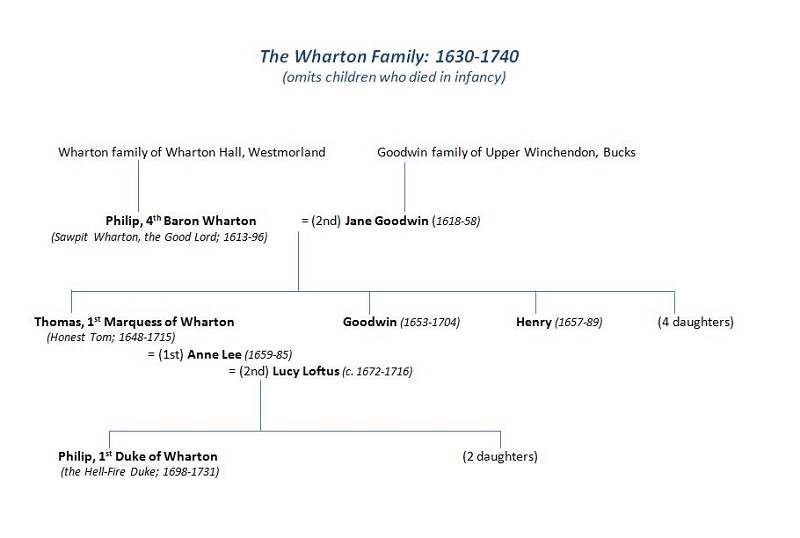

Continuing our weekly serialisation of Jonathan Law’s The Whartons of Winchendon (published for Kindle by Dabbler Editions and available to buy from Amazon now), we learn more about Thomas Wharton: powerful political fixer, habitual liar, saviour of the nation and pox-ridden traitor…

And so, rather implausibly, in the last weeks of 1688, Tom Wharton became a great man. As one of the makers of the ‘Glorious Revolution’, he was lionized by his own party, the now dominant Whigs, and would soon become one of its ruling cabal. From early 1689 he was both a member of the Privy Council and Comptroller of the Household – the official with the important role of liaising between the new King, William III, and the House of Commons. He would soon be acknowledged as one of the handful of men who effectively ran the country while William was away fighting his French wars.

As William no doubt knew, he owed as much as to Tom Wharton as to any man alive: quite apart from his role in the Revolution, it was Tom, in the Convention Parliament of 1688, who had moved that William be made King, rather than some sort of regent. And yet the relationship between the two men would never be easy. William respected Tom’s energy and ability, but is said to have mistrusted him, fearing that he was a Commonwealth man at heart (if Tom Wharton and friends could dispense so easily with one king, then why not another?). There was also a basic difference in outlook. At bottom, William was keen to conciliate all parties who accepted the Revolution settlement – not least because he had no wish to become a creature of the Whigs. By contrast Tom Wharton remained openly and relentlessly partisan, a man who made no secret of his desire to purge his enemies, the Tories, from every area of public life, by any means available. These were, after all, the men who had sent his friends and allies to the scaffold in 1682 and 1685; the blood of the ‘Whig Martyrs’ was crying for redress. But given his calculating nature Tom’s motives were probably as much strategic as personal; his overriding aim was to leverage the triumph of the Revolution into a lasting ascendancy for his own party. Every opportunity must be taken to brand the Tories as natural enemies of English liberty and the Protestant religion – men whose support for the Revolution could never be anything but self-serving and insincere. “If you intend to govern like an honest man, what occasion can you have for knaves to serve you?” he would rasp at William, in the rough manner the King would come to resent, and perhaps even fear.

This word ‘honest’ was never far from Tom’s lips and it is worth pausing to consider what he could have meant by it. In Tom Wharton’s eyes, to be ‘honest’ was above all to be a defender of “the honest old Whig interest” and an enemy to the forces of “Popery and slavery”, at home or abroad. Personal probity was something else altogether. So it was that T. Wharton acquired his ubiquitous nickname – one deployed with great bitterness by his enemies and with a more nuanced irony by his friends: Honest Tom. For by any normal standards Tom Wharton was not an honest man.

