There was much more to Thomas Hardy than pessimism, as Edward Thomas observed…

Edward Thomas knew English poetry backwards and forwards. Not surprisingly, therefore, his comments on particular poets are very perceptive. When it comes to the poetry of Thomas Hardy, Thomas (as is the case with anyone who reads the poems) is bound to remark upon Hardy’s pessimism. Who wouldn’t? Consider, for instance, “Hap,” the fourth poem in Hardy’s first collection. With its references to “Crass Casualty,” “dicing Time,” and “purblind Doomsters,” the poem establishes a theme that occurs again and again in Hardy’s poetry.

In his review of Hardy’s 1909 collection Time’s Laughingstocks and Other Poems, Thomas memorably acknowledges the conventional wisdom about Hardy’s pessimism: “The book contains ninety-nine reasons for not living.” (Despite his melancholy, Thomas did have a sly and dry sense of humor. One can see why he and Robert Frost got along so well together.) But Thomas wisely recognizes that there is much more to Hardy:

The book contains ninety-nine reasons for not living. Yet it is not a book of despair. It is a book of sincerity . . . Mr. Hardy looks at things as they are, and what is still more notable he does not adopt the genial consolation that they might be worse, that in spite of them many are happy, and that the unhappy live on and will not die. His worst tragedies are due as much to transient and alterable custom as to the nature of things. He sees this, and he makes us see it. The moan of his verse rouses an echo that is as brave as a trumpet.

Edward Thomas, review of Time’s Laughingstocks and Other Poems, in The Daily Chronicle (December 7 1909), reprinted in Edna Longley (editor), A Language Not To Be Betrayed: Selected Prose of Edward Thomas (1981).

Hardy’s poem “Going and Staying” is, I think, a good illustration of the point that Thomas makes. It first appeared in the inaugural issue of The London Mercury (edited by J. C. Squire, the bane of T. S. Eliot and other “Modernists”) in November of 1919 as follows:

Going and Staying

The moving sun-shapes on the spray,

The sparkles where the brook was flowing,

Pink faces, plightings, moonlit May,

These were the things we wished would stay;

But they were going.Seasons of blankness as of snow,

The silent bleed of a world decaying,

The moan of multitudes in woe,

These were the things we wished would go;

But they were staying.

One would think that, after making these jolly observations, Hardy had said enough. But he could not leave well enough alone. Hence, when the poem was published in book form in 1922, Hardy (a clever lad at the age of 82) added a third stanza:

Then we looked closelier at Time,

And saw his ghostly arms revolving

To sweep off woeful things with prime,

Things sinister with things sublime

Alike dissolving.Thomas Hardy, Late Lyrics and Earlier (1922).

Now, whether this third stanza is calculated to make us feel better or worse, I cannot say. I also cannot say whether it makes this particular reader feel better or worse. But one thing is certain: it is classic Hardy.

I really do love Hardy, despite being rather intolerant of miserabilism. The more one reads of his life the more one realises he was like many a grumpy farmer: ever complaining but with a twinkle in his eye.

His poems are, true, generally melancholy and pessimistic; but one gets the impression that the sap can’t be stopped from bubbling up. The lyricism and the sense battle it out and who’s to say which wins?

Gaw: Very well put. I completely agree with your assessment of Hardy and his poetry, particularly your observation that he had “a twinkle in his eye.” Numerous accounts of those who met Hardy are collected in Thomas Hardy Remembered (Ashgate 2007), which was edited by Martin Ray. The accounts are remarkably consistent: he was a guarded, but a charming and diffident, man. Here’s a lovely fact: he and T. E. Lawrence seem to have gotten along famously with each other.

Another thing that counterbalances his pessimism is his remarkable empathy with, and compassion for, his fellow human beings (as individuals, not in the abstract). He may have been pessimistic, but he was not a misanthrope. And this comes through very clearly in his poetry.

Thank you very much for your thoughts.

Thanks for the recommendation, Stephen. However, Ray’s book is £50+ on Amazon. I shall have to drop some Christmas present hints…

Lovely to learn some more about Hardy. I grew up in the West Country and we studied Hardy’s poetry at school – he’s been something of a fixture in my life. So special thanks for today’s post and comment.

Gaw: you are welcome. My pleasure. As for the price of Thomas Hardy Remembered: yes, I agree, very dear (one of those academic imprints). Being a Hardy devotee, I had to bite the bullet.

Thomas Hardy and T.E. Lawrence did indeed become close in the last few years of Hardy’s life, when Lawrence would slip out of the Tank Corps Camp at Bovington, Dorset and bike over to Max Gate for afternoon tea. Apparently, TEL was one of a tiny handful of guests tolerated by Hardy’s ferocious Caesar terrier, Wessex, who exerted a reign of terror in the household — both John Galsworthy and the eminent surgeon Sir Frederick Treeves had their trousers ripped to shreds and Cynthia Asquith describes how the dog “contested” every morsel of food she raised to her mouth.

In a letter to Robert Graves Lawrence wrote a rather beautiful account of Hardy at the end of his days — “so pale, so quiet, so refined into an essence”:

There is an unbelievable dignity and ripeness about Hardy: he is waiting so tranquilly for death, without a desire or ambition left in his spirit, as far as I can feel it: and yet he entertains so many illusions, and hopes for the world, things which I, in my disillusioned middle-age, feel to be illusory. They used to call this man a pessimist. While really he is full of fancy expectations.

