Shakespeare’s cultural influence extends far beyond literature. As Mahlerman explains, the Bard has influenced musicians and composers across the world…

The term, first invoked by G B Shaw at the birth of the 20th Century to indicate idolisation or, at the very least, an ‘excessive admiration’ for our greatest poet and playwright, probably began to gain some traction during the lifetime of the ‘Bard of Avon’, but my own awareness of it, as a callow 18 year old, began in 1964 when Stratford-upon-Avon, near where I then lived, went completely bonkers celebrating the great man’s four hundredth birthday. The townsfolk, normally rather modest souls, quietly proud of their most famous son but secretly resenting the almost constant influx of coaches and cars carrying the faithful, were transformed into a howling mob of rabid rapaciousness, intent on relieving the visitors of their lucre in double-quick time, in exchange for a few worthless baubles of dreck for their mantles and display cabinets; display cabinets were very big in the mid 1960’s.

The fever for Shakespeare is of course worldwide and not confined within the armies of tourists swarming across Warwickshire. The ‘music’ of his words has influenced and inspired writers and composers, the latter group particularly throughout the late 19th Century and beyond. Today we ‘lend an ear’ to a few of these…..

Like many of the compositions of the English (tho’ from Italian-Jewish parentage) composer Gerald Finzi, the opus 18 song cycle Let Us Garlands Bring had a long gestation period – from 1929 to 1942 in fact. And of the set of five, the third song Fear No More the Heat o’ the Sun is, by most reckoning considered the finest, and one of the greatest songs in the English canon of the last century. From Act IV of Cymbeline the stately and dignified verse muses, for most of its length, on the appeal of life’s sunset and the end of the travails of life, and the fact that we all must ‘As Chimney-Sweepers come to dust’. Unusually, the rocking pulse of the piece is stilled before the last verse becomes a sort-of recitative, leading us to the devastating conclusion of ‘Quiet consumation have; and renowned be thy grave’. The performance here, by the bass-baritone Bryn Terfel and pianist Malcolm Martineau seems to me to be as near-definative as makes no difference.

Over the last few hundred years there have been very few composers whose love for Shakespeare’s verse has not resulted in something memorable. It is perhaps not too surprising that Mozart was unmoved, but I would have imagined that Beethoven could have reached the essence of him but, for reasons we will never know, stayed clear. In the 19th Century both Verdi and Tchaikovsky penned masterworks and in France, Hector Berlioz was ‘..struck like a thunderbolt’ and began a life-long love affair. Straddling the centuries were Sibelius and Prokofiev and, closer to our own time both Britten and William Walton left enduring endorsements of their affection. And let us not forget Leonard Berstein’s West Side Story.

In the thirty-odd volumes of The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians is this remark about Felix Mendelssohn’s magical overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream by George Grove: ‘….the greatest marvel of early maturity that the world has ever seen in music’. Felix was 17 years old. He went on much later to complete the task with further incidental music both vocal and instrumental, and this staggering Scherzo was one of this collection, music ‘light as thistle-down’.

Olivier’s fine but rather arch version of Hamlet (1948) was, to my eyes and ears completely eclipsed in 1964 with the release of Hamlet by the Russian Grigori Kozintsev, in a translation by Boris Pasternak, and a marvellous score by Kozintsev’s friend Dimitri Shostakovich. The film was recognised as an artistic triumph around the world (and by Olivier, no less), and it is something of a mystery that it is not better known here than it is. Shostakovich’s score, written at around the time of his revision of the long-supressed opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, contains the dissonance and dark, brooding quality of that infamous work. That darkness can be heard here in the famous scene where the Ghost urges Hamlet ‘If thou didst ever thy dear father love’ to take revenge for his ‘…most unnatural murder’

