Mahlerman stands well back and attempts to grasp the full scale of J S Bach’s achievements…

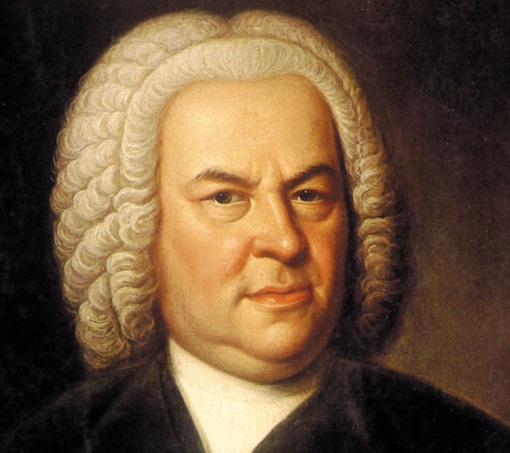

There is something mythical about Johann Sebastian Bach – for how else can we account for his superhuman mastery of form and substance? Beethoven alone bears comparison, but we are always aware of the struggle and effort, as if the music were hewn out of a rock-face (except perhaps in the late quartets). With JSB the hand never falters, there is no slackening of grip, and the faultless perfection of utterance follows quite naturally, as the dawn follows the darkest night. Is it as a result of this flawlessness that ubiquity, at least in our own age, should follow? After all, Bach is everywhere…..isn’t he? Can you live through a week without hearing his music – or a version of it? It is all over popular music, particularly the Beatles; jazz borrows without shame, or acknowledgement; when something bad happens, usually in America, if it is not to Bach they turn, it is to the next composer in the alphabet, Barber; and we lack the space here to cite the close-to 800 examples since 1931 in the cinema, on television – or just selling us stuff – like wooden mobile ‘phones.

The Touchwood SH-08C by NTT Docomo, in case you were wondering. Oh, the music? The last movement of the Cantata Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben BWV 147, better known here as ‘Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring’.

In 1722 Johann Sebastian Bach applied for the precentorship of Leipzig; he was 38, and although he was third choice, he accepted the post in the following year. The remuneration was derisory, the living conditions cold and damp, and his duties were legion – writing music for four churches was just the start. His other tasks as Cantor comprised teaching music and Latin in the Thomasschule, playing the organ when required, and training and directing musicians to play and sing. He had been living as a widower with his surviving four children, but had recently married his second wife Anna, who eventually produced a further thirteen. To put it mildly, life must have been difficult.

But as so often with creative artists in extremis, some of the greatest music ever written started to flow from his quill. From this period, probably after 1730, came the Flute Sonata in E flat major, BWV 1031. The German pianist Wilhelm Kempff made a number of Bach transcriptions, and here is the sublime Siciliano second movement from BWV 1031, played by probably the Bach pianist of our day, the Canadian Angela Hewitt. Perfect speed, perfect touch – I can’t hear this piece, played well, without thinking that perhaps there is a God, after all.

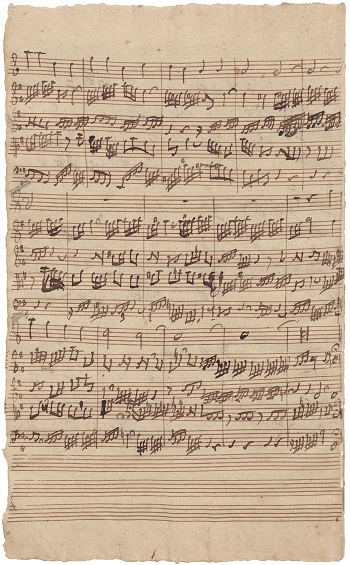

As I suggested last year in a post on the year 1685, the volume of compositions Bach produced beggars belief – even if you discount the work-load described above. Some bright spark has worked out that if a copyist (just copying, not composing) sat down to inscribe all of Bach’s music, including all the part-writing undertaken by the composer, it would take 70 years – and Bach died age 65. It took almost 50 years for a team to complete the project of publishing all his music. And against this backdrop it is worth reminding ourselves that almost everything he wrote was note-perfect in every detail [see below].

