If you thought The Hellfire Duke was something else, wait until you meet his uncle Goodwin – as we continue our weekly serialisation of Jonathan Law’s The Whartons of Winchendon…

Rismin! Accoron! Osmindor! Rumbonium!

High summer in deepest Bucks – and something very strange is stirring in the woods. The woman stalks slowly around the pit, calling on the demons by name, commanding them back to hell. The two men follow suit, perhaps a trifle awkwardly: Osmindor! Rismin! At times, the woman addresses a certain George, although this doesn’t seem to be the name of either man; otherwise the talk runs on treasure, the Duke of Lorraine and his servants, a certain Queen Penelope LaGard. Accoron! Rumbonium!

We are deep in the Chiltern woods, although it doesn’t look much like the high forest – all soaring uncut beeches – that brings the ramblers and the picnickers today; in 1684 the woods are denser, scrubbier, more entangling. Not the kind of place that anyone would walk for fun. In the last years of Charles II this is wild country; the haunt of footpads, semi-feral charcoal burners, outlaws and outcasts of every stripe. A sink of superstition and – in persecuting times – a refuge for every type of dissent. Even so, it’s hard to know what to make of the three characters chanting over the pit. The lady is in her fifties and rather stout (could she be pregnant?); decently dressed, but you know somehow that life has been a struggle. Her companions look like gentlemen, of sorts; one sixty-odd, stocky, with an almost comical air of shrewdness about him; the other much younger, slight, perhaps a bit fey. A Whig insider would doubtless have the older man pegged as John Wildman, veteran MP and a former postmaster-general. He might even know that the other fellow was briefly in Parliament too – what d’you call him, younger brother of Tom Wharton, family owns a deal of land in these parts: said to be a bit of a mooncalf.

Yes, it really is time we caught up with Goodwin Wharton.

***

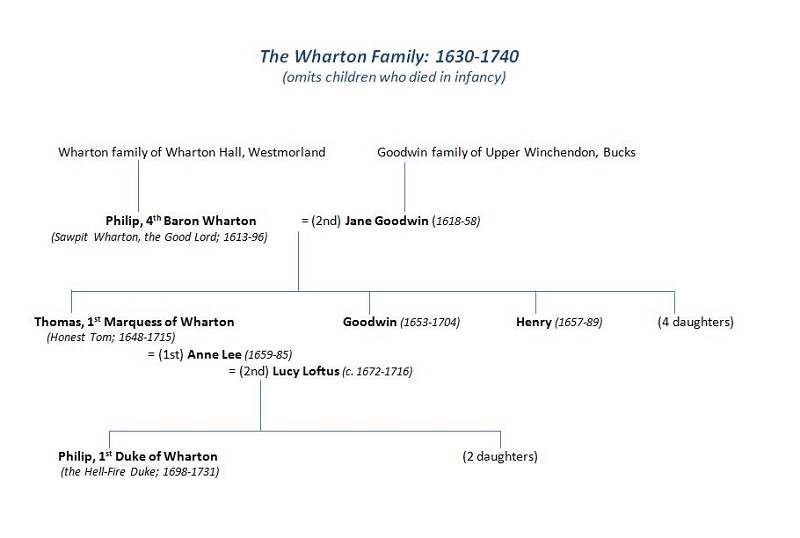

We left Goodwin – the second son of Philip, the ‘Good Lord’ – at a decidedly low point. His botched affair with Anne, the young wife of his brother Tom, was just the latest in a series of ventures that left him looking pretty foolish. He was also more or less broke. To an extent, Goodwin’s problem was the classic one of the younger son; he had no estates or income of his own and no trade or profession. This made him dependent on the goodwill of Lord Wharton, a prickly man who made no attempt to hide his low opinion of Goodwin and his preference for the extrovert Tom. Being an enterprising sort, Goodwin had struck out on his own as an ‘inventor-projector’, obtaining a patent in 1675 for his “new inventions for buoying up ships sunk in the sea” and another for “an ingenious design … for the squenching of public fires”. He had also developed equipment for deep-sea diving and tried it out himself in a quest for sunken treasure off the Isle of Mull. When all these enterprises failed, Goodwin attempted to follow Tom into politics, getting himself elected to Parliament in 1680. In his maiden speech he had stunned his listeners with an extraordinary attack on James, Duke of York – the soon-to-be James II – denouncing him as a coward and a traitor and accusing him (inter alia) of starting the Great Fire of London. Goodwin was horrified to find that he had alienated not just the Court party but also the Whigs, who regarded his speech as wholly counterproductive and possibly insane. His parliamentary career seemed over before it had begun. To cap it all, there was now this affair with Anne, which had ruined things with Tom; by 1682 Goodwin had come to regard himself as “generally hated and slighted by my own relations” – an outcast from the Wharton world of wealth and power.

