An audio-visual treat for you this Sunday, as Mahlerman brings you three pieces of music inspired by great paintings…

Musical inspiration is, like mercury, almost impossible to grasp. It can arrive, as many believe it did to a certain WA Mozart, in a ‘lightbulb moment’ as if from God, and the fortunate recipient just has to inscribe it. But more often the muse is stirred by emotion or perhaps another work of art, and in these posts over the years we have enjoyed (I hope!) many of them: the ‘music’ of Shakespeare’s words; the wrath or love of God – or a God; Nature, Birdsong and The Sea or, more simply, Love and Death. Today we look at some painted works of art that either inspired composers or, at the very least, got them started.

Arezzo is a small city in the centre of Italy near Florence and was, most recently, the backdrop for Roberto Benigni’s touching film Life is Beautiful. The city is blessed with more than a dozen Gothic and Romanesque churches, and behind the austere (unfinished) frontage of one of them, the Basilica of San Francesco, resides one of the glories of the early Renaissance, the sequence of frescoes The Legend of the True Cross by the Tuscan mathematician and painter Piero della Francesca [detail above]. Dates are uncertain, but work on the series probably began around 1448, the final depiction of the Annunciation being completed about 20 years later.

Regular Dabblers will know that I have a pronounced weakness for the vastly underrated Czech composer Bohuslav Martinu, for which I offer no apology – and it was on a trip to Italy in 1955 that this Bohemian-Moravian master happened upon the small town of della Francesca’s birth (and death) Sansepulcro, travelling on to see the frescoes in nearby Arezzo. The effect upon the composer was immediate and profound, and I can do no better here, than quote the words of Brian Large, the composer’s biographer: ‘Martinu found the substance of all he wanted to put into music, the peace and colours of nature, the simplicity of form, the philosophy of acceptance and resignation’. Martinu did not attempt to ‘describe’ the sequence in sound, rather, through a process of distillation, he sought to express the extraordinary serenity the artist communicates through his geometry of form and use of colour, describing thus ‘a solemn, frozen silence and opaque coloured atmosphere, which contains strange, peaceful, yet moving poetry’.

The 20 minute suite Les Fresques de Piero della Francesca is cast in three movements, and the second movement Adagio is nominally Constantine’s Dream [see detail above], in which an angel assures the future emperor he will conquer the rival Roman leader Maxentius by following the sign of the cross. It is played to the manner born in this short video by the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by the great Jewish Bohemian Karel Ancerl, whose image appears in the second half.

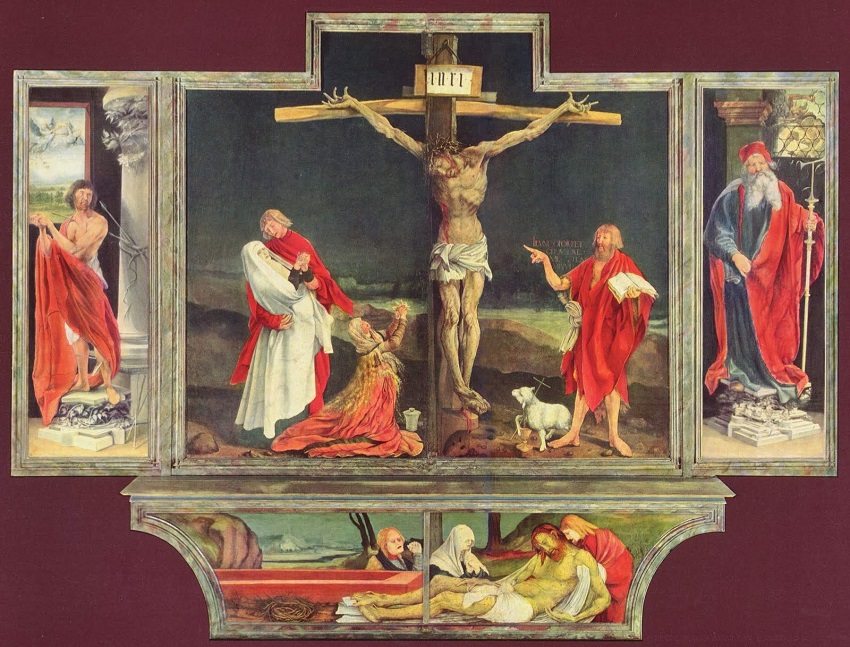

Details of the lives of artists working in the 15th Century are usually exiguous and often unreliable, and at around the same time as Piero was completing the True Cross in Italy, a child was born to unknown parents, probably near Frankfurt in Germany. This was Matthias Grunewald who would, in his late thirties, paint and sculpt one of the great masterpieces of religious art, the Isenheim Altarpiece [below], now residing in Colmar, Alsace – a German ‘Sistine Chapel’ sitting in France. The altarpiece was made for an Antonite monastery near Colmar that treated the gangrenous disease ergotism, then known as ‘St Anthony’s Fire’, a condition brought on by eating rye bread infected by a parasitic fungus…and this goes some way to explaining the frightening appearance of Christ’s flesh on the altarpiece. We have become used to the sanitization of religious imagery through the pressing desire for the artist to show us what he thinks, even what he believes. No such ‘expression’ was required in the middle ages; most of the flock were poor and illiterate, and art of this kind simply told the story, in graphic terms, of Christ’s torture, and foul death, the greenish corpse even oozing bodily fluids.

