Tens of millions of Britons learnt to read with the Peter and Jane books. In her second piece for The Dabbler, Ladybird expert Helen Day examines how the books – and their revisions – reflected British middle-class life, or an ideal of it…

Do the words ‘Peter and Jane’ take you back to a warm, fuzzy, nostalgic place in your memories? The rose-tinted hues of distant childhood? Or do they remind you of the horrors of primary school, of being tortured into reading by the terrible two (and Pat the dog).

Apparently over 80 million of us have learnt to read with Ladybird’s Peter and Jane books . And some of the books are still in print; I still see them for sale in my local bookshop.

Based on Head Teacher William Murray’s system of teaching reading, the Key Words scheme is founded on a recognition that just 12 words make up one quarter of all the English words we read and write and that 100 words make up a half of those we use in a normal day. Teach children these key words first, and they are well on the way to making some sense of most texts. So, step by step, page by page, these words are introduced and repeated (one might say hammered) to reinforce them as the length and difficulty of the texts increase.

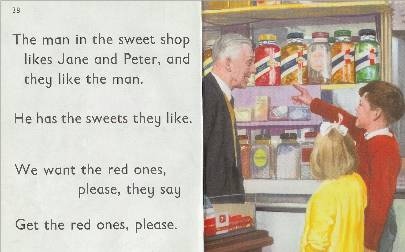

This is reassuring and confidence building for the young reader – but doesn’t make for punchy prose or dynamic dialogue. Here’s an example of chit chat in the P & J household:

A nostalgic idyll

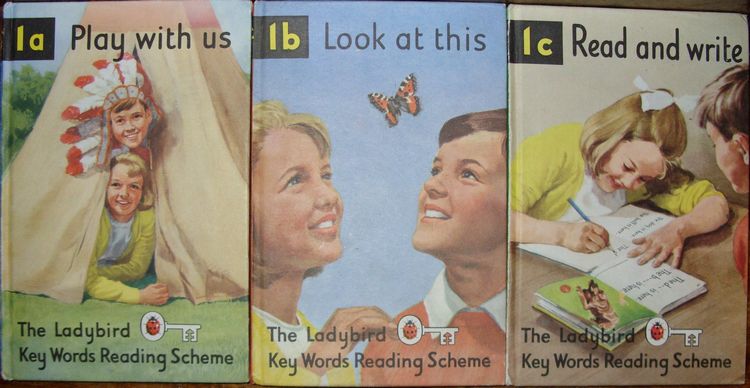

The first books were issued in 1964. Ladybird employed a number of different artists to bring to life Murray’s text: Harry Wingfield, Martin Aitchison, Frank Hampson, Robert Ayton and John Berry. These artists all had very different painting styles (Aitchison and Frank Hampson had previously worked on the classic comics The Eagle and The Marvel) but the brief was to produce appealing, naturalistic artwork and obviously the main characters, Peter and Jane, had to be recognisable throughout.

The first models for Peter and Jane were two local children who lived near Wingfield in Sutton Coldfield and who were only 4 or 5 years old at the time. Subsequent artists used their own models, adapting the pictures for the sake of consistency. This is why Peter and Jane in the 1960s books seem to have only one main outfit each – a white frock and yellow cardie for Jane and shorts and red jumper for Peter.

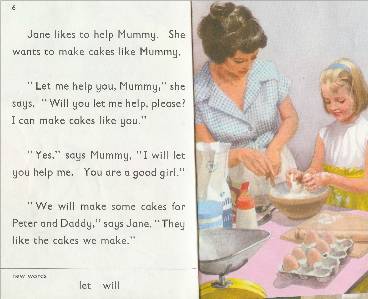

It is said of Peter and Jane that they are very ‘English middle-class’. The fact is that the childhood depiction of these children would have had much more in common with a privately educated middle-class child in Edinburgh than with a working class English child in Bradford or Portsmouth. The ‘culture’ represented is not Scottish, Welsh or English – but some 1950s concept of what was considered ‘proper’.

But then of course it’s easy to measure the Peter and Jane books with a contemporary yardstick (a metre stick?) and to forget their real context. To repeat an excellent observation made by journalist Cressida Connoly, in their time Peter and Jane were actually …

…an antidote to the privileged country children of popular literature, such as Swallows and Amazons or the Famous Five. Ladybird children didn’t go to boarding school; they went to the local newsagent’s on their bicycles. The childhood of Ladybirds was egalitarian and unsnobbish, depicting suburbia as the kind of utopia that town planners always intended it to be.

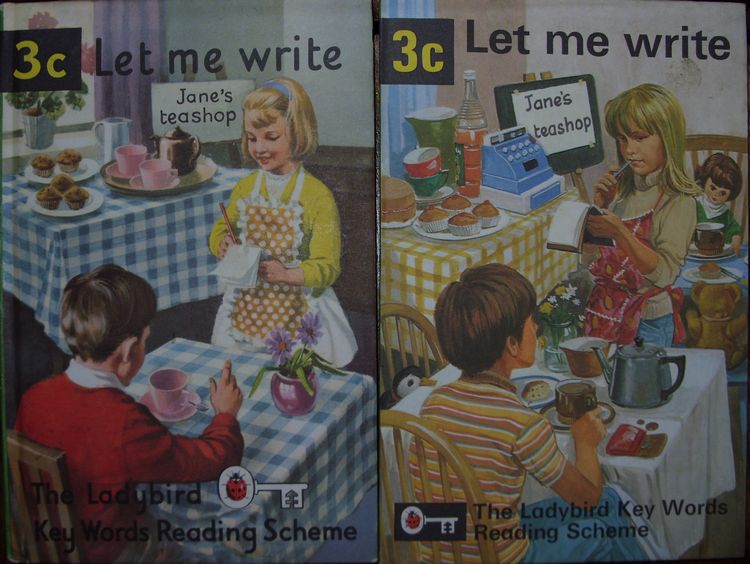

That’s the 1960s version of Peter and Jane. However, in 1970, only 6 years after first publication, Ladybird decided that the books needed some updating.

