From Wordsworth to Auden, a surprising number of famous poems have been blighted – or sometimes, improved – by printing errors, as Jonathan Law reveals…

On a hazy day at the close of August Frank Key gave us his startling revisionist take on a well-known poem by Sylvia Plath:

In her mad poem ‘Daddy’, Sylvia Plath makes mention of “a bag full of God”. I have always taken this to be a misprint … I am as sure as eggs is eggs that what Plath originally wrote was “a bag full of Goo”. A slapdash printer made “Goo” into “God”, and the error has persisted for half a century …

I’m not enough of a Plath scholar to say whether Frank could be right, but the history of these things suggests that it’s far from impossible. Given Wilde’s dictum that “a poet can survive anything but a misprint”, you’d think that printers and publishers would take fierce pains to avoid even minor errata in poetry: but this just isn’t the case. If anything, radical, outrageous, sense-subverting typos are more common in verse than in the workaday medium of prose.

I suspect there might be two reasons for this. In the first place, many poems make their debut in tiny, no-budget magazines that can’t afford proof-readers and don’t send page proofs to the author; this is true even of new work by the Big Beasts of the poetry world. Errors introduced here are often perpetuated in later editions and can easily end up enshrined in the big posthumous Collected unless there is a thorough check of printed texts against MSS. Secondly, and rather more interestingly, there’s something about the language of poetry that makes it strangely pervious to error. In prose, any half-decent editor will query an incongruous word or a phrase that doesn’t seem to stack up in the ordinary way; some mistake surely. But in poetry, where odd collocations abound and everyday meanings get stretched and twisted like blu-tack? As long as a word passes spellcheck, then who’s to say that it’s (certainly) wrong? Editors with fidgety fingers need to remember the case of Richard Bentley, the great classical scholar who published his ‘corrected version’ of Paradise Lost in 1732; arguing that the blind poet had been let down by his scribes, Bentley expunged scores of sublime Miltonisms that troubled his 18th-century notions of sense and taste (obviously, the great Milton could never have written anything as illogical as “darkness visible” – what he wanted to say was “a transpicuous gloom”).

In the best poems, words are charged with a weird static and every stanza carries its tiny shock of delight. But if the language of poetry depends crucially upon surprise, then the word that slips into a poem by sheer fluke – through accident or inattention – will sometimes look and act as if it has a perfect right of abode. At times there may be a true serendipity – the word that was never meant bringing a rich strangeness or glamour. There’s a well-known example in Auden’s Journey to Iceland, which originally began:

And the traveller hopes: “Let me be far from any

Physician”; and the poets have names for the sea;

The citiless, the corroding, the sorrow

And North means to all: “Reject!”

However, when Auden received the galleys from Faber this had itself undergone a sea change: the second line now read

…and the ports have names for the sea

– a gift that the poet was happy to accept.

There’s a more dubious case in Wordsworth, in his otherwise not very interesting poem ‘To Miss Blackett, on Her First Ascent to the Summit of Helvellyn’. In the poem that he wrote in (probably) 1816 Wordsworth alluded to certain “choral fountains” that he imagined playing in certain caves in the mountains of the moon; come the collected edition of 1832, however, and these had become “coral fountains” – a freakish but not unappealing idea that fits well enough with the odd vein of fantasy in the piece. Very likely this originated as a mistake, but if so it’s one the poet decided to stick with in all subsequent editions appearing in his lifetime (Wordsworth was a fanatical reader of proofs, so it’s hard to believe that he simply missed it). Rather unimaginatively, all the great poet’s modern editors have opted to restore “choral” – the 1914 Oxford edition insisting sternly that “Wordsworth was not a writer of nonsense-verses” and opining that “coral fountains” is in any case a “vile phrase” (if anything, he should have written “fountains coralline”).

Something a bit similar happened in US editions of Yeats’s Collected Poems, which for many years printed this version of lines from his glorious poem Among School Children:

Plato thought nature but a spume that plays

Upon a ghostly paradigm of things;

Soldier Aristotle played the taws

Upon the bottom of a king of kings …

Miraculous stuff you might think, a signature piece of full-blown late period Yeats; but hold it right there – what Yeats actually wrote was “solider Aristotle” (solider, that is, than spumy old Plato). Having grown up with the ‘wrong’ version of this I can’t help preferring it: surely the line scans better and the epithet “soldier” is all the stronger for being unexpected (Aristotle was never himself a fighting man but certainly cheered on the exploits of his pupil, Alexander). Just possibly Yeats agreed: if he was aware of the error, then like Wordsworth he took no steps to put it right.

Prestigious collected editions seem oddly prone to this sort of thing. In terms of its typos and other minor errors, the most notorious Collected of modern times has to be the bestselling edition of Larkin’s poems published by Anthony Thwaite in 1988 (but don’t let that put you off: there are several important reasons why this book is better than either of the subsequent big Larkins). According to James Fenton, writing in the New York Times, one 12-line poem, ‘Long Sight in Age’, contains no less than three significant errors:

They say eyes clear with age,

As dew clarifies air

To sharpen evenings,

As if time put an edge

Round the last shape of things

To show them there;

The many-levelled trees,

The long soft tides of grass

Wrinkling away the gold

Wind-ridden waves—all these,

They say, come back into focus

As we grow old.