In 1932, the publisher to the great German iconoclast composer Paul Hindemith suggested that he might like to consider an opera based upon the life of Grunewald, and although the composer was at first lukewarm on the subject, his enthusiasm was ignited a year later at the very moment the Nazis came to power – ‘His exploits shattered my very soul’ he was to say much later. Hindemith’s wife was Jewish and he had always been treated with suspicion, at best, by the Party, along with other politically liberal Germans. As the work took shape in his mind (and on the page), this tense relationship deteriorated to the point where his music was branded as ‘decadent’, and performances were banned – but before he could complete the opera, he drew from the material already composed a marvellous three-movement ‘symphony’ Mathis der Maler (Mathis the Painter), which received a triumphant premiere in 1934, with Wilhelm Furtwangler conducting the Berlin Philharmonic. We hear the second movement Grablegung (Entombment) on this recording of the same orchestra, conducted by the composer.

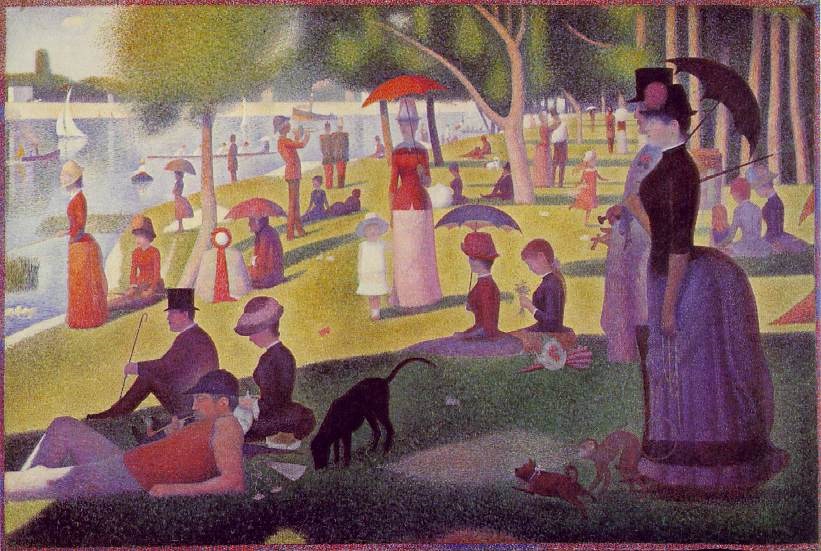

The life of the Neo-Expressionist painter Georges-Pierre Seurat is also cloaked in mystery but for a particular reason; he preferred it that way. In his brief life (he lived, like Franz Schubert, for just 31 years), mostly in Paris, he was able to live in quietude, on his own terms because, unusually for an artist, he came from a background of wealth and comfort. His famously withdrawn manner was either inherited from his father or, more likely, was learned behaviour, as Antoine-Christophe would spend just one day a week with his family, a Tuesday; for the other six-sevenths of his life he would retire to a family villa outside Paris to tend his garden. As a teenager Georges attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts but took issue with the techniques of impressionism that dominated at that time (1878), and began to develop a method of applying oil paint to a white canvas that would, eventually, make his name. He called it chromoluminarism, a bit of a mouthful in any language; we know it today as pointillism – the application of small, tightly-packed ‘dots’ of pure colour (unmixed) that, viewed from a distance, meld together by an optical ‘trick’ to give a magical ‘illuminated’ effect. His first major painting in this style Bathers at Asnieres can be seen at our own National Gallery – and a five minute stroll from the National to the Courtauld on Waterloo Bridge will gift you the opportunity to see the only known image of perhaps Seurat’s biggest secret – the working class woman Madeleine Knobloch in Young Woman Powdering Herself. Madeleine bore him two children, but was unknown to any of his friends, or to his mother, until just two days before the painter’s death.

To see Seurat’s greatest masterpiece you will need to visit the Art Institute of Chicago, for there hangs the 2 x 3 metre maze of dots A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of Grande Jatte [above], the picture that defined him – and has inspired countless artists and writers since, among them the librettist James Elliot Lapine and composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim who, in 1982, began work on the musical drama that became Sunday in the Park with George. Not so much a ‘musical’ as a complex meditation on the creative process and, I suppose, life in general. After all, a brief examination of Seurat’s short life would surely lead you to the conclusion that ‘They’ll never make a musical out of that’ – but out of the slim strands of fact Sondheim, no stranger to magical realism, wove a wonderful score, adding his own wry lyrics to the pointillistic, almost oriental music. Subtle clues are everywhere – his girlfriend is called Dot, and note the trumpet player at left-centre of the picture, and hear him anew in the mavellous anthemic number ‘Sunday’ that ends both the first and second act of this great musical drama – in this recording the trumpet part, the very last note, is taken by a french horn. The parts of George and Dot were indelibly etched in this New York performance by two singing-actors often linked to Sondheim, the high tenor Mandy Patinkin and the unforgettable Bernadette Peters.

Bathers at Asnieres is one of my favourite paintings and I often pop in to feast my eyes on it when near the National Gallery. I’ve never heard any of ‘Sunday’ before – thanks MM – terrific theme, yet again.