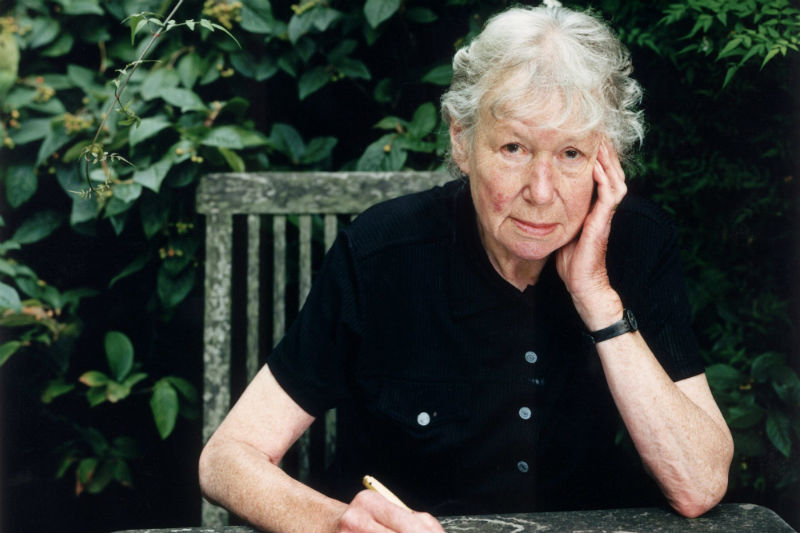

Dabbler editor Brit has written a piece about The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald here – and in a fine example of great dabbleminds thinking alike, later recalled that we’d featured the book on this site back in 2010. Here’s ZMKC’s 1p book review…

The Bookshop, by Penelope Fitzgerald (available at 1p here) concerns the attempt by a widow called Florence Green – “small, wispy and wiry, somewhat insignificant from the front view, and totally so from the back ” – to set up a bookshop in Hardborough, a small town on the East Anglian coast. Too late, Florence discovers that, in opening her establishment, she is going against the wishes of Mrs Violet Gamart, “the natural patroness of all public activities in Hardborough”. As Mrs Gamart tells Florence, when she invites the widow to a party, she has long been planning to use Florence’s premises as an arts centre.

“Chamber music in summer – we can’t leave it all to Aldeburgh – lecturers in winter … do, won’t you think it over?” Mrs Gamart says. In reply to Florence’s protests – “We have lectures already …The Vicar’s series on Picturesque Suffolk … comes round again every three years” – Mrs Gamart explains that the town needs “to be a good deal more ambitious”, withdrawing from Florence then, “with encouraging nods and gestures, into her protective horde of guests.”

Within the framework of this seemingly insignificant story, against the backdrop of Hardborough’s unequal battle with vile weather – “The beginning of November was one of the very few times of the year when there was no wind” – and the encroaching sea, Fitzgerald, who explained in an essay in 1989 that she was “drawn to people who seem to have been born defeated or, even, profoundly lost”, portrays in miniature the eternal struggle between the weak – those who, like Florence, have “a kind heart, though that is not of much use when it comes to the matter of self-preservation” – and the ruthless, who, like Mrs Gamart, do not hesitate to use their “cousin’s second husband, who was something to do with the Arts Council and …[their] cousin once removed, who was soon going to be high up in the Directorate of Planning and …[their] brilliant nephew who sat for the Longwash Division of West Suffolk and had already made his name as the persevering secretary of the Society for Providing Public Access to Places of Interest and Beauty, and … Lord Gosfield who had ventured over from his stagnant castle in the Fens,” in order to ride roughshod over those who get in their way.

Despite a brief flicker of hope when a higher power, in the form of Mr Brundish – “It was well known that Mrs Gamart, as patroness of all that was of value in Hardborough, would have liked to count him as a friend, but since she had been at The Stead for only fifteen years and was not of Suffolk origin, her wishes had been in vain. Perhaps her presence had not been drawn to Mr Brundish’s attention” – seems to be on the point of exercising its benign influence, the end is never really in doubt for Florence. It doesn’t matter. The book is not a novel of suspense; it is, to use AS Byatt’s characterisation of Fitzgerald’s writing, a “funny and terrible” account of the cruelty and vanity of human relations.

And it is largely its funniness that makes the book so enjoyable. Just as the air in Hardborough is shot through with damp, so Fitzgerald’s sense of the absurd saturates the text. Its other great virtue –and this is true of all Fitzgerald’s novels – is the terse clarity of the writing. Fitzgerald’s ability to conjure vivid scenes and characters in only half a dozen sentences astonishes me over and over again. In 10 lines, she skewers Mrs Gamart, her husband, their relationship and their setting:

“Silver photograph frames on the piano and on small tables permitted a glimpse of the network of family relations which gave Violet Gamart an access to power far beyond Hardborough itself. Her husband, the General, was opening drawers and cupboards with the object of not finding anything, to give him an excuse to wander from room to room. In the 1950s there were many plays on the London stage where the characters made frequent entrances and exits out of various doors and were seen again in the second act, three hours later. The General would have fitted well into such a play. He hovered, alert and experimentally smiling, among the refreshments, hoping that he would soon be needed, even if only for a few moments, since opening champagne is not woman’s work.”

She manages Milo North, who does something in TV, in a dozen words: “Milo North was tall, and went through life with singularly little effort.”

The book is very short, which I regard as a virtue. Ever self-critical, Fitzgerald admitted in an article in 1993 that she would have liked to make it still shorter, by removing the wonderful opening paragraph in which Florence sees:

“a heron flying across the estuary and trying, while it was on the wing, to swallow an eel it had caught. The eel, in turn, was struggling to escape from the gullet of the heron and appeared a quarter, a half, or occasionally three quarters of the way out. The indecision expressed by both creatures was pitiable. They had taken on too much.”

Making that cut would have been a mistake, but the fact she was thinking about it reveals the rigour with which Fitzgerald approached her writing. There are plenty of authors who might take note of her self-discipline. In The Bookshop there is not a wasted word.