It is as if none of the weights and measures by which we estimate lesser men, can be applied to this amazing Lutheran: he is just too big, he bursts the bonds of judgement. And, for what it is worth, there is not a single composer since Bach last drew breath in 1750, who actually or theoretically does not seek to emulate him. Think of a composer, Google him, and when the subject of Bach comes up, as it always does, a hat will be removed, and eyes will be lowered. Michelangelo, Aristotle, Shakespeare…..Bach. That looks about right to me.

The six Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin, written around 1730, are technically, intellectually and emotionally the Mount Everest of violin playing, and buried away in their vastness is perhaps the single greatest challenge for a fiddler, the great Chaconne in D minor from the Second Partita. But even this great piece, surrounded as it is by others with a similar claim to our attention, is possessed of the same modesty that permeates all of Bach’s output. He never strains to catch our ear: the music is just there. And if you need an example of how well it travels across the years, listen to this version for Mandolin of the Presto final movement of the Sonata in G minor BWV 1001, played by the Californian multi-instrumentalist Chris Thile. With playing of such brilliance and passion, I thought he must be in front of an audience but no, when I leapt to my feet at the end, I was alone.

At the end of each of his cantata scores, Bach appended the initials SDG, Soli Deo Gloria. For this devout, hard working musician, the aim and final end of all music was ‘to the Glory of God alone‘ He sought no more than this, even when his fame began to spread in provincial Germany. His life as a jobbing musician continued, and he discovered that he had miraculously taught himself the fusion of mathematics and poetry.

The chorale preludes strike to the very core of Bach’s belief. They fall into four main groups, and among the Schubler Preludes is the rather wonderful Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme BWV 645 Wake, Awake for Night is Passing. It is played here by the Dutch master Ton Koopman, who plays the organ of Saint Mary Cathedral in Freiberg, Saxony, not far from where the music was composed.

Is it possible to think about Bach’s Goldberg Variations without thinking about the Canadian virtuoso Glenn Gould? For me it is not. Since his death over thirty years ago, aged just 50, opinions on his playing are as polorized as they ever were. The personal eccenricities have become the stuff of legend; his fondness for gamine Petula Clarke and his detestation of the Beatles’ music; his latter perchant for drug-cocktails of Valium, Barbiturates, Benzodiazepines etc; singing Mahler to elephants; wearing a thick overcoat, gloves and a cap most of the time – even in Florida, and sometimes when playing piano; and the weird, atonal humming-along to his own playing. And then, just when you think he might be an idiot savant (which perhaps he was), and you are about to ring for the men in white coats, you hear again that extraordinary first recording from 1955, when he was just 23, of BWV 988, the aria and thirty variations that made his name overnight. The speeds are dangerously fast, but……the performance is so imbued with life and vigor, that the listener feels that the pianist is discovering the piece as he goes along – even composing the piece as he goes along which, in a way, he was. As the great Hungarian conductor George Szell once remarked ‘That nut is a genius’ – this from a man not given to compliments of any kind.

I will be returning to Gould and other pianistic ‘nuts’ later in the year but, to end today, less than 2 minutes of stupefying brilliance, recorded a year before he died, playing the last movement Gigue from the Partita No 4 BWV 828. George Bush had ‘Wow’ on the teleprompter, but I don’t need a teleprompter – Wow!

Wonderful stuff.

Hear hear. As I told Mahlerman off-blog, I saw Angela Hewitt in Bristol (playing Chopin) and she was sublime.

Just in time for Bach’s 329th birthday, Mahlerman has given us a wonderful look into this profound and amazing composer. Every composer that followed Bach had to come to grips with with his music and his influence is everywhere. A good test of a composer is how well his music can be transferred to different instruments. Unlike other composers, Bach works on everything from the mandolin to the glass harp to the banjo. Thanks and happy birthday Sebastian.

Mike Lawrence

And perhaps I should mention to Dabblers that by clicking on Michael Lawrence Films you will arrive at Mike’s website, at the top of which is his documentary film ‘Bach & Friends’. The reviews are pretty effusive, and I believe a copy of this DVD is winging across the Atlantic to me, as I tap these keys.