The Whartons of Winchendon, is a new serialisation of Jonathan Law’s latest book, which is published for Kindle by Dabbler Editions and available to buy from Amazon now.

In this episode we meet Philip, 4th Baron Wharton, who was instrumental not only in the rise to power of his family, but also in the enshrinement of early English civil liberties. But as we will find in future episodes, his heirs would not prove so morally upstanding…

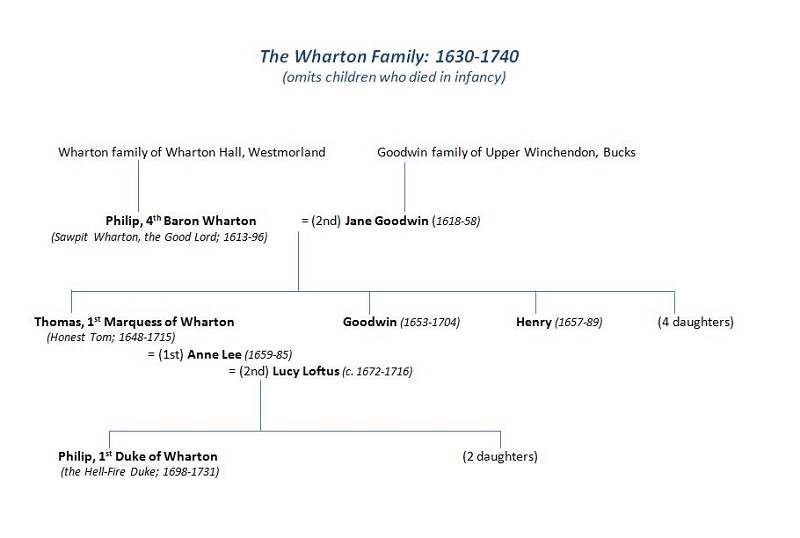

The story of the Wharton family and Upper Winchendon begins in 1637 – the last year of real peace before the Civil Wars. That September Philip, 4th Baron Wharton, married Jane Goodwin, heiress to large tracts of Bucks including the manors of Winchendon, Wooburn, and Waddesdon. When Jane’s father died in the Parliamentary cause, Philip – who already held extensive properties in the north – became one of the greatest landowners in the country. To enormous wealth he could add the advantages of stern good looks, a finely tuned political sense, and a reputation for piety that made him the idol of the Puritan clergy (who referred to him dotingly as “the Good Lord Wharton”).

With Parliament at length victorious, Wharton, a close friend and protégé of Cromwell, was widely seen as a man to watch. As Oliver knew well enough, the Good Lord had proved invaluable to the cause as a backroom fixer and committee man (as well, it seems, as a supplier of gunpowder). Of course, like any public figure, our man had his detractors, some of whom hinted that his contribution to the actual fighting had not been glorious: at Edgehill, his troops had been swept from the field by Prince Rupert’s cavalry and Wharton is said to have watched the rest of the battle from the refuge of a sawpit. True or not, the story inspired a nickname that would stick for the rest of his life: ‘Sawpit’ Wharton. Philip Wharton’s devotion to his political and religious views can hardly be questioned; but it was accompanied by an instinct for self-preservation that at times amounted to genius.

Something of this can be seen in his sudden decision, in late 1648, to abandon his London mansion and to settle at Winchendon. The timing can hardly have been an accident. Wharton’s move came only weeks after Pride’s Purge – effectively, the military coup that laid the foundations for Cromwell’s dictatorship. The reasoning that led ‘Sawpit’ to choose Winchendon, at that time one of his more obscure and modest properties, had everything to do with its location. His motives have been explicated most shrewdly by J. Kent Clark, the leading modern historian of the Wharton clan:

Lord Wharton wished to remain on the fringes of political action. At Winchendon … about forty-five miles from Westminster, he was within a very long day’s carriage ride from Whitehall, where in case of need he could use his personal friendship with the new governors to get favours for himself and his friends. In the normal course of things, on the other hand, he was far enough removed to keep the new regime at arm’s length and to parry, gracefully, Cromwell’s attempts to recruit him for service. Winchendon, in fact, may be seen as a symbol for Lord Wharton’s survival policy – later to be revived in the days of James II: In revolutionary times, one may be friendly with unpopular rulers and even accept favours from them. To serve them, however, and to earn those favours may prove dangerous or even fatal.