Goodbye sweetshop

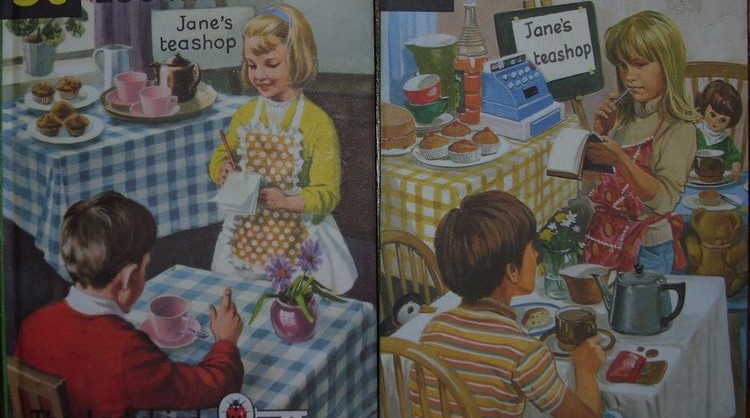

The first thing you notice is that in the 1970s version Jane now gets to wear jeans and is seen playing with roller-skates where once she played with dolls. The scenes portrayed look less ordered and serene. Play time is messier and the children appear to bicker more.

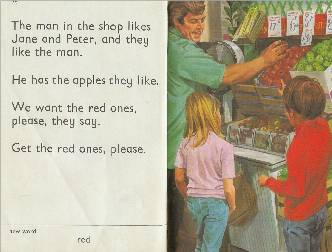

Perhaps the biggest changes in the first few books are all to do with sweet consumption. Whereas the Peter and Jane of the 1960s would visit the sweet shop…

…the 1970s Peter and Jane go to buy apples instead.

(This change was considered so important that even Murray’s text – so carefully worded and so rarely tampered with – was adapted in the revised books.)

I wonder if the original target audience were aware of the nostalgic, retrospective feel to the Peter and Jane books when they first came out? This, I think, is one of the most interesting aspects of this series, because you can immediately see the point. The softly luminous, idealised pictures of Peter and Jane’s home life and activities have their roots firmly in the 1950s and before.

Perhaps there was an awareness even then that these idyllic domestic tableaux were unreal and presented a world that had never existed. Or is it that those years, between the mid-sixties and early seventies saw exceptionally dramatic social change for families?

If you flip through the pages of a 1970s revised edition, it will still feel pretty modern today (which the first version absolutely does not). Of course there are no mobile phones, designer trainers or computer games – but the children have scruffy hair, wear jeans and T-shirts and don’t tidy up after themselves.

Averting the Ladybird gaze

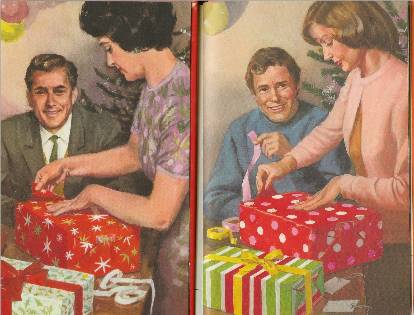

It is hard to imagine the Mummy and Daddy of the mid-60s artwork even being on speaking terms with their 70s equivalents. 1970s Daddy was expected to play more of a role in Peter and Jane’s affairs, whereas in the 1960s version he might watch with detached indulgence the scenes involving Mummy and the children. Here you can see the old Daddy looking on and the new Daddy helping out. Don’t strain yourself Daddy!

In fact, the Peter and Jane books are almost the last time that Ladybird dealt with the cosy nuclear family.

From the late 1960s onwards the new books that were published no longer focus on family life. Either non-fiction or fairy-tales or tales of animals (Hannibal the Hamster) or fruit and veg! (The Garden Gang) or science fiction.

Even the next reading schemes avoid looking too closely at the family – Puddle Lane is vaguely set in fantasy distant past, late-Victorian England with Gruffles and Griffles. The children involved are always playing out on the street. The adults are neighbours or The Magician. The cats – Tim and Tessa – seem to be raised by a single-mother and even the parents of the mice are absent for most of the series. The Sandlewood Girl and Iron Boy are parentless and are sort-of adopted at the end.

It’s as if, from the 1970s the cosy Peter and Jane family was no longer felt to be relevant, comfortable territory. But this was Ladybird – safe, national treasure – who could hardly bring out their own Ladybird version of “Jenny lives with Eric and Martin”.

So instead they averted their Ladybird eyes and focused elsewhere.

Years ago, I was asked by a newspaper to pick a book that changed my life. I chose ‘Look at this’.

I remember being very cross with my parents when they bought it, telling them that I didn’t need to learn to read. I clearly thought that it was too high a mountain to climb – I was four years old. But the genius of the ‘Key Words’ system made it a doddle.

It seems absurd that Peter and Jane was abandoned for being dated, as children accept characters on their own terms. I didn’t read Enid Blyton wondering why I didn’t have a nanny or go to boarding school. It’s very gratifying to see that the books are now getting the recognition they deserved.

Great article. I’d love to know where I can read more.