“Of all the liars of his time he was the most deliberate, the most inventive, and the most circumstantial” concluded the Whig historian Macaulay. Political contemporaries would marvel at Tom’s ability to tell any lie that would gain his immediate end – and to appear quite unabashed when found out a week, a day, or an hour later. More puzzlingly, he would often seem to lie for lying’s sake, when a plain truth could have served him just as well. Probably, the roots of this lay deep in his early experience. Tom’s relations with his domineering, Puritan father seem to have bred a habit of dissimulation, and this became more deeply engrained in the dangerous political atmosphere of the 1680s. Inveterate womanizing must also have played its part – as Tom’s great enemy Jonathan Swift was quick to suggest:

He seems to have transferred those talents of his youth for intriguing with women, into publick affairs. For, as some vain young fellows to make a gallantry appear of consequence, will choose to venture their necks by climbing up a wall or window at midnight to a common wench, where they might as freely have gone in at the door, and at noon day; so [Wharton], either to keep himself in practice, or advance the fame of his politicks, affects the most obscure, troublesome, and winding paths, even in the most common affairs …

As if to rub it in, Tom Wharton told his lies with a nonchalant air that let his enemies know just how much of a damn he didn’t give. Although the Tories found this insufferable – Lord Dartmouth complained of “the most provoking insolent manner of speaking that I ever observed in any man, without any regard to civility or truth” – they never seemed able to land one back. As Macaulay notes, “neither invective nor irony could move him to anything but an unforced smile and a good-humoured curse”. Tom seems to have possessed to a rare degree that most useful of all political gifts: a genuine and imperturbable shamelessness (think Thatcher, think Blair). “He will openly take away your employment today, because you are not of his party” seethed one opponent, and yet “tomorrow he will meet or send for you, as if nothing at all had passed, lay his hands with much friendliness on your shoulders …” Honest Tom Wharton was one of those politicians who inspire not just disagreement or dislike but a real, blazing hatred.

All this, it should be said, was accompanied by great gifts of organization and man management. By 1694 or 95 Tom was regarded as perhaps the greatest party manager the House of Commons had ever known. The general elections of the 1690s also revealed his extraordinary ability to get in the Whig vote, by fair means or foul. “Such a master of the whole art of electioneering England had never seen”, Macaulay would concede, “as a canvasser he was irresistible.” Tom Wharton never forgot a face, or a name, or a voter’s favourite tipple. And once he had inherited his father’s wealth and title – in 1696 – his pockets were very, very deep. From this date, if not before, he can be counted a full member of the so-called Whig junto – the “five tyrannizing lords” regarded by many as the true rulers of England at this time. Having got his hands on real power, Tom also had an idea of what to do with it, putting his considerable weight behind two epochal pieces of legislation: the 1701 Act of Settlement – the one that secured the Hanoverian succession – and the 1707 Act of Union with Scotland. In both cases the immediate motive was to block any future Jacobite restoration – and thus to create a world safe for Whig grandees; but in pushing these measures Tom Wharton, the fixer and tactician, can claim to have left a more lasting mark on English history than most.

***

Wharton’s rise to power suffered a serious check in 1702, with the death of William and the accession of Queen Anne, a staunch Tory of strong High Church views. Anne took grave exception to Tom’s morals and lack of religion (no doubt she remembered – as who could forget – the incident at Great Barrington and is said to have taken great pleasure in relieving him of his staff of office. Tom made the best of his new leisure by spending vast sums of money on Winchendon, his much loved country house in Bucks. The garden was remade in the Dutch style and graced with an enormous red-brick orangery – a declaration, no doubt, of Tom’s unchanging Revolution principles. A gardening project of another kind was initiated at Wooburn, the Thames-side estate he inherited from his father; in tribute to the pious old grump, Tom undertook to plant at least one specimen of every tree mentioned in the Bible. Other diversions were less innocent. Although Tom had remarried, mistresses came and went and no woman was thought to be quite safe in his presence. At the age of 60 he could still beat a man half his age in a duel – taking his old delight in disarming his opponent, forcing him to snivel for his life, and granting it with a shrug. He also rediscovered his passion for horse-racing, which often became the continuation of politics by other means; Tom would think nothing of transporting one of his prize mounts halfway across the country in order to deprive some Tory or High Church owner of a rich purse – which would then go straight into his election fund. By this time the ‘Wharton interest’ controlled some 25 parliamentary seats, including 10 in Bucks. In the general elections of 1705 and 1708 Tom threw himself into the campaign with his usual insane competitiveness, spending an estimated £80,000 of his own money on buying votes (in today’s terms, approaching £10 million).

