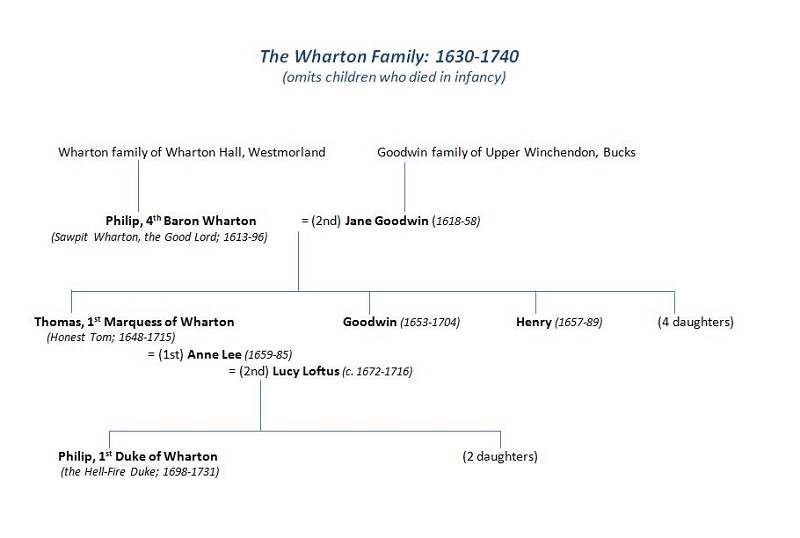

Continuing our weekly serialisation of Jonathan Law’s The Whartons of Winchendon, the story of Thomas Wharton takes a turn for the darker and stranger…

Although Tom Wharton spent his last years in the incongruous role of a much honoured elder statesman, he would be outlived by one last, semi-mysterious scandal – a story so strange that a chronicler hardly knows what to make of it.

Tom had married for a second time in the wake of the Revolution, his bride being the beautiful Lucy Loftus, a clever young thing who had come into huge estates in Ireland on the death of her father (at the Siege of Limerick: the ball that took his head off can still be seen in St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin). At the time of the marriage, Tom was 44, Lucy half his age. According to Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the couple were well matched indeed – Tom being “the most profligate, impious and shameless of men” and she in truth no better: “unfeeling and unprincipled; flattering and fawning, canting, affecting prudery and even sanctity, yet in reality as abandoned and unscrupulous as her husband himself.” Although it was said to be a love match, the marriage seems to have been an ‘open’ one almost from the start, with each partner turning a blind eye to the other’s amours and intrigues. The gossip ran that Tom was now so desperate for an heir that he didn’t much care who supplied it.

At some point early in the new century Tom enjoyed a brief flirtation with Dorothy (‘Dolly’) Walpole, the giddy young sister of Sir Robert Walpole, a rising star of the Whigs who would later emerge as Britain’s first ‘prime minister’. Far from discouraging the affair, Lady Wharton is said to have lured Dolly into their London home on some pretext, knowing that this could only end in one way; her motive was perhaps a spiteful desire to see the girl’s reputation ruined. Getting wind of what was afoot, Sir Robert apparently stormed down to the Wharton house and removed his sister by force. In a few years Dolly would be safely married off to Charles Townshend, a leading ally of Sir Robert and the famous ‘Turnip Townshend’ we all learned about when doing the Ag Rev at GCSE. At this point the story gets decidedly odd. It is said that when Townshend – who was known for his foul temper – learned of his wife’s association with the notorious Lord Wharton, he immediately tore her from their children and had her locked her into her rooms at Raynham Hall, Norfolk; there she remained, solitary and broken-hearted, until her death a decade or so later. Some versions of this strange, black tale have ‘Turnip’ informing the world at large that his wife was dead – and even holding a fake funeral in the family chapel. Others say that Townshend had her poisoned. Whatever the truth, Dolly would go on to enjoy a curious immortality as the ‘Brown Lady of Raynham Hall’, one of the best known and most photogenic of all English ghosts.

Although this story seems implausible on any number of counts – could the sister of a serving prime minister really be so easily disappeared? – something about it seems to require acknowledgment. At the very least, it testifies to the dark glamour of the Wharton name in the decades after Tom’s death. It also embodies the strange swerve into the Gothick that becomes such a feature of the mid-18th century – a swerve no less evident in the career of Tom Wharton’s son and heir, Philip, which we must now begin to consider. Indeed, the collapse of the Wharton family fortunes from this time forward is so spectacular as to have a touch of the uncanny about it – a suggestion of a curse or doom. It is as if poor Dolly Walpole had put a hex on the whole damned pack of them.