Perhaps as compensation, Goodwin had become increasingly preoccupied with alchemy and the pursuit of occult knowledge. Unfortunately, his first attempts in this line had proved calamitous; he had put his trust in an alchemist named Broune, who had fleeced him unmercifully before vanishing. However, thanks to an extraordinary meeting in the spring of 1683, Goodwin knew that his luck was at last on the turn. From now on everything was going to be different.

***

It was in one of the poorest quarters of London that Goodwin came upon Mary Parish, a lady who has been described not absurdly as “one of the most imaginative and versatile women that England has ever produced”. Now in her early fifties, Mary was a healer and wise woman who made a precarious living through the sale of love charms and herbal remedies. Although she had clearly seen better days – and perhaps took a little too much brandy – the story she now told Goodwin was an amazing one that opened a new world of possibilities in his mind.

Mary had been born at Turville, a small village high in the Chiltern woods. Some years before her birth, the family had come into sudden money from an unknown source, thus arousing much local gossip. She would learn the truth of the matter when she was six or seven years old. Her grandfather now confided a great secret: that he had found a crock of fairy gold while digging a charcoal pit in the woods at Northend – and that an inscription on the pot promised a good deal more to those who knew where to look. Mary took to haunting the Northend woods and on one occasion saw the fairies dancing in the glade. Recognizing her special talents, Mary’s family sent her to learn medicine with a wealthy uncle, who also introduced her to alchemy and the occult arts. However, an unwise marriage and a deal of bad luck led to Mary being thrown into Newgate for debt. Here she made friends with a condemned felon named George, who agreed to become her attendant spirit after his death – a capacity in which he would serve her faithfully and well. There followed two more disastrous marriages, leaving her with a total of 20 children, all of whom died in the Great Plague (Mary would remain both astonishingly fertile and remarkably careless of her offspring).

Although her healing gifts had brought her some years of prosperity, Mary was now undeniably poor – a circumstance that she blamed largely on the jealousy of Sir Thomas Williams, the royal physician. However, she had recently discovered something that promised a revolution in her fortunes. While walking on Hounslow Heath, she had heard church bells ringing beneath the earth and the sound had carried her into the Lowlands – the marvellous underground kingdom of the fairies. Here she had visited the royal palace – a dwelling of unimaginable splendour – and became friendly with the King and Queen, who had shown her extraordinary signs of favour. With a bit of luck – and perhaps a bit of help – riches beyond the dreams of man would soon be hers to command. As a religious man, Goodwin could only see his meeting with Mary Parish as providential. With her secret knowledge and his education, social connections, and (occasional) access to funds, what might they not achieve? Within days, Goodwin had moved Mary into better lodgings, not far from his own. A partnership was formed that would last to the end of their lives.

***

For the rest of 1683 Mary would hold Goodwin in thrall with her detailed, almost anthropological accounts of the Lowlanders and their curious life under Hounslow Heath (the entrance to the fairy world must have been somewhere under Heathrow Terminal 4, which could explain a good deal). Born three hundred years later, Mary could surely have made it huge as a writer of fantasy fiction. By her account, the fairies were mortal but extremely long lived, often retaining their youthful appearance for over a thousand years. Although they looked about three feet tall, they were in fact a normal human size and chose to diminish themselves by wearing special demagnifying breastplates (clearly, she had Goodwin sussed as a gadgets man). The fairies’ ability to appear and disappear at will was likewise achieved by advanced technological means. Over the weeks to come Goodwin would acquire an expert knowledge of their social arrangements, customs, and religion (Roman Catholic, but involving a strict adherence to the Jewish Law). He would also become familiar with the leading figures of the Lowland world and their personal and dynastic rivalries; with King Byron, Queen Penelope LaGard, and Princess Ursula LaPerle, the Queen’s beautiful but treacherous sister; with Cottrell, an evil confessor to the Queen, and Father Friar, an aged counsellor who was also a great alchemist; with the Duke and Duchess of Brittany, the Duke of Lorraine, and the decidedly dodgy fairy Duke of Hungary.

