.