Then he is so far-away. Napoleon is a real man to him, and the country of Dorsetshire echoes the name everywhere in Hardy’s ears. He lives in his period, and thinks of it as the great war: whereas to me that nightmare through the fringe of which I passed has dwarfed all memories of other wars, so that they seem trivial, half-amusing incidents.

Also he is so assured. I said something a little reflecting on Homer: and he took me up at once, saying that it was not to be despised: that it was very kin to [Scott’s] Marmion … saying this not with a grimace, as I would say it, a feeling smart and original and modern, but with the most tolerant kindness in the world. Conceive a man to whom Homer and Scott are companions: who feels easy in such presences … He feels interest in everyone, and veneration for no-one. I’ve not found in him any bowing-down, moral or material or spiritual.

Yet any little man finds this detachment of Hardy’s a vast compliment and comfort. He takes me as soberly as he would take John Milton … considers me as carefully, is as interested in me: for … Hardy has no preferences: and I think no dislikes, except for the people who betray his confidence and publish him to the world.

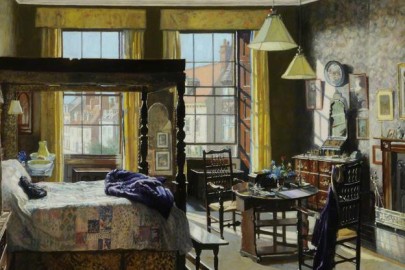

Perhaps that’s partly the secret of that strange house hidden behind its thicket of trees … Anyone who does pierce through is accepted by Hardy and Mrs. Hardy as one whom they have known always and from whom nothing need be hid. Max Gate is a place apart: and I feel it all the more poignantly for the contrast of life in this squalid camp. It is strange to pass from the noise and thoughtlessness of sergeants’ company into a peace so secure that in it not even Mrs. Hardy’s tea-cups rattle on the tray: and from a barrack of hollow senseless bustle to the cheerful calm of T.H. thinking aloud about life … If I were in his place I would never wish to die: or even to wish other men dead. The peace which passeth all understanding: — but it can be felt, and is nearly unbearable.

jonathan law: thank you very much for the Lawrence letter — it is wonderful. I have seen excerpts from it before, but never the whole thing.

I think that Hardy was indeed quite fond of Lawrence. In Thomas Hardy Remembered, there is an account by the actress Gertrude Bulger about her last visit with Hardy. In it, she describes talking with him about Lawrence. Hardy said of Lawrence: “He is a very great man.”

A side-note regarding “Wessex”: as you may know, Edmund Blunden was another of the guests who was tolerated by him.

Thank you again.

If one can believe Henry Adams, Swinburne was able to recite whole plays backwards (I suppose forwards is a given then).

I do not know Hardy in either direction. If challenged to recite one of his poems through, I would probably have to fall back on “In the Time of Breaking of Nations”, unless–as I can imagine happening–I slipped and recited Houseman’s “Epitaph on an Army of Mercenary Soldiers.”

Yet the poetry seems to me at its best when the pessimism is subordinated, as in “Ancient to Ancients” or controlled as in “During Wind and Rain.” He had something of a tendency to dogmatize his pessimism, which made for stretches of nicely worked out but not very interesting poems.

George: I understand your feelings. But, given that Hardy published more than 900 poems (947 according to James Gibson’s 1976 edition of The Complete Poems — I didn’t count them; thankfully Gibson numbered them!), which inevitably leads to some repetition.

I admit my bias towards Hardy (he is probably my favorite poet, with Larkin and Edward Thomas in close running), but I agree with Larkin’s assessment of Hardy’s output: “may I trumpet the assurance that one reader at least would not wish Hardy’s Collected Poems a single page shorter, and regards it as many times over the best body of poetic work this century has so far to show.” Philip Larkin, “Wanted: Good Hardy Critic,” Required Writing (1982), page 174.

Mind you, I hope I don’t sound argumentative, and I am not trying to bludgeon you into submission! And I recognize that your point of view on Hardy is shared by many. So I am not claiming to be “right.” Who could be? Poetry is a matter of emotion, affinity, and affection when it comes to our favorites, isn’t it?

I greatly appreciate hearing your thoughts.

Bad editing on my part: please omit “,given that” in the second sentence of my reply.

Well,I for one think it’s better without the last stanza, but I find it fascinating that in old age he felt the need to add something – to take the edge off the undiluted despair, maybe.

thanks for the poetry moment – I don’t get many!

Ali B

Ali B: you are welcome. My pleasure.

I suspect you are right about his reasons for adding the third stanza. He was always sensitive about accusations that he was a pessimist, and he defended himself against the charge in a few of the prefaces to his individual collections of poetry.

For instance, in the preface to Winter Words (his final collection, published in 1928 after his death), he writes: “My last volume of poems was pronounced wholly gloomy and pessimistic by reviewers — even by some of the more able class. . . . As labels stick, I foresee readily enough that the same perennial inscription will be set on the following pages, and therefore take no trouble to argue on the proceeding, notwithstanding the surprises to which I could treat my critics by uncovering a place here and there to them in the volume.”