Having heard all about these very interesting people, and their still more interesting gold, Goodwin could hardly wait to get networking; it was not long before an opportunity arose. That April Mary’s spirit guide, George, brought a message from the Queen of Fairies saying that she would be only too happy to visit Goodwin in his rooms. Disappointingly, she twice failed to keep the tryst and on a third occasion found Goodwin asleep and lacked the heart to wake him. To make up for this, Queen Penelope promised to receive both Mary and Goodwin in her palace on May Day – but was forced to cancel when her period came on unexpectedly (the fairies took a strict Mosaic line on these things, making it impossible for her to see any man at such times). This excuse would be repeated so often over the months and years that even Goodwin’s innate patience and chivalry would begin to wear thin.

Although summons to the fairy palace would arrive quite regularly, actually gaining admittance proved strangely difficult. On one occasion Mary and Goodwin would make it as far as the gates of the Lowlands, only to find that the entrance area was flooded. On another they travelled to Hounslow but were met by the news – as always, relayed to Mary via the faithful George – that King Byron had drunk too much and was in no state to receive them. They would soon hear that the King’s excesses had in fact caused his death – and that any visit would have to be put off until after the long mourning period decreed by fairy custom.

This was all hugely frustrating for Goodwin, but in the midst of this new debacle he began to glimpse a momentous possibility. Although the Queen proved no better at keeping appointments, her recent messages carried hints that were too strong to ignore; it appeared that she would now like to marry Goodwin and make him the King of Fairyland. In fact, she found him so irresistible that for some weeks she had secretly been having sex with him while he slept – sometimes as often as three times a night. This, Goodwin realized, would explain his tiredness and his otherwise puzzling backache. Autumn brought sad news that the Queen had suffered a dangerous miscarriage, losing twin boys that had clearly been fathered by Goodwin. Penelope’s health was badly affected and for all her great love she would not be able to come to Goodwin for many months.

By a curious synchronicity, these events had a parallel in the human world. That summer Goodwin and Mary had sealed their partnership by becoming lovers, despite the 20-year difference in age. The morning after they made love for the first time, Mary announced that she had conceived a boy (a fact soon confirmed by George). Two nights later, the couple again had sex and Goodwin was surprised to learn that she had once more conceived. If his disappointments had ever tempted him to give up on Mary – and at times, in his weaker moments, they had – Goodwin now saw that the two of them were bound together by more than a lust for gold. In due course Mary was delivered of twin boys; one died soon after birth but the other – a fine lad named Peregrine – was handed over to a nurse for safekeeping. Although Goodwin would never actually get to see the boy, this was not for want of fatherly concern – he would pay uncomplainingly for Peregrine’s care for the rest of his life. As with the Queen, firm appointments would be broken off at short notice for the most annoying of reasons, including illness, repeated minor injuries, and lack of clean clothes. Within a few days of the birth Mary declared that she was pregnant with another four children.

The spring of 1684 brought further journeys to Hounslow but no greater success in gaining an audience. Eventually, there came an exciting promise that the Queen would come for Goodwin in a fairy coach and whisk him off to the Lowland colony at Moorfields, where the fairy Pope would perform the marriage. However, this plan was stymied by a freak accident on the road and the untimely start of the Queen’s period. As the summer dragged on, the marriage of Goodwin Wharton and Penelope, Queen of the Fairies would be postponed for one extraordinary reason after another – the most alarming being an attempt by the fairy Duke of Hungary to poison her with a dish of chocolate. Frustrating as all this must have been, the summer brought one major triumph for Goodwin; belatedly seeing the dangers of delay, the Queen made a public announcement confirming that Goodwin was the new King of Fairyland, and that Peregrine would be his successor.

