Rita discovers the story of a little Quaker town that became the capital city of the U.S. for just one day…

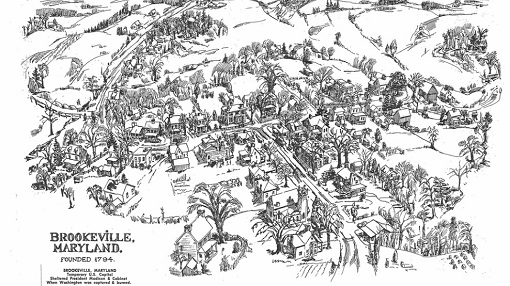

The charming little town of Brookeville is nestled in the suburban sprawl of Washington D.C. as it once nestled in the green and pleasant Maryland countryside. But suburban sprawl maintains a discreet distance, the better to sustain the illusion that here time stands still. Just a few minutes drive from my home in Gaithersburg, the epitome of unfettered suburban sprawl, I turn down a narrow country road that winds uphill and down dale through cornfields, woods, and farmhouses. Puffy white clouds float in a summer sky and if I blink it is just possible to ignore the asphalt and the road signs and imagine I am in a horse-drawn wagon instead of a car, traveling back to Brookeville’s one brush with history. Unlikely as it may seem standing amid the tiny cluster of eighteenth century buildings that comprise the old town, Brookeville was once the capital city of the United States of America. For just one day, and entirely due to the British.

The war of 1812 is but a footnote in American history, remembered now mainly for Francis Scott Key’s stirring poem The Star-Spangled Banner which became the National Anthem. So little Brookeville’s moment in the sun on Friday August 26th 1814 is but a footnote to a footnote. Two days earlier the British had overwhelmed American forces at the Battle of Bladensburg and surged unopposed into Washington D.C. burning the White House to the ground. By the time the British entered the capital 90% of the white population had fled, scattering to farms and villages in the Maryland and Virginia countryside. President Madison and his wife Dolley were among the last to leave. They traveled separately, she carrying the famous portrait of George Washington, ripped from its frame in her haste to get out of town. There followed the undignified spectacle of the President of the United States on the run for two days in the Virginia countryside as he tried to catch up with his wife. From the banks of the Potomac he watched Washington burn.

Meanwhile refugees from the burning city and soldiers on their way to Baltimore descended on the little Quaker town of Brookville in Maryland. The townspeople took them into their homes, setting up makeshift beds in parlors, and serving meals at all hours. As Quakers, Brookeville’s residents were opposed to war. Mrs. Bentley, wife of the Postmaster, explained: “it is against our principles to have anything to do with war, but we receive and relieve all who come to us.” Margaret Smith, wife of the president of the Bank of Washington, who brought all the bank’s coinage to Brookeville for safekeeping, wrote after her ten hour walk from the capital: “the appearance of this village is romantic and beautiful. Here all seems security and peace. The town is full of people and wagons. It now affords so hospitable a shelter to our poor citizens. I have never seen more benevolent people.”

Quakers were also abolitionists and the town was home to a number of free blacks at a time when half the population of Washington were slaves. The letters of the Washington refugees are full of euphemistic references to “the enemy at home” as much to be feared as the British. They were afraid the slaves would join the British forces and take up arms against their owners. Some sent their slaves to farms in the countryside to keep them isolated. Rumors of insurrection swirled and, Washington being perhaps as conspiracy minded as it is today, as they watched the city burn many believed the falsehood that slaves were responsible.

On Friday August 26th Brookeville residents were amazed by the unannounced arrival of President Madison accompanied by Attorney General Rush and a few other members of his cabinet. The President was guarded by a detachment of dragoons his party had met up with on the road. Knowing Dolley was safe with friends in Virginia, Madison was now intent on joining General Winder and his troops who had passed through Brookeville en route to Baltimore. The presidential party first stopped at the home of the town’s founder, Richard Thomas, but not realizing the President was in the group at his door, Thomas informed them he had no more room. So the honor of hosting the President fell to Caleb Bentley, a clockmaker, silversmith, and the town Postmaster. As word spread through the town the curious gathered outside the Bentley house hoping for a glimpse of their President. Madison was said to appear composed despite the national emergency and courteously greeted select visitors who were allowed into the parlor. The Federal Republican later reported: “At supper his excellency was quite talkative and cheerful for some minutes, but occasionally relapsed into silent gloom. He ate ravenously, and remarked that it was his first meal since breakfast, and he had rode 30 miles on horseback.”

So for less than twenty-four hours the Bentley house in Brookeville was the center of executive power in the United States. Madison spent his time issuing dispatches to his generals and writing letters, one to his wife Dolley, as well as getting some much needed sleep. On Saturday morning he received word that the British had left Washington in pursuit of the American troops on their retreat to Baltimore. The President decided to return to the capital city and regroup his scattered government. By noon he and his party were on the road and Brookeville’s brief appearance in the history books was over. Madison returned to a capital that, in the words of one observer, was “the most magnificent and melancholy ruin you ever beheld.” Later in the year, after the successful defense of Fort McHenry in Baltimore, the rather pointless war fizzled to an end with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent.

Today the Bentley house, renamed Madison House in honor of its illustrious guest, still stands on a dignified rise above Brookville’s main road. In 2012 the current owners won The Washington Post’s award for the best restoration of a historic home in Maryland, Virginia and D.C. Two of the surveying stones used by Richard Thomas to lay out the town in 1794 remain in the front yard, so despite the fact that he turned his President away at the door, the town’s founder steals a bit of his neighbor Caleb Bentley’s glory. President Madison actually did little more than pass through Brookeville, but traces of his visit can still surprise. While planting tulip bulbs in her garden the current owner of Madison House dug up the bowl of a clay pipe decorated with the Great Seal of the United States.

This story was immortalized in the film “Mr. Smith goes to Brookeville”. Not a huge box office success, as I recall.

The British did not pursue the Americans overland to Baltimore, but went back to their ships. They were landed to the east of the city and skirmished, but did not think it worthwhile to assault the field works the Americans had put up.

By the way, General Winder was not allowed to control the Maryland militia when he arrived in Baltimore: Samuel Smith, major general of that body and a U.S. Senator, managed the operations.

Maybe they pursued by water!

Run if by land, scoon if by sea?