Seamus Sweeney reads God’s Fifth Column: A Biography of the Age 1890-1940 – an unusual work by an author who at one time looked like becoming one of the greats…

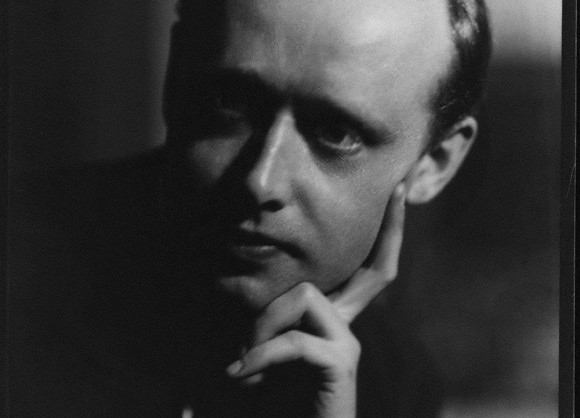

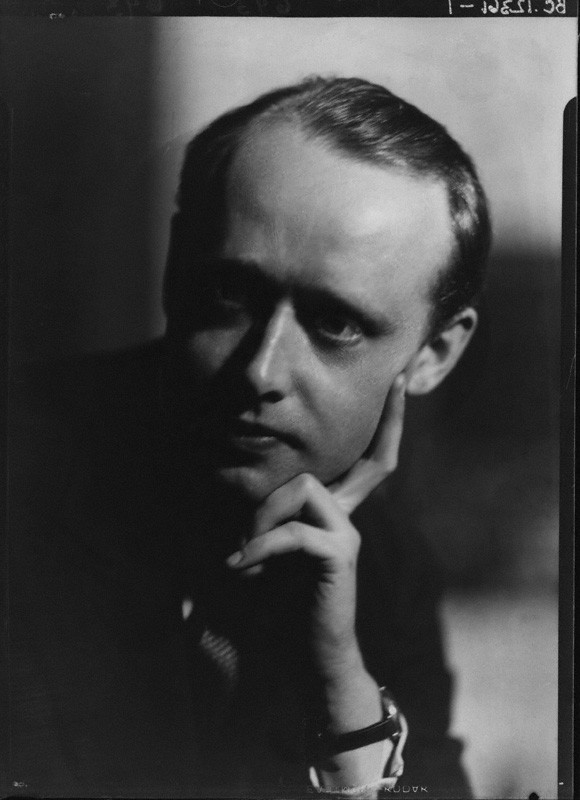

William Gerhardie has achieved an odd kind of fame; famous for not being famous.

He is a writer whose champions specifically focus on his obscurity, or rather the obscurity of his later life. Gerhardie was well-known in his early career, and the same few quotes that recur in his blurbs give testament to his appeal to his contemporaries. Evelyn Waugh said of him, “I have talent, but he has genius”, and for Graham Greene “to those of my generation he was the most important new novelist to appear in our young life. We were proud of his early and immediate success, like men who have spotted the right horse.”

Born in St Petersburg, Gerhardie was an English merchant of great wealth who was thrown into a sack in the 1905 Revolution. According to his son, he was only spared by being confused by the mob with Keir Hardie (this does have the air of a somewhat convenient anecdote). A Russian education for William was followed by being packed off to England to prepare for a commercial career of some kind; he ended up returning to the land of his birth as part of the failed Allied intervention after the 1917 Revolution.

As well as the acclaim of Greene, Waugh, Katharine Mansfield and Edith Wharton, Gerhardie also achieved a fair measure of worldly success, being taken up by Lord Beaverbrook as a potential protégé on the strength of The Polyglots. Beaverbrook’s attempts to turn him into a bestseller failed, and a lengthy decline into obscurity began. In 1931, aged 36, he published an autobiography, and moved into Rossetti House in London, behind Broadcasting House. He would remain there until his death in 1977, “a hermit in the West End of London” in the words of Holroyd and Robert Skidelsky’s introduction to God’s Fifth Column.

Every so often, Gerhardie achieves some revival degree of revivial. I myself tried to stoke the embers in 2006. William Boyd, a longtime admirer partly based Logan Mountstuart in Any Human Heart on Gerhardie. Michael Holroyd seems the most devout keeper of the flame.

There was another flurry of interest when his biographer, Dido Davies, died in 2013. Davies was a former heroin addict and author of sex manuals who had her funeral written up in Mary Beard’s blog.

Of his novels, Futility, Doom and The Polyglots are widely available. Futility is the most amenable to (my) contemporary taste, while Doom and The Polyglots are much shaggier stories but with much to recommend them. The latter, with its vain narrator, is notable for a remarkably clear-eyed portrayal of children free of sentimentality or faux-toughness. The former features a fictionalised Beaverbrook and a piecemeal apocalypse.

