Contrary to popular opinion, Frank Sinatra made some of his most interesting records well into his ‘September years’, argues Seamus Sweeney…

The conventional wisdom holds that Sinatra was, musically, most interesting in the mid-1950s; his collaborations with arranger Nelson Riddle and, to a slightly lesser extent, Billy May produced the classic albums which have become the key Sinatra repertoire. The conventional wisdom would have Sinatra, and the whole musical and cultural ethos he embodied, become suddenly irrelevant in the Sixties; I would like to write “some time between the Chatterley ban and the Beatles’ First LP” but it would plug straight into the lazy generalisations I am trying desperately to avoid.

In any case, the live 50th birthday album, “Sinatra At The Sands”, recorded in 1966 with Quincy Jones arranging and Count Basie and His Orchestra accompanying, is in this narrative the high water mark of Sinatra’s art. From then on, popular entertainment would never be the same again, as a million earnest documentaries urge us with a montage of Beatlemania, Vietnam protests, Woodstock and so forth.

Of course, the Sinatra songs that could be described as Karaoke Frank, the biggest hits which, rather unfortunately, define his art for all too many – “New York, New York”, “My Way” and “Strangers in the Night” (Sinatra would come to despise all three, and all are far more bombastic than the heights of his oeuvre) came from 1966 and after. Indeed, Sinatra released “Strangers in the Night” in April 1966. Yet conventional wisdom holds it that artistically, there was nothing really going on for Frank after two score and ten.

Sinatra’s September years actually present a fascinating, uneven, often thrilling soundscape. After 50, Sinatra’s music is often all too clearly casting around for a new identity, now that the pop cultural landscape has indeed changed. Sometimes, the results are indeed embarrassing: as well as a toe-curling version of Mrs Robinson, witness his version of Winchester Cathedral. But more often, we hear an artist searching for a new path, not only in art but in life. Many of the post 1966 albums feature variations on the theme of ageing.

These three albums are not necessarily the best of Sinatra after fifty, but three works which help to define his later career:

Francis A and Edward K (1968)

Francis A is of course Francis Albert Sinatra; Edward K is Edward Kennedy Ellington, AKA Duke. The arrangements are by Billy May, one of the stalwarts of Golden Age Sinatra. The album cover features childhood photos of the two main attractions, and the music therein has something of the warm glow of nostalgia. Cuts like “Come Back To Me” and “Sunny” have a swinging vibe and screaming brass the recalls nothing so much as New Orleans jazz. The album overall, however, has a reflective, meditative quality. The lyrical themes are on the passing of time and of the inevitability of change.

“All I Need Is The Girl”, “Indian Summer” and “Yellow Days” all have running times just under five minutes, much longer than standard pop duration.

“Sunny” would later be record by Boney M, and was written by Bobby Hebb in the two days after November 22nd 1963 – not only the day of JFK’s assassination but also his own brother’s murder. This is one of Sinatra’s more successful covers of a pop hit, and one in which (unlike Mrs Robinson or Both Sides Now) he makes the song his own, rather than a novelty.

Watertown (1970)

“Interesting” can be a damning word applied to any art. In pop culture, it can signify a kiss of death; the moment when something is no longer appreciated or enjoyed for its own sake but for some ulterior motive. I mean no disrespect to describe “Watertown” and one of the most interesting albums in Sinatra’s career, as well as the most mixed.

A song cycle written with members of the Four Seasons, along with the much more consistently successful Antonio Carlos Jobim collaborations, it marks probably the biggest departure from the Tin Pan Alley/Broadway songwriters mostly performed by Sinatra. 400,000 copies were pressed at the time of release; only 35,000 sold. The songs follow a man in the eponymous New Jersey town who has been abandoned by his wife to look after their children.

Watertown’s lyrics contain their share of embarrassing couplets: “Sitting in a coffee shop with cheesecake and some apple pie/She reaches out across the table looks at me and quietly says good-bye”, for instance, from “Goodbye (She Softly Says)”. Cole Porter this ain’t. Yet, there’s an emotional punch to many of the songs, and the pathos of Frank’s persona here (so at odds with the popular image of the ring-a-ding-ding swinger) is perhaps the most likely successor to lovelorn crooner of “In the Wee Small Hours.” Sometimes the sentiment teeters on the edge of treacle, but somehow stays on the right side, and on “What’s Now is Now” and “Michael and Peter” achieves a solemn dignity.

Those familiar with Scott Walker’s late 60s albums may find it easiest to think of Watertown as not dissimilar to Scott 4 – containing some sublime moments, but much more dated than, say Scott 3. Like many attempts to be up-to-the-minute, the result doesn’t date as well as when the singer just sings their songs.

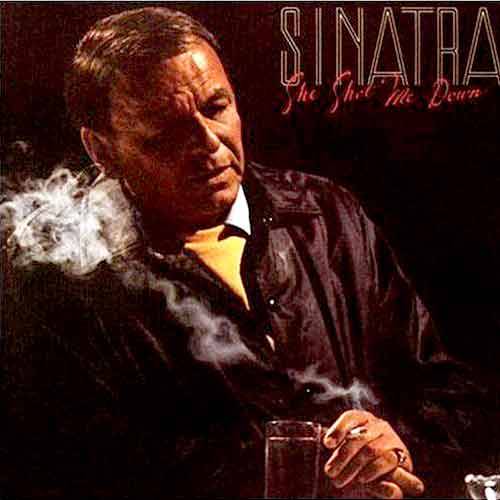

She Shot Me Down (1981)

By this time, notwithstanding his stadium success and the three megahits, in terms of album sales Sinatra had fallen off the charts; this didn’t make the British charts at all, and missed the Top 50 in the US. Sinatraologist (Sinatraician? Sinatraian?) Will Friedwald, in his magnum opus Sinatra! The Song Is You: A Singer’s Art, describes this as “the album that got away”, a hat tip to the majestic closing medley of “The Gal That Got Away” and “It Never Entered My Mind.” This is the Frank of “In The Wee Small Hours”, facing up to mortality and the passing time. This not just a medley, but a reprise, and an almost unbearably poignant one.

The title track is perhaps now better known in daughter Nancy’s version, which is on the Kill Bill soundtrack. This version is less stark, less stylised, and more emotionally true. Sinatra’s late works are, amongst other things, testament to the virtue of growing old gracefully; not for him the lame attempts by various rockers to present themselves as essentially unchanged over half-a-century. The pleasures of Sinatra after fifty differ from those of his golden years, but they are in their own way as rich, as rewarding, as evocative of a life lived in the full.

I really enjoyed all these. But then, if I’m honest, I much prefer Fat Elvis to the ‘cool’ Sun records stuff and find that Dylan’s later output speaks to me more than most of the 60s material, great as that is… Incidentally, Mark Steyn says that Dylan became quite friendly with Sinatra in his last years, and was constantly pestering him to record an album of Hank Williams songs: we can only imagine what that might have been like.

It would have been an interesting companion piece to the Dylan Christmas album.