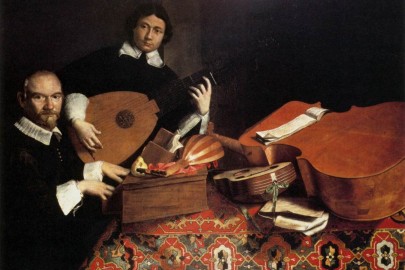

William Shakespeare loved music, squeezing it into his plays whenever he could – and he went further, saying that a man who doesn’t like music isn’t trustworthy, that such a man is capable of a base act, or murder. How the Bard would have loved to have heard the pastoral poetry of The Lark Ascending, the stained-glass beauty of the Tallis Fantasia or, better still, the simple melodic appeal of the Serenade to Music by Ralf Vaughan Williams. Written to a commission by Henry Wood to celebrate his Jubilee concert, RVW alighted upon a scene between Jessica and Lorenzo in The Merchant of Venice, producing one of his most beautiful and enduring works. The Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninov, no stranger to beautiful themes, was present in London at the first performance and was discovered in tears at the closing pages, which we can hear in this performance by Sir Adrian Boult conducting the LPO plus soloists and chorus.

The VW Serenade is a sublime piece, so I can understand Rachmaninov’s reaction.

loved the serenade and the hamlet – very dark and atmospheric indeed!

Im off to drive through stratford right now in fact as the sky is blue, and there’s a good walk along the avon on the far side of town

I stepped briskly and nimbly through the early part of a lazy Sunday afternoon; coming briefly across Gerald Finzi: he nodded, smiled, moved on. Then young Felix Mendelssohn: precocious little sod, blocked my way for a while; begging for recognition; he got it; I suppose he’ll go far. I then turned down an alleyway, the sun was suddenly gone; then I remembered: this was a place avoided by locals. I half-stopped and prepared to turn back, but it was too late: he seemed to leap out of the slimy, moss-green brickwork and gave me a thunderous smack in the earhole, his accomplice kicked me in stomach. They were gone as suddenly as they came; they’d asked for nothing and took nothing. I was left in a state of shock and emotional turmoil; the sounds they made during the attack chilled the blood. The coppers caught them; their names: Grigori Kozintsev and Dmitri Shostakovich, two Russians. Well we know what they’re like – all darkness and brooding intensity. What happened to border controls? Anyway, when I came round, and it took some time, I can tell you, there she was: a dead-ringer for Michelle Pfeiffer, gazing longingly into my bloodshot mincers; she was singing:

How sweet the moonlight sleeps upon this bank!

Here will we sit, and let the sounds of music

Creep in our ears; soft stillness and the night

Become the stillness of sweet harmony

My vision was, by now, blurred; I could see eight Michelles and, sadly, eight hairy blokes, but all singing like angels. It was so beautiful; it could have been written by Ralph Vaughan Williams.

This comment has been nicked from the Mills and Boon back-catalogue of rejected scripts – filed under NTSTLOD (Never To See The Light of Day)

As always, great post MM.

Ha!

Brilliant, John

Don’t know what JH is on Recusant, but whatever it is I’d like some.

Thanks Recusant and MM.

The Kozintsev excerpt is astonishing: I had never come across it until this post; such is the breadth and depth of my ignorance. How I wish I’d discovered Shakespeare in my youth, but I suppose better late than never.

MM, I found your comments about Olivier’s 1948 film version interesting; it’s an observation about which I am unable to make an informed comment, but it does inspire me to seek out the film and the version from Kozintsev. Was Olivier an habitual or occasional over-actor? I don’t know, but I do know he could utterly beguile with a restraint and modesty seemingly bordering on non-acting (Does that make any sense?) Last week I dropped my wife at a primary school where she collected our granddaughter. The collection was delayed. I waited in the car and listened to sections from the soundtrack of Olivier’s 1944 film version of Henry V with William Walton’s masterly score. I sat with tears in my eyes, mesmerised by Shakespeare’s language and Olivier’s performance, or lack of it :

Now entertain conjecture of a time

When creeping murmur and the poring dark

Fills the wide vessel of the universe……….

……………………..

I’ll leave it there; I don’t think I can take any more at the moment.

Olivier was roundly scorned for his film roles yet always praised for his stage acting. Apparently he was no good at speeches either. I think one of the most famous lampoons of Olivier was Peter Seller’s great take on his mannered speech

http://youtu.be/zLEMncv140s