***

Given the endless difficulties that seemed to accompany all dealings with Queen Penelope and the Lowlanders, Mary and Goodwin had wisely begun to concentrate on a more mundane scheme – that of recovering the rest of the fairy gold buried in the woods at Northend. By the end of 1683 they had already made two exploratory journeys into the Chilterns and had located the site of the treasure, which turned out to be extensive. Unfortunately, the gold was protected by an evil spirit named Rumbonium, who was not at all disposed to be helpful. Hope, however, was offered by another spirit called Bromka, who let them know that Rumbonium was always absent on Monday afternoons, leaving the coast clear.

Here was promising news, certainly, but the treasure hunters had a problem in that they were now almost destitute of funds. As well as extracting a few guineas from his father, Goodwin had the inspired idea of bringing in an old acquaintance as financial backer – the former postmaster-general, John Wildman. A veteran plotter against both Charles I and Cromwell, Wildman had made a fortune from the estates of exiled royalists and was as well known for his shrewd business sense as for his tortuous conspiracies. In 1684 he was just out of the Tower for his alleged role in the Rye House Plot to murder Charles II and his brother James. Wildman fell in eagerly, if warily, with Goodwin’s schemes and put up some 300 guineas for a piece of the action.

So it is that on a Monday in July, 1684 Wharton, Wildman, and Mary make their way through the woods to the remote hamlet of Northend (accompanied, of course, by the invaluable George). The partners are relieved to find Rumbonium absent – but shocked to learn that three even more troublesome spooks are now in possession: Rismin, Osmindor, and the terrible Accoron, who menaces Mary in the form of a dragon. This introduces a tedious delay; before they can do anything else, the partners will clearly have to exorcise these devils and cast them into hell. Hence another trudge to Northend, and hence the terrible rites of exorcism in the woods. The demons are sent packing, but it turns out that the treasure is too vast for the three partners to take away unaided. For the next visit, therefore, a crew of (invisible) fairy servants are hired from the Duke of Lorraine – 50 guineas paid up front by Wildman. The servants are ready and waiting when Bromka announces, without so much as an explanation, that the treasure has just, well, gone. As if it had never been. But not to despair: a much greater prize is buried nearby – the mysterious Urim and Thummim from the temple of Jerusalem, rescued during the sack of that city in AD 70 and strangely preserved in a Chiltern beech wood. This, Bromka explains, is now in the keeping of a deceased Jew named Ruben Pen Dennis, who will happily hand it over – if they will only come back in a week. And so here they are again, the three treasure seekers, pushing their way through thorns and thick woods to arrive at their rendezvous with Bromka. Who tells them, sorrowfully, that they are fifteen minutes too late: the sacred treasure of Jerusalem has also vanished – like fairy gold, like the dream of a summer night.

As it turned out, this was the last foray into the Northend woods. Although Mary and Goodwin were keen to try again, John Wildman seemed increasingly preoccupied. After the Whigs’ great enemy James II ascended to the throne in early 1685, Wildman became caught up in the complex web of plotting that led to the Monmouth Rebellion in June of that year. Indeed, it seems likely that Wildman had already earmarked his share of the treasure, should he ever get his hands on it, for the funding of that ill-fated venture (the divinatory powers of the Urim and Thummim would doubtless have come in handy too). With the collapse of Monmouth’s hopes at Sedgemoor, Wildman fled to the safety of the Continent, as old Lord Wharton would do just a few months later. By a curious irony, the Good Lord is said to have buried his own treasure – amounting to some £20,000 – in dense woodland only a few miles from the haunted ground of Turville and Northend.

The overlap of Monmouth’s rebellion with the Northend treasure scheme is worth a moment’s reflection. Until now, Goodwin’s dealings with fairies and spirits might have seemed merely eccentric – and in any case utterly removed from the political world of Lord Wharton and his favoured son, Tom. From this point forward the two spheres would increasingly converge. The strange world of Goodwin Wharton was about to get stranger.