Ever tried to write a novel that wasn’t worthless? Douglas considers talent, mediocrity, the limits of creativity and the art of appreciation…

In A Mathematician’s Apology G.H. Hardy estimates that only five or ten people in a hundred can do something “rather well.” Considerably fewer are truly gifted. We do not each have a valuable talent waiting for discovery. We may dream of making names for ourselves, but most “talents” are talents only by inflation, and it may be that many true talents are never valued. The influence of the cult of achievement extends even beyond its membership. Those who renounce the pursuit of worldly accomplishment often do so with other more comfortably nebulous goals in mind: sainthood, perhaps, or self-realization. They’re chasing the same fox by another tail.

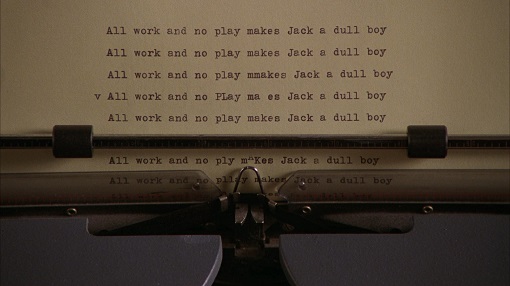

Hardy’s calculation is depressing. I suffered a fit of ambition myself in my mid-thirties. For more than five years I spent two nights each week working on a novel, and I took it through three drafts. Reading and re-reading it, writing and re-writing it, was a bruising, infuriating, ego-punishing business. What I ended with was perhaps better than some of what gets published today, but that’s saying awfully little when most of what gets published is an unjustifiable waste of both writer’s and reader’s time. Almost every book ever written more than deserves its inevitable oblivion.

My book surely will too, even if I were to find the will to push it through to a magical fourth draft. And then, even if I were to succeed in getting it published, I know well enough that it’s not something to be too ridiculously proud of. If working on it has taught me anything, it’s that I am no Herman Melville or Henry James. Tonic as it may be to fess up to that inadequacy, ambition rarely lets lack of genius to stand in its way.

It’s possible that I may have neglected avenues for achievement that were better fitted to me. Hardy writes that “poetry is more valuable than cricket, but Bradman would be a fool if he sacrificed his cricket in order to write second-rate minor poetry.” I know nothing about cricket or Bradman, but I’ll agree that you don’t give up on a first-rate talent merely because it happens to be for a second-rate activity. I manage to make a living in the business world without too much effort. What might I have achieved if I had focused my ambitions in that direction? Most days, however, it’s a struggle even to fake a tepid enthusiasm for work of the sort that actually pays the bills.

According to Hardy, first-rate minds care only for creation. If second-rate minds care for it too, so much the worse for them. They would do better, he says, to restrict themselves to the very second-rate tasks of criticism and appreciation.

Appreciation. The term, as he utters it, drips condescension. But I want to say that Hardy gets it wrong here. He shows that his scheme of values is off-kilter. It may be that I’m only plotting myself an escape from Hardy’s sentence, but I hate the idea that the worthiest of human endeavors is beyond the reach of most humans. Surely it’s not only scarce things that can have ultimate value?

Appreciation, in the sense of pure enjoyment, seems to me a better candidate than creative accomplishment for the title of “man’s true work.” It may sound Jeffersonian (“pursuit of happiness”), or Epicurean, or bourgeois of me to say so. I don’t mean that people with leisure are morally superior to those without it. But though it’s not an idea that lends itself to proof by argument, I do believe that, other things being equal, there’s no nobler human aspiration than simply to enjoy and delight in things. To appreciate a particular face, a meal, a tree, a note, a book, a fact, an idea is something available to most of us. To enjoy something to the limit of one’s capacity may be better than to create it.

This sounds like the argument in The Book of the Courtier, in which the courtiers argue in favor of well-rounded appreciation of many things rather than pedantic concentration on any one. Yet a couple of distinguished writers are represented as having participated in the discussions. In general, if one does as well as one can that which one does best, the world can’t ask more, and oneself probably shouldn’t.

On the other hand, there is G.K. Chesterton’s dictum that “Anything worth doing is worth doing badly.” That covers, well enough, anything done purely for one’s own amusement.

“(a) well-rounded appreciation of many things rather than pedantic concentration on any one” – basically the Dabbler credo!!!

1. Obligatory Sturgeon Quote: 95% of everything is crap.

2. I am reminded of my constant irritation with the Big Bang Theory theme song: We built a wall (we built the pyramids), Until we meet ET, I don’t get any credit for the Pyramids or Shakespeare or the Mona Lisa, and neither do you.

The Chesterton quote is a comfort, isn’t it?

That last paragraph is pretty moving.

BTW I reckon Hardy was grinding his axe.