A real treat this week as Mahlerman hails the ‘aural magic’ of Claude Debussy, the leading exponent of musical impressionism…

When Beethoven introduced his Third Symphony (Eroica) at the birth of the 19th Century, nothing like it had been heard before. The density of his ideas, the challenging way he develops them, and the demanding emotional content spread across a vast canvas puzzled the Viennese audiences. Today, two hundred years later, it is deemed by many to be the most influential work in all of music, marking the emergence of the Romantic epoch.

At the close of that same century in Paris Achille-Claude Debussy introduced a slight piece, starting with a languorous, sexy flute solo and lasting less than ten minutes. In Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, the composer was attempting to destroy the rhetoric of the classical era, and set the music of the 20th Century on its way. Musical impressionism had arrived, and with it the composer who was to become perhaps a greater revolutionary than even Beethoven, and certainly the greatest French composer who ever drew breath.

The sensuality and eroticism apparent in faune had first appeared a year earlier when the composer was just thirty-one. The String Quartet in G minor, opus 10, the composer’s sole essay in the quartet form is, along with the Ravel Quartet, one of the seminal impressionist works in the genre. The impressive-sounding title is, however, something of a pastiche. It is the only composition by Debussy that carries a key signature, and the opus number (10) in double figures, is solely there to convey a miasma of substance. The work is cast in a conventional four-movement form but manages, via shifting tempi and exotic harmonies to sound like nothing that had come before. The composer had spent some time in Russia at the pleasure of Tchaikovsky’s patron Nadezhda von Meck, and listening to the enchanting third movement Andantino, document expressif of this exquisite work, the influence of Borodin can be heard without undue strain, and the introduction of mutes gives a distant, introspective quality to the music. Aural magic.

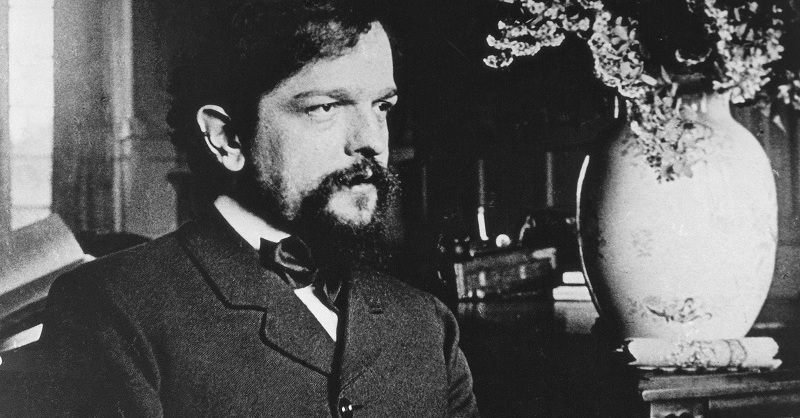

The physical appearance of a man and the way he comports himself is rarely a marker for the depth of his genius, and so it was with Debussy. A brachycephalic head sat atop a short, plump, pale body; his face and the top of his head were flat, and between high Mongolian cheek bones were bulging, heavily lidded eyes set below a capacious forehead. He was abnormally touchy, quick to take offence and sensitive to the point of mania. And yet – the pointed fawn-ears were perhaps the most sensitive ever gifted to a musician and, although he was no virtuoso pianist, his touch led many listeners to believe that the pianoforte had ceased being a percussion instrument. The composer Alfredo Casella remarked that

One had the impression that he was actually playing on the strings of the instrument, without the mechanical aid of keys and hammers….. the result was pure poetry.

By the turn of the century Debussy was composing piano music of increasing complexity and sophistication and in 1903 he published the extraordinary travelogue Estampes (Prints), cast in three movements. The first movement, Pagodes conjures-up Asia, and the composer’s fascination with the music of Javanese Gamelan. The third movement Jardins sous la pluie takes us back to France, quoting two children’s folk-songs. The central movement La soirée dans Grenade leads us across the Pyrenees into Spain – and no less an authority than Manuel de Falla stood in awe of Debussy’s ability in this movement, to offer an ‘impression’ of Iberia, without actually quoting folk material. Piano playing of uncanny authority, from the 28 year old Martha Argerich, recorded in 1969.

Have you heard of Debussy and of his nocturnes? After reproaching you in every way for having borrowed from the language of music to apply it to painting, now music comes in search of inspiration from your painting. What a turnaround! How things come full circle!

This short extract is from a letter dated June 1903 (probably the last he received) to the American painter James McNeill Whistler, from his close friend Theodore Duret, the French journalist and author. And yes, Debussy had seen the series of paintings (see below) given the collective name Nocturnes, and been inspired to write a series of his own – and in 1898-99 the three movement work for orchestra appeared.

This sort of music, seemingly vague, sensual, nebulous, is the sort of music we think of when we think of Debussy, and the Nocturnes are arguably his farthest-reaching forward leap into the future of music, and in the first movement Nuages (Clouds) we have the single most radical exploration of previously unknown tonality and timbre. Where Beethoven (in the Pastoral) described what he saw and heard – peasant’s merrymaking, bird-calls, a thunderstorm – we sense, we feel the slow movement of clouds across the sky, and what the composer expressed as ‘the immutable aspect of the sky and the slow, solemn motion of the clouds, fading away in grey tones lightly tinged with white’. He wasn’t dabbling; he knew what he wanted. See if you agree.

If it is indeed pointful to describe a thing by reference to its opposite, then mention of Beethoven again is germane. He was the living embodiment of the classical tradition that Debussy had little time for. The bar-line was part of Beethoven’s musical semantic language; Debussy often walked right through the bar-line, and never more so than in his only opera Pelléas et Mélisande, from a play by Maurice Maeterlinck. Started in 1893, no other work gave him so much trouble, and it was almost nine years later before the ink dried upon the last notes (Beethoven had a similar struggle with his only opera, Fidelio). After a shaky start, the opera is now, rightly, considered one of the supreme masterpieces of French art – but it is such a long, delicate, elusive piece, that an evening in the theatre can be, shall we say, taxing. Tempi are mostly slow, and if a producer is unable (or unwilling) to ‘produce’ the twilight, post Wagnerian atmosphere that this extraordinary score demands, the whole venture can fall apart quite quickly, as I have seen a couple of times. But in truth there is not a dull page in the work, and the truncated video we end with today is from the magical section at the start of Act 3 where Pelléas, barely able to contain his mounting sexual attraction for the waif-princess, is engulfed by the flowing tresses of Mélisande, this surely one of the most impassioned yet understated moments in all opera…..‘I can no longer see the sky through your hair’. Merveilleux!

fantastic MM, none more ethereal than Nuages, and your words as entertaining and educational as ever – when’s the book coming out? 😀

(+also I am liking the large format youtube videos)

I first heard the Nocturnes when I was 18 and remember being struck by how the music reminded me of the Whistler paintings. When I later learned that they were the inspiration for the music, my admiration for Debussy was even greater – his music didn’t just allude to Whistler’s Nocturnes. It was the Nocturnes.