Wharton doubtless had real misgivings about the nature of the new regime; but his move also exhibits the deep, ingrained wariness that would enable him to outlive seven rulers of England. By choosing a life of rural retirement, he managed to avoid any part in the events leading to the death of King Charles, thus hedging his bets against a future restoration. In this way he was not only looking after his own skin but also safeguarding his long-term dynastic ambitions (an heir, Tom, had been born earlier that year). Cromwell’s blandishments, which would eventually include an offer of marriage between the two families, were firmly but courteously declined.

As his family grew around him – there would eventually be eight children – Lord Wharton sat tight at Winchendon and devoted his time to godly pursuits and his purse to beautifying his house and garden. Andrew Marvell was a guest, and some scholars think that his great but slippery poem The Garden was written here, among the fountains and implicated parterres; if so, it makes a nice fit with Wharton’s sphinx-like character and the various ambiguities of his situation. Although the Good Lord was a staunch Calvinist, a man known to take a stern view of play-going and Sunday travel, his friendship with Marvell shows that he was no puritan in the vulgar sense. A morbid self-denial would never be one of his vices. Our man took great enjoyment in music and poetry, and the collection of Van Dykes and Lelys he had built up over 20 years was said to rival that of King Charles himself. Indeed, Lord Wharton seems to have combined piety with wealth, and the power that comes from wealth, with an enviable ease. He was no doubt more honest than his enemies allowed. As an old man his proudest claim was that he had never taken a bribe, and in the strictest sense he may never have offered one. Yet when it came down to it, Lord Wharton – like any magnate of the day – was firmly of the school of C. Montgomery Burns: if extreme wealth doesn’t allow you to bend your fellow man to your will, then what on earth is it for?

With the death of Cromwell in 1658, Wharton decided to close things down at Winchendon and moved the household to Wooburn, his mansion at Bourne End – only twenty-odd miles to the south, but a world nearer the centres of power, where things were developing with alarming speed. In May 1660, when the second Charles landed at Greenwich, the 4th Baron was amongst the first to greet him. Although in mourning for his wife, Lord W. had carefully replaced the buttons on his black velvet costume with diamonds; very clearly, it would not do for anyone to mistake his feelings at this time. He would likewise take an ostentatious part in Charles’s coronation, spending something like a year’s income on trappings for his horses.

Considering his past, this was all most prudent. Where many of his old associates went to the gallows, or suffered fines and confiscations, Wharton remained free to enjoy his gardens and his music and his pictures. However, it would be unjust to see the Good Lord as some kind of Vicar of Bray. In his religious convictions, at least, he remained entirely consistent. During the long years of Anglican and Royalist reaction, he would prove a tireless patron of the nonconforming clergy, some 2,000 of whom were driven from their livings. In return, these men would provide him with a nationwide network of support, and sometimes of intelligence. For thirty years he would walk a dangerous tightrope, making Wooburn a hub of resistance to royal policy while evading any serious consequences for himself or his family. At times, his footing appeared to wobble. In 1663 Wharton was named in connection with the Farnley Wood plot, a conspiracy to murder Charles and re-establish the Commonwealth; he seems to have been perfectly innocent, but had friends who were not. In 1676 an imprudent word led to his summary imprisonment in the Tower, although he was soon freed on grounds of age and infirmity (he would live for another 20 years).

Given all this, it is no surprise that Lord Wharton supported the moves afoot at this time to enshrine Habeas Corpus in English statute law; a key step in the evolution of English liberties, yes – but also a matter in which he had some personal interest. Indeed, some accounts go further and hint that Wharton’s role in securing the passage of the 1679 Act was a mysteriously decisive one. According to these writers, the Act only managed to pass the Lords by a species of chicanery. Knowing that the vote was going to be very close, the teller for the ‘ayes’ took advantage of a moment’s inattention by his opposite number to count a particularly fat peer as five, thus carrying the Bill. You might think that this has every sign of being a tall tale, but the numbers are still there on the record – votes for 57; votes against 55; total number of peers in attendance 107. And, yes, some versions of the story have it that the teller for the ‘ayes’ on this occasion was none other than the Good Lord himself.

While old Lord Wharton was busy playing a wary and enigmatic role in the politics of the Restoration, the manor at Winchendon had remained empty and boarded up for some 15 years. However, the day came when his son and heir, young Tom, returned to the house on the hill, threw open the windows, and took up residence with his bride; it was 1673 and a new chapter in the history of this most remarkable family was about to begin.

fluid and easy style, and interesting subject matter = very enjoyable!