Like her predecessors, Queen Anne would soon learn that you can’t keep an honest man down. The electoral successes of the Whigs brought the Junto lords back to power and Tom – newly created Earl of Wharton and Viscount Winchendon – was again a force to be reckoned with. Anne’s solution was to pack him off to Ireland, to serve as her Lord Lieutenant. The office brought near despotic powers and Tom deployed them in the usual enlightened style of the English in Ireland; the ferocious Penal Laws against Catholics were extended – although Tom appears to have been broad-minded enough to “whore with a papist” during his stay – and sales of employments and other kickbacks ensured that he left Dublin some £45,000 the richer (£5 million in today’s money). He also managed to incur the dangerous enmity of Jonathan Swift, whom he had unwisely passed over for preferment. In the 1710s Swift would keep up a relentless series of attacks on Wharton, who seems to have represented everything he most detested about a certain kind of Englishman and a certain kind of Whig. In his A Short Character of Thomas, Earl of Wharton and other writings Swift would eviscerate this “publick robber, adulterer, and defiler of altars” with a thoroughness bordering on the obsessive. Tom seems to have reacted with his usual sang-froid (in this respect, he must have been a satirist’s nightmare). Although Wharton was called back to England after only two years, a motion of impeachment was later quietly dropped: however gross, his peculations seem to have been within the understood limits of these things.

If the last years of Anne’s reign saw Tom at a low ebb – out of office and mauled by his opponents – apotheosis was only just around the corner. With the succession of the first George in 1714, Wharton’s hopes and plans and schemes of thirty years finally came to fruition; the future of limited Protestant monarchy seemed secured, the Tories were thrown into division and disarray, and the Whigs began almost half a century of uninterrupted power. As perhaps the chief architect of all this, Tom found himself smothered in honours; Lord Privy Seal; Marquess of Wharton and Marquess of Malmesbury; Marquess of Catherlough, Earl of Rathfarnham, and Baron Trim in the Peerage of Ireland. After a lifetime of noise and scandal, Tom was in danger of ending his days a revered elder statesman. To the younger members of his own party, in particular, ‘Honest Tom’ had become a legend; the “tutelary god whom our Whigs invoke and adore as the sole preserver of their country”, as the Duke of Portland put it. The Whig writer Abel Boyer agreed: for all the spite of the satirists, Lord Wharton had proved himself “the most active, most strenuous, and most indefatigable asserter of liberty; and the warmest and most inveterate enemy to popery and arbitrary power”.

To the Tories, however, Tom Wharton remained beyond the pale; Lord this or Marquess of that, he was still the man who once took a shit in a church (the story had grown: it was now Gloucester Cathedral, in broad daylight, on the high altar). In the Tory imagination, ‘Honest’ Tom would continue to loom large as an almost Satanic figure: not just another politician on the make, but a portent of godless power and lawless wealth – a truly dark lord. For Swift, Wharton remained quite simply ”the most universal villain I ever knew” and lesser writers followed in painting a picture of almost insane wickedness:

Industrious, unfatigued in Faction’s Cause,

Sworn Enemy to God, his Church and Laws,

He dotes on Mischief for dear Mischief’s sake,

Joins contradictions in his wondrous make …

Joins depth of Cunning with Excess of Rage,

Lewdness of Youth with Impotence of Age.

Descending, though of Race illustrious born,

To such vile actions as a slave would scorn …

His dignity and honour, he secures

By Oaths, Profaneness, Ribaldry and Whores;

Kisses the man, whom just before he bit,

Takes Lies for Jests, and Perjury for Wit,

To great and small alike extends his Frauds,

Plund’ring the Crown and bilking Rooks and Bawds;

His mind still working, mad, of Peace bereft,

And Malice eating what the P-x has left,

A monster, whom no Vice can bigger swell,

Abhor’d by Heaven and long since due to Hell.(Anon, 1712)

So: saviour of his nation or poxed-up maniac traitor from hell? On past form, it seems unlikely that Tom Wharton agonized much over the verdict of posterity. Having arranged the succession of the Crown, he was now concerned with his own dynastic issues: as much as old Lord Wharton, Tom was desperate for his son and heir to carry the great work forward (we’ll see how that turned out in the next two posts). Perhaps the last word should go to the age’s great arbiter of moral and philosophical questions, the 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury: Tom Wharton, he said, was the most mysterious human being that he had ever known.