One of his works I have yet to track down is Meet Yourself As You Really Are written with Prince Rupert Lowenstein, father of the Prince Rupert Lowenstein (or more properly, Rupert Louis Ferdinand Frederick Constantine Lofredo Leopold Herbert Maximilian Hubert John Henry zu Löwenstein-Wertheim-Freudenberg, Count of Loewenstein-Scharffenec) who became financial manager of the Rolling Stones. In his biography A Prince Among Stones (which Sir Michael Philip Jagger, perhaps actuated by jealousy due to relative lack of names, responded: “Call me old-fashioned, but I don’t think your ex-bank manager should be discussing your financial dealings and personal information in public”) the younger Lowenstein describes the work:

He [Prince Rupert] was a writer, or more precisely, he had had a modestly successful book first published by Faber and Faber … which he had written with William Gerhardi, a novelist, playwright and critic, born in St Petersburg to English parents, who was a renowned and pioneering supporter of Chekhov’s writing in the West. (Gerhardi was also a keen supporter or the Tsarina, whom he had met as a young man, and believed that the best influence in Russia was, contrary to all normal belief, that of Rasputin who had been violently against the war in Germany…)

Meet Yourself as You Really Are was a very early example of home psychoanalysis, one of those psychological quizzes that offers instant insights into your personality and psyche … You are asked a long list of questions about all aspects of your life, covering everything from childhood to phobia, social behaviour to daily routine. I remember one that asked ‘Do you like your bath water tepid/hot/very hot?’ … From these answers and a scoring systems, you could discover your personality type among multiple permutations (three million possibilities, the book’s strapline proclaimed) leading to a number of basic key type.

William Gerhardi and my father had decided to name these different types after rivers, so you might at the end of the process discover you were the Rhine, the Nile, the Tiber or the River Thames, the latter with its conclusion ‘You’re the sort of poor mutt who always pays.’

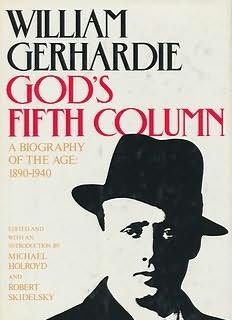

After his death, within various cardboard boxes labelled “DO NOT CRUSH”, was found the manuscript posthumously published as God’s Fifth Column. He had been working on this from 1939, and it made it into the Metheun catalogue of upcoming publications for Autumn 1942, but was then withdrawn (the relevant correspondence disappeared during the War; Gerhardie claimed he had withdrawn it at his own request for revision).

The “god’s fifth column” of the title is the comic spirit, subverting humanity’s well-intentioned, seemingly rational plans. Gerhardie defines it thus:

God’s Fifth Column is that destroying agent – more often the unconscious agent, sometimes malevolent or maladroit in intention – of spirit within the gate of matter. Its purpose is to sabotage such structures and formations of human society, built as it were of individual human bricks, as have proved to be unserviceable for association into larger groups of suffering units because insufficiently baked by suffering to cement with their immediate neighbours.

Later, he writes “Comedy is God’s Fifth Column sabotaging the earnest in the cause of the serious.”

Despising overarching explanations of history, and keen to defend the individual against all the collectives, from family to state, that seek to the control the “suffering unit” that is the individual person, Gerhadie’s history is a series of tableaux, of scenes in which the same figures -Tolstoy, Shaw, Margot Asquith, Arthur Balfour, various royals of various nations – recur.

Holroyd and Skidelsky edited out a quarter of the text which was unready for publication; the bulk of the text relates to the 1890-1919 period, with the next twenty years much more briefly dealt with. Gerhardie’s judgments are direct, his authorial voice magisterially certain of his subjects. A sample:

Bernard Shaw sent the greater writer of the Russian soil [Tolstoy] his The Shewing Up of Blanco Posnet, which drew a blank from Tolstoy, who answered that he ‘looked forward to reading it with interest’. Which, in author’s vocabulary, may be taken to mean he had already dipped into the thing without much interest and elected to write before he had to confess disappointment. In his accompanying letter Shaw stressed that virtue was ineffective because habitually cloaked in pious language, and would gain by the prestige of blunt, full-blooded, pithy speech, in which vice masquerades attractively before an admiring adolescent world.

This suggestion also seems to have drawn a blank. Virtue knocked dumb by meekness drew tears from Tolstoy’s old eyes, and he could not see it swaggering in jackboots.

But the letter is key to Shaw. He is a swaggerer, and he knows it and enjoys it. A man of trepidation in most things, he takes a double step. Metaphorically, even physically, as he strides up like a conquerer before the cine-camera. He adds an incongruous flourish of defiance to his old-maid’s signature: uses belligerent barrack room terms to convey Salvation Army sentiments.

This extract is fairly representative. God’s Fifth Column is full of entertaining anecdote, and Gerhardie has extracted from a host of memoirs of the age a host of arresting observations and unexpected encounters. His style, lapidary in Futility, tends to the verbose (not to mention tendentious) here, and ironically given his disdain for the great abstractions that press on the “suffering unit”, much of the narration is taken up with abstraction.

Read at length, the style becomes slightly grating; however as a book to dip and out of, it works very well.

God’s Fifth Column is available to buy online for 1p. If you would like to recommend one of the countless books that can be bought for a penny (or a cent) email us at editorial@thedabbler.co.uk

I actually have Meet Yourself As You Really Are! Well, either have or had – I think it’s still lurking somewhere. A fascinating book, more philosophical than psychoanalytic. My father had a copy when I was a boy (and I went through the questionnaires in quest of my Real Self). Years later I found a hardback copy in a charity shop (and my then teenage daughter also tackled the questionnaires). I believe a review of Futility (by me) was posted on The Dabbler a while ago…?

Indeed there was, Nige, and here it is.