***

The longed-for heir had finally arrived at Christmas 1698 and rarely – even in that dynastic age – can a new-born have been loaded with such a weight of expectation. For Tom Wharton, there was never a doubt that his son would become a great man, a mighty champion of the good old (Whig, Protestant) cause for the new century. As a sign of his ideological inheritance, young Philip was given the name of his grandfather, the Good Lord Wharton. And as if to confirm his due place in the scheme of things, the child’s godparents were none other than King William III and Princess (later Queen) Anne. From his earliest years, young Philip was trained up to be an orator and a statesman, with his father taking personal control of his education and drilling him in politics, history, and rhetoric. Visitors to the house, including Joseph Addison, were treated to displays of Master Philip’s extraordinary wit and eloquence – and came away convinced they had witnessed a prodigy. Tom himself seems to have all but worshipped the boy, although there may have been a good deal of emotional neglect mixed in with all this burdensome attention.

The blow came just when the future of the Wharton family must have seemed most rosy – in the months after the accession of George I, with his known partiality for the Whigs and liking for ‘Honest Tom’ in particular. In the early weeks of 1715, Philip, still only 16 years old, eloped with one Martha Holmes, the daughter of a penniless Irish soldier. Tom at once flung himself into a fury of activity, pulling every string he knew in order to have the marriage annulled. When he learned that nothing could be done, the great Lord Wharton – who was already showing signs of strain from over-work – took to his bed and never got up again. Astonishingly, this man widely regarded as completely heartless seems to have died from some kind of broken heart. Reactions to the news proved as partisan as ever. For Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, there had never been any man “so constantly right in all things that concerned the true interests of England”. For the Tory diarist Thomas Hearne, the world could only be better without this “great, atheistical, knavish, republican, Whiggish, villain”.

Surmounted with a black funeral helm and crest, the coffin of Thomas Wharton was carried into the tiny church at Winchendon and interred by that of his first wife, the poet Anne. It was the day after Easter and for three minutes there was a total eclipse of the sun across southern England; birds went to roost, the stars were seen in the sky, and a cold dew fell on the horse gallops and sheep pastures of Winchendon.

***

Some five or ten years later the last resting place of the Lord Wharton would be imagined in quite different terms by Donato Creti, a Venetian painter who had been engaged to memorialize a set of English worthies for a rich Whig client. In Creti’s ‘Allegorical Tomb of Thomas Wharton’ the quiet earth of Winchendon has been supplanted by a dreamy Italian landscape out of Claude; the statesman’s elaborate pillared tomb is bathed in evening sunlight and guarded by vast umbrageous oaks – symbols of the English constitution that Tom had done so much to remodel (‘to save!’ bellow the Whigs; ‘to ruin!’ whisper the Jacobite Tories). In the foreground, various allegorical bods strike noble or didactic poses. It’s a bit hard to take seriously. Creti’s picture aims for the heroic-elegiac-sublime, but a modern viewer will mostly find it just odd – who are these people and why are they holding some kind of al fresco toga party in a National Trust garden? Even if you’re attuned to it, as few of us these days can be, the 18th-century grand style seems deeply inappropriate to the life of Honest Tom, rakehell and schemer. Where are the horses, the women, the rough and tumble of an 18th-century election campaign? You’d need a Hogarth, surely, to make something real out of all that.

But do look again. Like many such essays in the allegorical manner, Creti’s work becomes steadily more mysterious the more you try to decode it – and steadily more haunting. The winged lady on the pedestal is, I take it, Liberty – although she might just as well be Fame, or any one of a dozen other worthy things. The Minerva-like figure with the helmet and spear is probably Constancy – Tom showing a granite-like firmness in his political opinions if in nothing else; the lady to her left, with the sceptre and crown, would then be Good Government. Unless Minerva is in fact a bloke (that’s quite a masculine calf he/she is toting), in which case the couple have got to be King William and Queen Mary. The ladies with the harp and (?) tambourine are Muses, perhaps – reflecting Tom’s love and patronage of music. That is, if they aren’t the two Mrs Whartons: the poet Anne, the famously beautiful Lucy. Other figures, like the nearly-naked old gent in the left foreground, seem quite inscrutable. Now I think of it, he must be a river god, as he seems to be leaning on an oar, but I can’t speak for his relevance: an allusion perhaps to the Thames-side estate at Wooburn? (He seems too venerable for Tom’s own stream, the little Thame at Winchendon). And what are those slightly kitsch putti doing here? A hint at Tom’s many profane loves?

In all this solemn bustle it’s easy to miss the real drama, which is going on at the foot of the steps that lead to Wharton’s tomb. Here you’ll find the only figure in contemporary dress – a slightly epicene youth who I take to be Philip, the son and heir. The old man beside him gestures dramatically, striving to direct the boy’s attention to his father’s monument, to Liberty, to Fame, to whatever it is this allegory is trying to be about. Philip appears to have seen something quite different, stares off in the opposite direction. Perhaps he has seen a ghost. Whatever he is looking at, it isn’t in this picture.