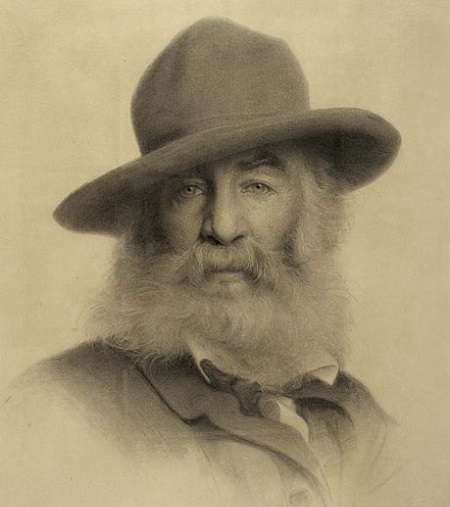

The poet Walt Whitman inspired not only writers but composers too. Here, Mahlerman introduces four exceptional pieces…

The great American humanist poet and essayist Walter ‘Walt’ Whitman believed that music had mystical, supernatural powers – in fact it was the only art-form he acknowledged to be greater than poetry, the ‘music’ of his own words. He, in turn, either by just being himself, or by the ceaseless flow of words, inspired a generation of composers to express their feelings in sound.

A more purely ‘musical’ poet than Whitman is hard to imagine, his innate musicality being present in almost everything he wrote. He called many of his poems ‘songs’, and developed his poetry in much the same way as a composer ‘develops’ and ‘recapitulates’ a symphonic movement. Here, read by the mysterious, pseudonymous Tom O’Bedlam are the first two parts of the 52 sections of one of them, the American epic Song of Myself, which so stunned me back in the 60’s when Whitman was, so to speak, ‘a la mode’. The poem is written in Whitman’s signature free verse style, and is quite possibly the most egotistical piece ever written dealing, for most of its great length, with the ideas and thoughts of the writer. But what thoughts!

After his adventures in Florida, where he probably contracted the syphilitic paralysis that would eventually kill him, the English composer Frederick Delius decided to marry the painter Jelka Rosen, and settle down in Grez-sur-Loing just outside Paris. In 1920 he started sketching the song-cycle that would become Songs of Farewell, the words having been selected by Jelka from Whitman’s Leaves of Grass Collection. By the mid 1920’s the disease had rendered the composer both blind and almost completely paralysed. The story of the arrival in 1928 of the twenty-two year old Eric Fenby as amanuensis to the composer is well enough known for me to pass over it here – but the plain truth is that without the selfless input of this unsophisticated Yorkshireman, Delius would never have finished some of the half-written masterworks that he had started, and set aside. The serene 5 part song-cycle for double-chorus and orchestra received its first performance in 1932. Here is the second song ‘I stand as on some mighty eagle’s beak’, played by the Thomas Beecham-trained Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the Ambrosian Singers. We can assume that the performance is authentic, as it is directed by none other than Eric Fenby. Indelible.

At the rise of Nazism and the Third Reich most artists and musicians in Germany either fled, or sat tight and towed the Party line. A few stayed to discreetly defy Hitler, and one of these was the Bavarian Karl Amadeus Hartmann who, though not a Jew, was debarred by the Nazis from all public activities because he favoured a liberal attitude to music. I got to know his music many years ago when I first heard his 4th and 6th symphonies (he composed eight). They seemed to me extraordinary, but writing these posts I simply could not imagine such uncompromisingly ‘tough’ music being suitable for a Lazy Sunday – nor is it, any of it. Hartmann has been called by some, the greatest German symphonist since Brahms, and I cannot take serious issue with that statement, even when I consider that his music is hardly ever played, particularly in England. His Symphony No 1, carrying the curious sub-title Versuch eines Requiems (Attempt at a Requiem), had a twenty-year gestation period, six years buried in a Bavarian mountainside to protect the score from Allied bombardment, and another five years of ‘denazification’, being finally published in 1956. It is the only one of the cycle that uses the human voice, and that voice expresses, in very free translations, the words of several Walt Whitman poems and, together with some often barbaric orchestral music, it comments rather clearly on the physical and spiritual devastation that remained after the crushing of the Nazi Regime. Here the amazing opening section, with Whitman’s words sung by the great German mezzo Doris Soffel.

The Symphony No 1 (Sea) by the Gloucester born modalist Ralph Vaughan Williams is beloved by choral societies but, it seems, few others. Admirers of the mature RVW give it a wide berth, but it should be said that although the composer was still in his 30’s when he wrote it, there are some magnificent effects in the piece, not least the words taken from Books 13, 16 and 19 of Walt Whitman’s epic Leaves of Grass, and sung by soprano and baritone soloists plus a large choir and orchestra, augmented by an organ. It is his biggest and longest symphony, lasting well over an hour – and sometimes it feels longer, but tucked away in the bombast and vastness of the score is, for me, one of the composer’s finest creations, the grave beauty of the second movement Sea Drift: On the Beach at Night, Alone, a magical seascape tone-poem if there ever was one.

And then there is Hindemith’s setting of Whitman’s “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d”, Whitman’s moving elegy for Lincoln.

Thank you for another very interesting piece.

My favourite Whitman-inspired piece is Bernstein’s setting of “To What You Said” in his vastly underrated “Songfest”: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_oZV774_k98

I shall, as the kids would say, “check out” the Hartmann.

Quite so Steerforth – Songfest is hardly ever performed and yet contains not just the wonderful number you mentioned (which has shades of ‘One Hand, One Heart’ from West Side Story, another marvel almost never heard), but at least four others. I did shortlist ‘To What You Said’ for inclusion (along with “lilacs’ Denkof – thankyou), and about six others, but felt, in the end, that Hartmann needed the exposure he rarely seems to get.

We seem to have lost some comments due to technical mysteries – apologies for that.

(Another brilliant topic, MM!)