Working at Waterstone’s in the early 1990s, Steerforth quickly discovered that bookshops were magnets for eccentrics, kleptomaniacs and the mentally ill – and that was just the staff…

Sometimes I find it hard to believe that I spent the best part of 18 years working in bookshops. Where did all the time go? It’s not even as if I wanted to be a bookseller. I just needed a job and my girlfriend told me that there was a vacancy in a new shop called Waterstone’s. I’d never heard of it.

I got the job after an interview with a woman with shaking hands, who already seemed tired and disillusioned with her new shop. That probably wasn’t a good sign. I was offered a starting salary of £7,250 p/a, rising to £7,500 if I completed my three month probationary period.

Even 20 years ago, if you earned less than £10,000 a year, your options in life were pretty limited. With such awful pay, the job could only be a useful stopgap. It certainly wasn’t a sensible career choice.

Sadly, I didn’t have a Plan B and my Damascene moment never came. Some booksellers passed through the shop like gap year backpackers in Goa, taking a breather before going on to enjoy successful careers in television or publishing. I stayed and became Colonel Kurtz.

I spent the early 1990s at Waterstone’s in Richmond – an affluent suburb of London that was quickly changing from old money into a ghetto for post-apartheid South African exiles, American business execs and semi-retired rock stars. I think my mother was the last working class person to grow up in Richmond. There should be some sort of plaque on her old house.

Starting at Waterstone’s was a baptism of fire. I wasn’t well-read in those days (I was more interested in music) and each shift was like being on Mastermind, except that the rounds lasted for three hours at a time and you weren’t allowed to make a mistake or say “Pass”.

Some people shouted at me because I hadn’t heard of the book they wanted. Others merely resorted to sarcasm or barely-concealed contempt. At first it was deeply humiliating, but as my knowledge and confidence grew, I realised that it was unreasonable for people to expect me to be omniscient. It wasn’t a personal failure if I’d never heard of an obscure, long out of print novel that was published in 1948.

I noticed that a lot of older people seemed to resent the young and welcomed the opportunity to bully them. Men in their 60s would regularly chastise our 18-year-old Saturday girl for her poor general knowledge of politicians of the 1950s, forgetting that they had lived four times as long, whilst middle-aged women expected me to be their gimp, running up and down the three flights of stairs until I’d reached the bottom of their long lists (sadly the demands stopped there).

The worst were the South African women, dripping in gold, with vulgar Gucci sunglasses and rottweiler accents: “Yeess, Ah’m wanting to know if you hev eeny books bah theess lady?” The answer was always Jackie Collins and even if the book was staring them in the face, it seemed to go against the grain for them to do anything for themselves.

Every day was a struggle, but luckily I picked the job up quite quickly and learned to talk with great authority on subjects that I knew nothing about. I also realised that I had a knack for making sure that we didn’t run out of the bestselling titles (harder than it sounds when publishers took up to three weeks to deliver and there were no computerised stock control systems).

But perhaps the most important lesson I learned was how to answer back in a way that wouldn’t get me the sack. Once people could no longer smell the fear, they treated me with respect and I began to enjoy my job more.

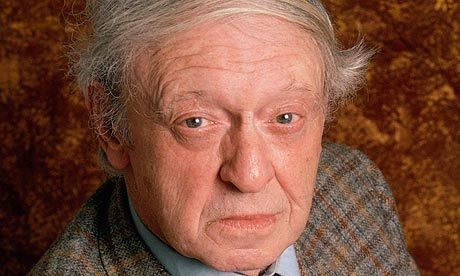

Interestingly, the really successful people – whether they were famous authors like Anthony Burgess or celebrities like Mick Jagger – were unfailingly polite. It was the noveau riche who were a pain in the arse. They were usually quite thick as well, but felt that their wealth conferred a natural superiority.

Anthony Burgess. One of my colleagues dared me to tell him how much I enjoyed his ‘Chocolate Orange’, but I chickened out.

For some reason that I couldn’t fathom, the most ghastly people always bought Ayn Rand or The Art of War, whilst the dippy ones couldn’t get enough of A Year in Provence. I tried hard not show my contempt for people’s book choices, but when one Tim-Nice-But-Dim customer held up a copy of The Bridges of Madison County and said “This is wonderful, isn’t it…” I cracked and launched into a Bernard Black-style diatribe.