That is the poem as Thwaite prints it; but his own eyes were obviously far from clear. Larkin wrote “lost shape of things” not “last shape” and at the close of the piece there are no “waves” of any sort but rather weather vanes, glinting as they turn in the sun:

The long soft tides of grass

Wincing away, the gold

Wind-ridden vanes

The real surprise is how little any of this matters; Thwaite’s errors do nothing to detract from the chill beauty of Larkin’s poem or the coherence of its central conceit. “Last shape” brings the idea of mortality into a still more pitiless focus, and the lines about “wind-ridden waves” of grass seem finely characteristic of Larkin when he is working this lyrical-elegiac mode. As Fenton writes: “I can see it, the wind riding the grass in waves that seem to wrinkle. But it’s not Larkin.”

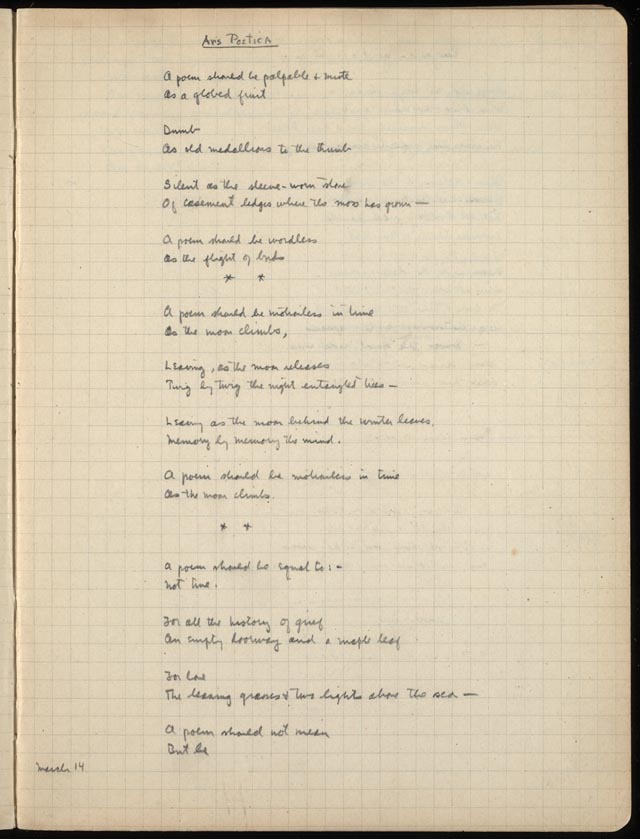

Sometimes, of course, a misprint will be more jarringly subversive of a writer’s intention. In the Collected Poems of Archibald MacLeish, for example, the editors somehow contrived to misprint two of the best-known lines in his very famous Ars Poetica:

A poem should be wordless

As the flight of birds.

Is it just the over-familiarity of this piece – cited ad nauseam in every discussion of modernist poetics – that gives me a sneaking fondness for the botched version?

A poem should be worldless

As the flight of birds.

That makes no sense at all, in context, and entirely subverts MacLeish’s insistence on the concrete, this-worldly nature of poetry (“A poem should be palpable and mute/ As a globed fruit” and so on). But all the same, that “worldless flight” is beguiling – a rush of the airiest Shelleyan romanticism where no one would look for it.

And there perhaps you have it. There’s something of the romantic sublime about a good misprint, something that makes it a little bit harder to think straightforwardly about the relation of word to world (or indeed, of goo to God).

fascinating reading Jonathan, what a great subject! It must be a nightmare being a poet and seeing some particularly important punctuation being mangled, thus changing the stress of a line.

Yes, but perhaps the greater nightmare, as Jonathan suggests, is how little it seems to matter to the effect and power of the poem if one of those agonised-over words is accidentally replaced.

Fascinating indeed – especially as I’d just noticed an oddity about the first line of Wallace Stevens’s Credences of Summer. I’d always read it as ‘Now is midsummer come and all fools slaughtered’ – but all versions I can find actually read ‘Now in midsummer come…’ That doesn’t make sense, does it – or am I just being thick?

Interpreting Stevens’s poetry is a mug’s game, but here are some tentative thoughts. Stevens took a walk nearly every day in Elizabeth Park in Hartford. Ducks were a feature of the park, and they make appearances in his poetry: “And one last look at the ducks is a look/At lucent children round her in a ring.” (“The Hermitage at the Center.”)

Thus, here is a guess (and only a guess) at why “Now in midsummer come and all fools slaughtered” makes sense. The full stanza reads:

Now in midsummer come and all fools slaughtered

And spring’s infuriations over and a long way

To the first autumnal inhalations, young broods

Are in the grass, the roses are heavy with a weight

Of fragrance, and the mind lays by its trouble.

Perhaps it is “young broods” [of ducks] that are “now in midsummer come” to Elizabeth Park. Alas, some of them have not survived (“all fools slaughtered”) since their birth earlier in the year, but others have made it through “spring’s infuriations.”

This is just a thought. And I am no doubt wrong. (I am also mindful that explication destroys poetry.) For instance, I sometimes think that “A Rabbit as King of the Ghosts” is about a rabbit that was devouring the bulbs in Stevens’s flower garden, a rabbit that Stevens’s mentions in a letter written in May of 1937.

Larkin would have winced away at the misprints in Thwaite’s edition, but they are pygmies compared to the one Larkin himself committed when, editing The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse, he unintentionally left out 18 lines of William Empson’s poem ‘Aubade’: oh bad indeed.

A favourite misprint, but critical rather than poetical:

Recalled by Alan Watkins here: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Short-Walk-Down-Fleet-Street/dp/0715631438

The household Collected Yeats, 1979, 24th printing, has “solider”. But “soldier” sounds familiar. Of course, the classic case is Shakespeare, where editors have had to make their guesses.

Thank you Mr Bleaney – an intriguing possibility…

Wouldn’t the Spectator be interested in such an interesting article as this?

I’m working on it.