Apparently the poor man left the shop looking as if he’d been horribly violated. I’m amazed he didn’t complain.

During my first year at Waterstone’s, I quickly discovered that bookshops were magnets for eccentrics, kleptomaniacs and the mentally ill – and that was just the staff (the most audacious book thief was a man called Desmond who decided that the most efficient way of stealing stock was to become a bookseller). We also had a loyal following of lost souls who spent so much time in the shop that their stock knowledge easily equalled ours.

In many ways bookselling left a lot to be desired. The money was terrible, working with the public was exhausting and the shift system meant that many evenings and weekends were wasted.

However, the best parts of the job more than compensated for the irritations. I loved having the freedom to spend vast sums of money buying new titles from publishers’ reps (all of whom seemed to be called Brian or Keith), taking a punt on an unknown author or range, only to find that I’d spotted a new trend, like the Aga saga craze. In my first year at Waterstone’s, two buying decisions alone paid for my salary.

I also loved meeting authors and publishers, deciphering the complex web of friendships and petty rivalries between people in the book world. I never read reviews in the same light once I realised how many of them were written by friends reviewing each others’ books.

Sometimes I even liked working with the public – usually on a quiet evening when there was time to talk to customers, find out what they liked and make recommendations. Seeing people enjoy the shop, relaxing in an armchair with a book from a new display I’d created was very rewarding.

The first year passed quickly. 12 months on I still had no idea what I wanted to do and although I hated being poor, I realised that I loved my job. The books were interesting, my colleagues were bright, funny people and I felt that I was quite good at what I did.

I stayed. The money gradually improved and by the time I was a manager in London, I was able to afford a mortgage, meals out and a decent holiday every year. It didn’t last. I ruined it all by having children and leaving London. I have lived in penury ever since.

I’d probably still be managing a bookshop now, if HMV hadn’t bought Ottakar’s. But I’m very glad I left. I don’t think that I could ever go back to working weekends, dealing with the public and putting up with head office edicts any more. Once you’ve tasted freedom, it’s hard to go back.

However I miss the fun: the buzz of a crowded shop on the last Saturday before Christmas, meeting old friends at drunken book launches and having a good bitch with the publishers’ sales reps. I don’t think there’s much fun in the book trade any more, so perhaps I was lucky to get out while I did.

You are obviously a true professional as evidenced by the fact that not once did you tell us you made your career choice because you really love books. I’ve been assured by at least two booksellers that is the very worst reason to get into the trade.

Never work in publishing if you love books.

I’m sure. Isn’t it funny how the rote assurance of the naive job applicant in so many fields is that they really love people, but in this field it’s how much they love books? Imgine applying for a job in a grocery store on the basis that one loved to eat, or selling cars on the basis that one loved to drive.

Also, people who love cooking shouldn’t become professional chefs, people who love writing shouldn’t become paid copywriters etc. Or as David Cohen so profoundly and succinctly put it: Don’t follow your passion.

Well, I wonder. I find it somewhat reassuring that Jamie Oliver is not gaunt, and found it troubling that one of the New York Times’s food writers had collarbones sharper than some of our knives. As for books, I think that the American chain Borders started to run into trouble when it was bought by Kmart. Certainly it helps to have business sense to keep your enthusiasms in check.

Working in high street shops is indeed an odd pastime, I’ve certainly met some strange folk in my time of standing behind a counter. I can well imagine that book shops attract all sorts of passing weirdos as you point out. Normally they always seem to be carrying random objects in a plastic carrier bag.

About thirty years ago a friend of mine worked in the Charing Cross Rd Waterstones with Ray Monk, the Wittgenstein biographer and scholar. He reckoned he became reasonably expert in Wittgenstein, his life and philosophy, by hanging round the bookstacks whilst Monk chatted with fellow scholars who’d dropped in for a chat. Monk’s reputation was such that they came from as far away as Australia. Don’t usually get that stacking shelves in a shop.

Love the Burgess portrait. Sad to see so few of his books on display nowadays. I think Earthly Powers should be on the A Level reading list.